While noted for their historical charm and timekeeping abilities, some of Montreal’s clocks are reputed to be haunted. Most of Montreal’s haunted clocks are located on St. James Street, an area associated with the extreme desecration of French colonial cemeteries by various financial corporations.

Welcome to the fifty-seventh installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog!

With over 350 documented ghost stories, Montreal is easily the most haunted city in Canada, if not all of North America. Haunted Montreal dedicates itself to researching these paranormal tales, and the Haunted Montreal Blog unveils a newly researched Montreal ghost story on the 13th of every month! This service is free and you can sign up to our mailing list (top, right-hand corner for desktops and at the bottom for mobile devices) if you wish to receive it every month on the 13th!

Haunted Montreal has suspended all public tours due to COVID-19 directives from government and health officials to keep our staff and clients safe. Please stay tuned to our website, blog and Facebook page for updates!

In the meantime, clients can enjoy reading the Haunted Montreal blog, which features over 50 local ghost stories, FOR FREE!

Our May blog explores the little-known story of mysterious mermaids seen swimming in the rivers surrounding Montreal Island. These strange creatures have been reported in the waters for thousands of years, far before Contact when the river was known as Kaniatarowanenneh and the island as Tiohtià:ke. Following colonization, French settlers were so upset with these creatures that they allegedly killed one, which they described as a “marine monster” in the nearby Richelieu River.

Haunted Research

Dating back to the pre-contact days when today’s Montreal Island was widely-known as Tiohtià:ke, a legend about strange monsters swimming in Kaniatarowanenneh, the big waterway, circulated among many First Nations. The dangerous aquatic creatures not only swam in the great river, but also its tributaries and other bodies of water.

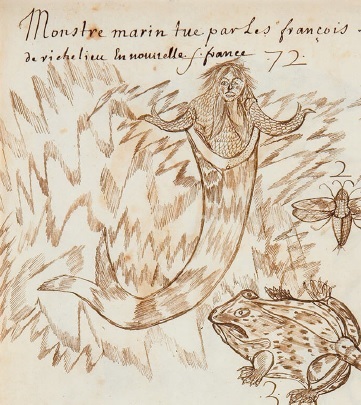

When the French colonized in the 1600s, they too encountered these mysterious creatures. Jesuit missionary Louis Nicolas created a Codex depicting a bizarre mermaid combining a fish tale with a human torso. The face appears rather feminine with long hair, but under the chin are fins or possibly a beard. The French inscription in the Codex translates: “Marine monster killed by the French on the Richelieu River in New France.”

Despite French attempts to eradicate this creature, rumours abound that the mysterious river creatures still swim in the waters surrounding the island of Tiohtià:ke / Montreal to this very day.

The St. Lawrence River Valley, which the Mohawks call Kaniatarowanenneh, or the “big waterway,” has a rich history of Indigenous use and occupation dating back over 9,000 years. Today’s river valley was submerged under a large inland sea until around 10,000 years ago when glacial melting caused the waters to drain into the Atlantic Ocean. Today, many scientists call this former body of water the “Champlain Sea”.

As the waters drained, the resulting area was seen as ideal for habitation and transportation. Kaniatarowanenneh was a large river system with many tributaries, islands and archipelagos. The soils were fertile and it wasn’t long before the ancestors of today’s Mohawk and Haudenosaunee First Nations began establishing trap lines, villages, trade routes, farming lands and the great city of Hotsirà:ken on today’s Tiohtià:ke / Montreal Island.

According to Mohawk Oral History expert Dr. Michael Doxtater: “Hotsirà:ken is an ancient ancestral place, an Indigenous place. It was a Mohawk village of around 5,000 people on the island.”

“The island was what I would call a metropolitan trade centre. The Algonquin people would come down the Ottawa River, [people] would come down from the Innu territories up the St. Lawrence and then there would be the various Iroquois linguistic groups that would converge and that was a major, major trade centre.”

With Hotsirà:ken being surrounded by water and trading via canoes on the rivers, it is perhaps not surprising that Mohawk legends and stories often feature water.

Indeed, the Mohawk Creation Story involves the formation of lands on the back of a giant turtle in endless waters. When Atsi’tsaká:ion, or Sky Woman, falls through a hole in the sky world of Karonhiá:ke, she creates lands on the back of the turtle with the help of various animals and creatures.

Today, the land of North America is often referred to as Turtle Island.

Concerning the river creatures, they were described by First Nations such as the Mohawks and the Omahas (on the Missouri River) as a group of monster serpents who were extremely territorial and attacked anything that ventured close to their aquatic domain.

Many people lived in such fear of these creatures and even the mightiest warriors would avoid traveling the river alone. The creatures were known to attack without provocation and would challenge all those who dared to enter their territory in a canoe.

These river monsters were known as Wakandagi.

According to the legend:

“These aquatic beasts were said to be extremely long, serpent-like in body shape, and were covered in scales. They possessed an extremely thick tail, had four deer legs complete with hooves, a face that appeared to be the mix between a deer and a snake, and large antlers upon their heads. Even though the beasts had legs, they remained within the water at all times and chose to live exclusively within the caves along the river.”

“Despite being extremely territorial, aggressive, and occupying almost every mile of the river, the Wakandagi were rarely seen. One was only able to view them during hours where the river and its outlets were covered in fog or mist. But just because the fog and mist would eventually fade as the day went on didn’t mean that the Wakandagi would go dormant.

These river monsters would continue to flip every canoe that they encountered on their waters and would attempt to drown and consume every occupant within it. All while remaining completely unseen.”

The storyteller concludes:

“It was widely believed that even though the creatures hated all that ventured into their waters, they hated those that ventured in alone the most. The Wakandagi were said to challenge these lone warriors by throwing spheres of water at them rather than flat out drowning them.”

“If a warrior spotted at water sphere flying towards them and it were to land inside their canoe, they were supposed to pick it up and throw it back at the beast. If they failed to do so – or did so too late – the sphere would explode and kill the warrior, ultimately flinging their body into the water to be consumed by the monster below. If the warrior was able to throw the sphere back at the creature in time, it would end up exploding and wounding the Wakandagi and thus proving the warrior was worthy enough to cross the river safely and without further incidents from other creatures.”

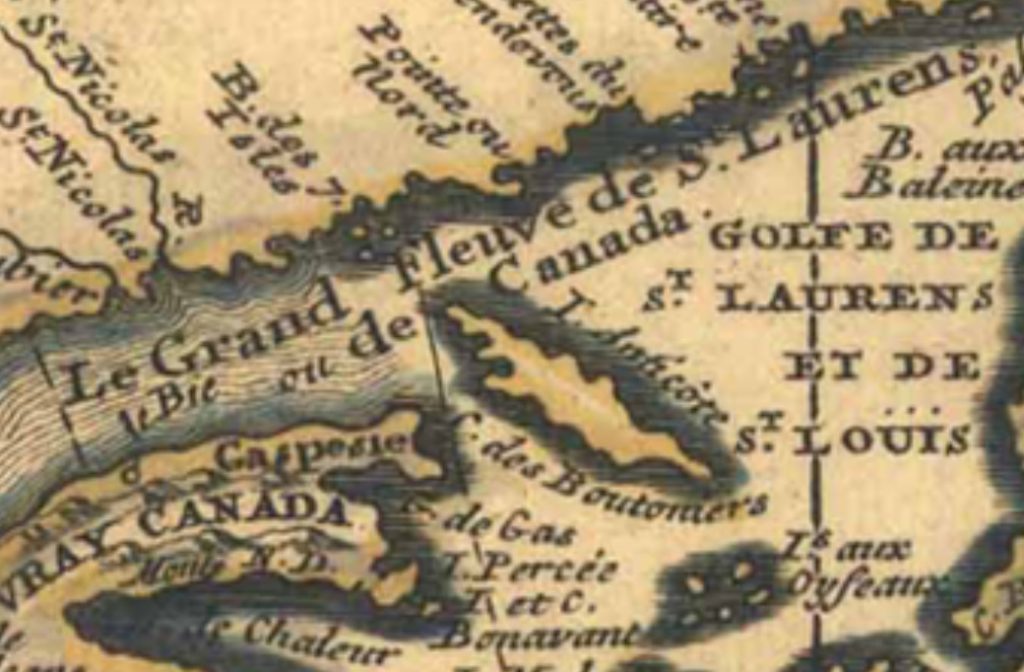

When French explorer Jacques Cartier arrived in the river estuary of Kaniatarowanenneh on August 10th, 1535, he re-named it the “Gulf of Saint Lawrence” in honour of the Saint’s Feast Day.

When the French began to colonize the shores of Kaniatarowanenneh in the early 1600s, the name “Fleuve Saint-Laurent” (St. Lawrence River) came into colonial usage.

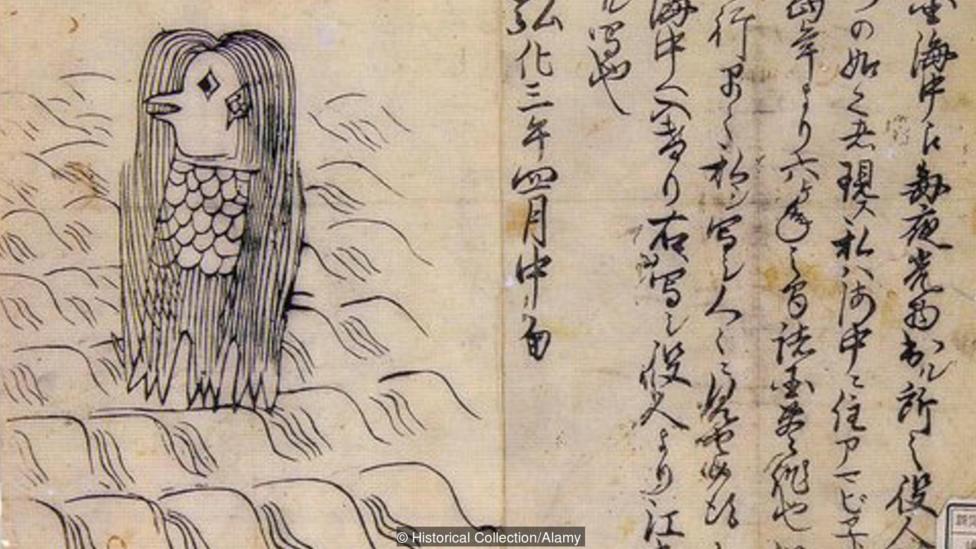

Jesuit missionary Louis Nicolas journeyed throughout the territory from 1664 to 1674 and created an album of drawings entitled Codex Canadensis. The drawings were meant to illustrate a manuscript by Nicolas entitled Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales, but it was never published as the missionary had hoped.

A strange creature combining a fish tale with a human torso appears on Page 59 of the Codex shows.

The face is rather feminine with long hair, but under the chin are appendages, which are perhaps fins or a beard. The torso and arms are scaly, the “hands” appear as smaller fishtails. The torso is separated from the large fishtail by a broad band or ridge. Nicolas’ French inscription translates as: “Marine monster killed by the French on the Richelieu River in New France.”

The Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales does not supply further information about this river creature.

When exactly the monster was slain is unknown, and what exactly it was remains a mystery. It is possible that Nicolas worked from an oral description, since there is no indication that he was present during the slaughter of the monster.

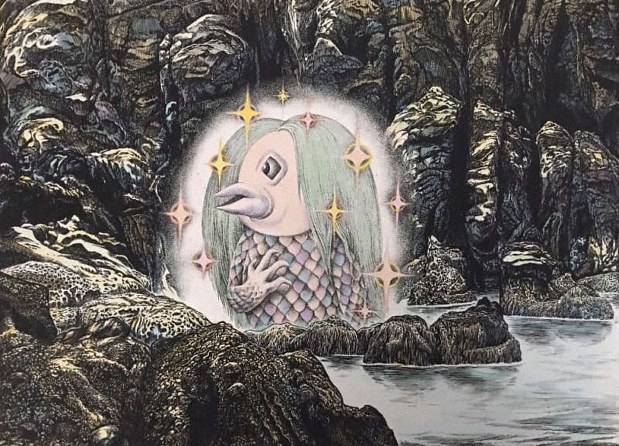

It is noteworthy that mysterious aquatic creatures appear in folklore throughout the world. In one recent case in Japan, an old legend resurfaced involving a mermaid of some sort known as Amabie. First documented in 1846, Amabie is an auspicious yokai, or class of supernatural spirits within Japanese folklore that can bring predict the future and offer protection.

According to the BBC:

“As the story goes, a government official was investigating a mysterious green light in the water in the former Higo province (present-day Kumamoto prefecture). When he arrived at the spot of the light, a glowing-green creature with fishy scales, long hair, three fin-like legs and a beak emerged from the sea.”

“Amabie introduced itself to the man and predicted two things: a rich harvest would bless Japan for the next six years, and a pandemic would ravage the country. However, the mysterious merperson instructed that in order to stave off the disease, people should draw an image of it and share it with as many people as possible.”

With the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the story of the sea creature Amabie has resurfaced and many people are drawing her and broadcasting the images in hopes of protecting themselves from the dreaded coronavirus.

Closer to the island of Tiohtià:ke / Montreal, legendary marine creatures still capture imaginations as well. Because the rivers, lakes and watersheds are often inter-connected, there is a wide range of marine environments for mysterious creatures to live and roam.

One such example is Champie, a mysterious creature that is said to inhabit today’s Lake Champlain to the south.

Over the years, there have been over 300 reported sightings of the lake monster, including one by French cartographer Samuel de Champlain, the founder of Québec and the lake’s namesake. Champlain is alleged to have documented a “20-foot serpent thick as a barrel, and a head like a horse.”

More recently, modern theories related to Montreal’s River Monsters have emerged. According to scientists, it is possible that errant Greenland sharks sometimes swim up the river, possibly as far as Montreal and beyond. While normally the river waters are teeming with bass, muskies, trout, salmon, pike, walleye, perch, carp, sturgeon, channel catfish, perch, sunfish and rock bass, sometimes larger creatures swim upstream, such as rogue sharks and whales.

Discovery Canada presented St. Lawrence: In Search of Canada’s Rogue Shark to examine the theory, explaining that although unlikely due to the fresh water, it is entirely possible that these large marine creatures can endure long inland voyages.

Lending credence to this theory was an errant beluga whale who visited Montreal’s old harbour in the autumn of 2012.

Belugas, like Greenland sharks, normally live in the saltwater around Tadoussac, about 500 kilometers upstream, and well-beyond into the depths of the Atlantic Ocean.

Lastly, there was a sighting several years ago by a surfer enjoying the freestanding waves behind Habitat 67. She had been out on the waters for a few hours in late May, 2014, when she spotted something strange that appeared to be swimming upstream through the rapids.

She described it as “looking like a cross between a big snake and a fish with fins”, adding “ it was something dark and slimy, about as long as a bus but not nearly as thick, slithering its way through the rocks and waves in the Lachine Rapids. Never seen anything like that before, even in the ocean.”

In conclusion, from the ancient times when the lands were covered in a giant sea to the present day’s rivers, lakes and archipelagos, all sorts of marine creatures have been plying the waters in the area where the island of Tiohtià:ke / Montreal exists today and far beyond.

That fact some of these creatures are legendary marine monsters, with stories dating back thousands of years, gives pause as to the potential dangers lurking in the river just off the island’s shoreline.

Enter the waters at your own risk!

Company News

Haunted Montreal takes the health and safety of our staff and clientele very seriously and health experts have issued directives for COVID-19. Because social distancing policies are in effect and “non-essential” gatherings are forbidden, all tours are currently suspended.

Despite the suspension of all current tours due to COVID-19, our full 2020 season of public tours is now online and tickets are still on sale. Please note that in the event the tour is suspended due to COVID-19, clients will receive a full refund or, if preferred, a rain check.

We hope conditions will improve soon so we can begin offering our tours and experiences again.

Haunted Montreal would like to thank all of our clients who attended a ghost walk, haunted pub crawl or paranormal investigation during the 2019 – 2020 season!

If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page, something that helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours.

Lastly, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list.

Coming up on June 13: Ruins of Saint Ann’s Church

Nestled in booming Griffintown is a beautiful park that doubles as an old reminder when the condo-choked neighborhood was once Canada’s most infamous Irish shantytown. St. Ann’s Park contains the ruins of a church that bore the same name. Once the bustling hub of the Griffintown community, the beloved church was unceremoniously demolished in 1970 as part of an “urban renewal” project. Since then, the grounds have witnessed numerous paranormal activities and many new condo-owners are convinced the park is haunted.

Donovan King is a postcolonial historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbott College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec). He is also a certified Montreal Destination Specialist.

Love your blog. Actually re-read them throughout the month. Full of info that is just too much for one sitting! ????