Nestled among the new condo towers in western Griffintown, the Montreal Art Center and Museum stands out like a rare gem. It occupies the former 1879 Caledonian Iron Works factory, a Victorian-era company that produced engine parts for ships and trains, turbines and other complex metalworks. Today, the Montreal Art Center and Museum is considered as one of the most historical - and haunted - buildings in Griffintown.

Welcome to the fifty-first installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog!

With over 300 documented ghost stories, Montreal is easily the most haunted city in Canada, if not all of North America. Haunted Montreal is dedicated to researching these paranormal tales, and the Haunted Montreal Blog unveils a newly-researched Montreal ghost story on the 13th of every month! This service is free and you can sign up to our mailing list (top, right-hand corner for desktops and at the bottom for mobile devices) if you wish to receive it every month on the 13th!

With the Hallowe’en season behind us, Haunted Montreal is moving into winter mode. We are pleased to announce that the Haunted Montreal Pub Crawl runs year round on Sunday afternoons. We are also looking for an indoor haunted location for our new Paranormal Investigation.

Lastly, our ghost walks can still be booked for private groups, including Haunted Mountain, Haunted Griffintown and Haunted Downtown, weather conditions permitting.

Our November blog examines the Lachine Canal, one of Canada’s most haunted waterways. Today the site of a linear greenspace run by Parks Canada, the canal has witnessed hundreds of drownings, especially during the era of Industrialization. It is also littered with many old factories and silos, some repurposed into condominiums, several of which are reputed to be haunted. Ghostly ships are known to ply the canal and various spirits are known to wander the banks.

Haunted Research

The Lachine Canal is widely considered to be one of Montreal’s most haunted places. During the day, its banks are bustling with cyclists, dog-walkers, people having picnics and sunbathers, but at night it is a different story. The polluted waterway is a dark, eerie and desolate place reeking of the paranormal.

Since the canal officially opened in 1825, hundreds of people have drowned in its dark waters. These included suicides, murder victims, people who drowned while swimming and those who died during industrial accidents. The polluted banks are also peppered with old buildings, many being repurposed into condominiums, that are reputed to be haunted. Last but not least, not only are ghost ships known to ply the canal’s waters, but there are also an unknown number of bodies buried along its length. Mostly victims of the Irish Famine of 1847, these forgotten corpses of desperate refugees result in all sorts of ghosts and paranormal activity along the canal.

Historically, a portage trail existed along roughly the same trajectory of today’s canal.

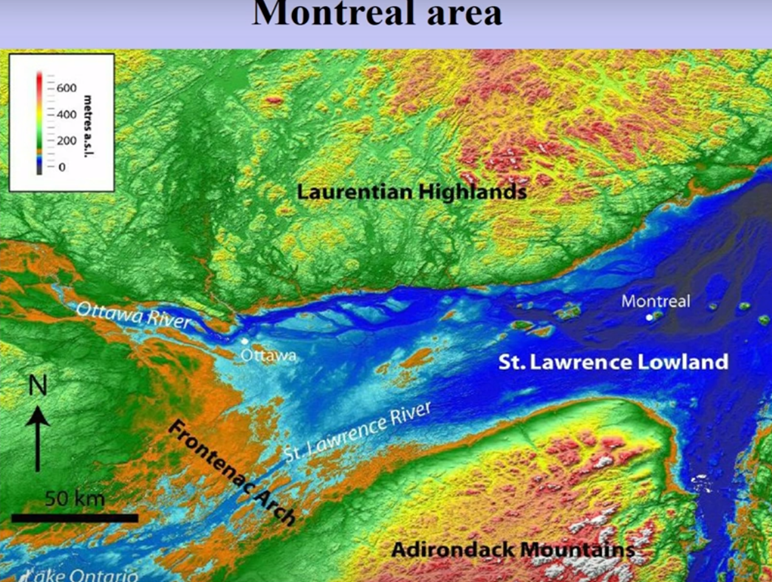

Today’s Island of Montreal / Tiohtià:ke was formed approximately 10,000 years ago when an ancient sea drained away with the melting of glaciers. Geographically, the archipelago is an ideal location for trade, with 12 rivers pouring into the area. Furthermore, anyone coming into the area was forced to stop and portage canoes, given that the islands are surrounded by dangerous rapids.

As such, the ancestors of today’s Kanienʼkehá꞉ka or Mohawk First Nation established Hotsirà:ken, a city of around 5,000 people, which thrived on the island.

According to Dr. Michael Doxtater, a Mohawk Elder and specialist in Indigenous oral knowledge:

“Hotsirà:ken is an ancient ancestral place, an Indigenous place. The island was what I would call a metropolitan trade centre. The Algonquin people would come down the Ottawa River, [people] would come down from the Innu territories up the St. Lawrence and then there would be the various Iroquois linguistic groups that would converge and that was a major, major trade centre.”

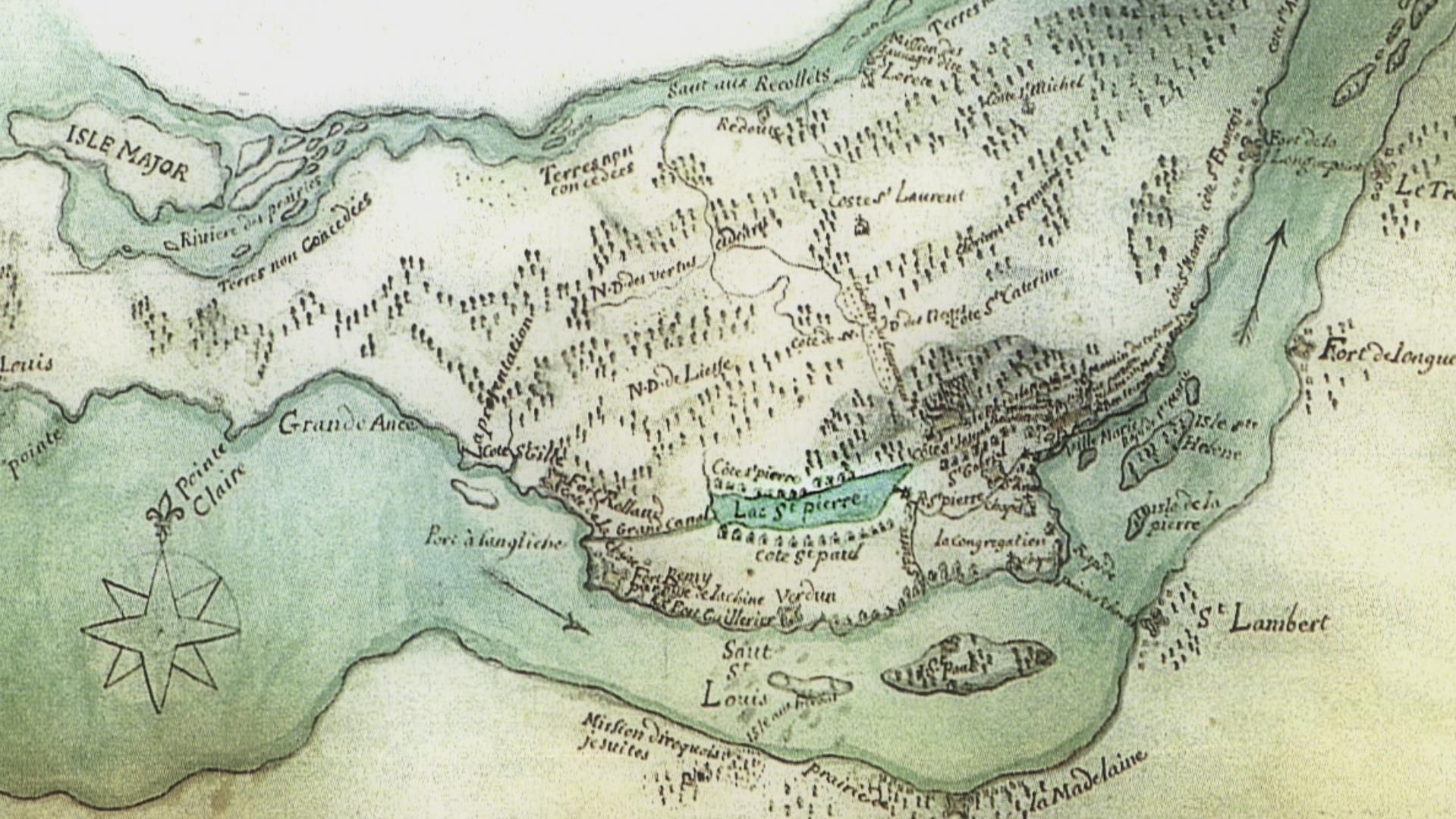

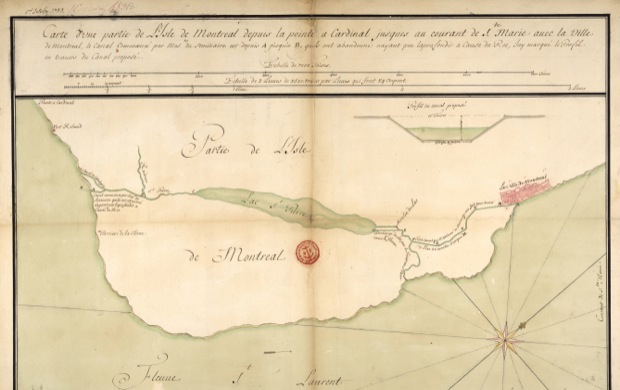

The portage trail where the Lachine Canal is located today followed a small river that led to a shallow lake. Before the arrival of the French colonists, the banks of the lake were cultivated by the ancestors of today’s Kanienʼkehá꞉ka or Mohawk First Nation.

The French would later name the small river “St. Pierre” and the shallow lake “Lac aux Loutres” or “Lac à la Loutre”, which means “Otter Lake” in English.

There are several theories about the origin of the name of the lake. The otter can be likened to the beaver in French. Some say the name comes from the fact that the lake was home to a large beaver population in the 16th century. According to another story, the indigenous people who cultivated the surrounding lands gave the lake this name because of its shape. It was also said that Otter Lake symbolized the baby beaver that slept in the womb of the beaver mother, namely Tiohtià:ke or today’s Montreal island.

Starting in 1534, colonization problems began to occur on Tiohtià:ke. French explorer Jacques Cartier, on a voyage of exploration, attempted to claim the entire Indigenous territory of Turtle Island (today’s North America) for the French King, Francois I.

On July 24, 1534, Jacques Cartier planted a cross in today’s Gaspé region, a Catholic symbol that the King of France was trying to claim the territory as his own through a now-discredited Catholic doctrine called Terra Nullius.

The following year, Jacques Cartier arrived in Tiohtià:ke on October 2. He could not pass the islands due to the dangerous rapids that surrounded them. He was welcomed with great hospitality by the Mohawk villagers and leader of Hotsirà:ken. The Kanienʼkehá꞉ka hosts offered a feast of food and even provided Indigenous tour guides to Jacques Cartier so he could scale the great mountain Otsirà:ke to survey the western area beyond the rapids. It is noteworthy that Cartier promptly tried to rename Otsirà:ke as “Mount Royal” in honor of his patron.

He also mis-spelled Hotsirà:ken as “Hochelaga” in his journals.

The following day, Jacques Cartier turned his ships around and sailed back eastward up the river. Cartier’s visit would foreshadow the horrors that were about to be brought on by French colonization.

When the French began to colonize, they started in the east with settlements including Tadoussac (1599), Port Royale (1605), Quebec City (1608) and Trois-Rivières (1634).

Tiohtià:ke was seen as off-limits because it was a well-known part of the Mohawk territory and the Mohawk warriors were seen as among the fiercest in the land.

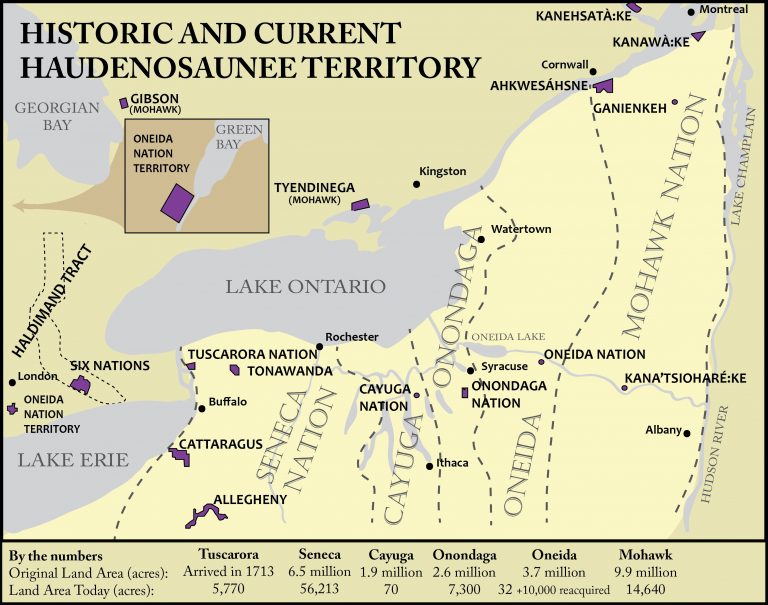

They were also part of a Confederacy of five nations known as the Haudenosaunee, which consisted of the Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga and Mohawk First Nations.

With French colonization came deadly epidemics such as smallpox that had never been encountered before by Indigenous people. The French also began forming military alliances with other First Nations who were not on friendly terms with the Haudenosaunee. With intermittent warfare and wave after wave of smallpox, the residents of Hotsirà:ken moved further south into Mohawk territory to try and avoid the diseases and warfare and to strategize.

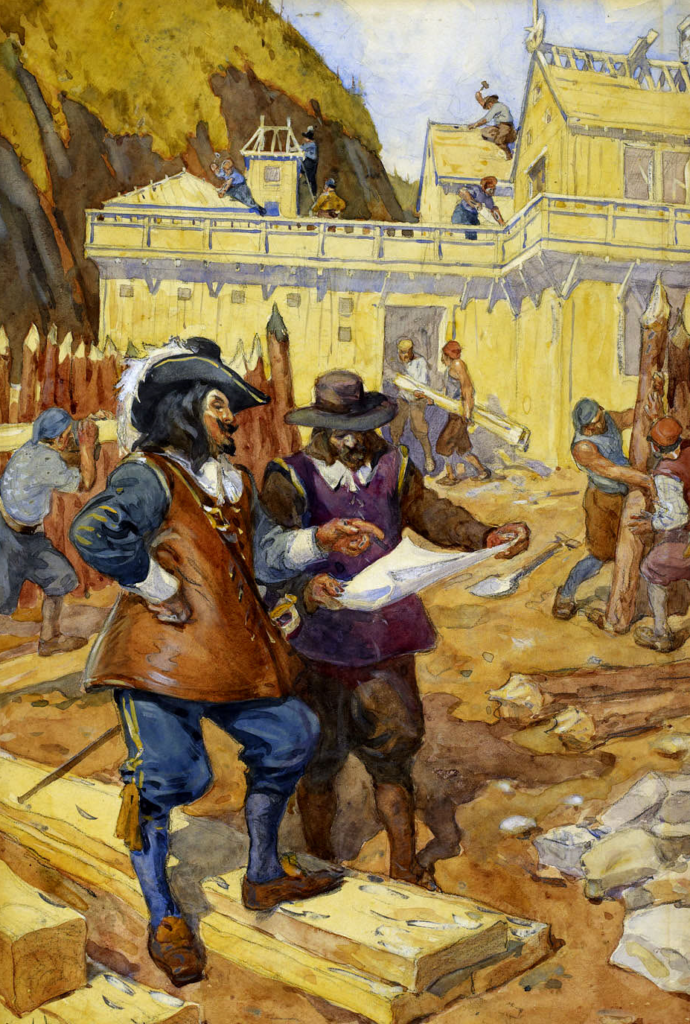

Meanwhile, in Paris in 1639, Catholic zealots Jérôme le Royer de la Dauversière, Jean-Jacques Olier and Pierre Chevrier founded the Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal pour la conversion des Sauvages de la Nouvelle-France (The Society of Notre-Dame de Montréal for the Conversion of the Savages of New France). Le Royer claimed that God had visited him during a dream and instructed him to do so.

The religious organization founded the colony of Ville-Marie on Tiohtià:ke in1642, sparking an all-out and brutal war between the French and their allies and the Haudenosaunee, which lasted until 1701.

Today’s canal is situated on land originally “granted” by the King of France to the Sulpician Order. Beginning in 1689, attempts were made by the French Colonial government and several other groups to build a canal that would allow ships to bypass the treacherous rapids. Sulpicians François de Salignac Fénelon and Dollier de Casson spearheaded the first plans to dig the canal.

The need for of a canal to bypass the rapids was a major concern since the beginning of European colonization. In 1680, the Sulpicians had planned to build a canal between Ville-Marie and the village of Lachine to connect the various watercourses in the region.

The word “Lachine” derives from French “la Chine” (China), and was named in 1667, apparently in mockery of its then owner Robert Cavelier de La Salle. He was known to explore the interior of the continent in an effort to find a passage to Asia. When he returned without success, he and his men were derisively named “les Chinois” (the Chinese). The name was adopted when the parish of Saints-Anges-de-la-Chine was created in 1678, with the name Lachine appearing on subsequent maps for both the rapids and the village.

The canal, which would have been the first in North America, was never completed due to a lack of funding, although several large sections were dug starting in 1689.

Following the British Conquest of 1760, there was a renewed interest in digging the canal. In 1821, a budget was prepared and 200 Irish navies from Griffintown were hired to dig the project.

After four years later of back-breaking labour, the canal was completed and opened to shipping traffic.

It wasn’t long before the canal needed to be deepened to allow heavier ships to pass through and to harness hydraulic power for the industries located on its banks. Work began in 1843, but trouble started immediately when construction work was privatized and worker’s received a wage cut of a shilling a day, almost 30% of their salary! This sparked the first strike in Canadian history, as workers stopped digging and demanded a wage increase, at both the Lachine and Beauhornois canals.

At Beauhornois, authorities were alarmed and 50 soldiers from the 74th Regiment, under Major Campbell, were brought in. Magistrate Laviolette read the Riot Act, and when the workers refused to disperse, he yelled out: “Major Campbell, fire!” The soldiers raised their muskets and fired into the crowd of navies, causing a scene of panic. At least 6 workers were killed by bullets, 4 of them shot in the back as they fled.

A priest on the scene named Father Falvey cursed the magistrate, calling him a coward and murderer. However, an inquiry later cleared the government, declaring it to be a case of “justifiable homicide”. It was a dark moment in the canal system’s history.

By 1850, factories were springing along the canal’s banks. With the enlargement of the Lachine Canal and its plentiful hydraulic power, huge foundries, factories, and metal works were built, their smokestacks spewing out noxious, black clouds. Giant ships would frequently dock to load and unload cargo and the area was soon known as the Canada’s cradle of industrialization.

Residents of working-class neighborhoods like Griffintown were put to work in the factories, often for 14 hours per day, 6 days a week, in grueling conditions. Women and children, some as young as 6 years old, earned a lot less than a man for the exact same job.

With no environmental standards in place, the Lachine Canal and its banks were soon heavily polluted with dangerous chemicals and metals such as chromium, lead, zinc, copper and mercury.

This continued until around the 1950s, when the expansion of the port and opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959, on the other side of the river, made the Lachine Canal obsolete.

The factories began closing up shop and over 20,000 people were put out of work. The neighborhood began dying as people moved away in search of better prospects.

The canal was neglected, and at one point, the entrance was used as a dump for debris from the Expo 67′ Metro construction, closing it to shipping. Eventually it was re-excavated and Parks Canada took over in 2002, transforming the canal into a linear park with a bike path.

As for the pollution, they decided to simply not disturb the contaminated sediments at the bottom of the canal. The pollution is still down there, a twisted reminder of the canal’s deranged history.

Today, the canal has ghosts and hauntings all along its 14.5 km trajectory, both in the dark waters and along the shoreline, including in many of the old buildings.

Starting in the water itself, there are reports of ghost ships plying the waterway and the spirits of the dozens of people who drowned in the canal. Coolopolis author Kristian Gravenor researched some of these drownings in his blog:

“The waters have not spared children or elderly women, as people of all types breathed their last breaths before their bodies were fished out in macabre scenes all too familiar to city-dwellers. Many were suicides, others murder victims and many others were people who just drowned after swimming or slipping in fully-clothed.”

Former Griffintown resident Denis Delaney described children swimming in the canal and drowning when boats suddenly shifted against the banks, forcing the doomed kids under the water.

Gravenor describes the Lachine Canal as a “watery graveyard” and “Montreal’s spookiest place.” The spirits of the drowned can sometimes be heard in the waters and manifest themselves as unusual splashes, waters thrashing about for no reason and gurgling noises emanating from the depths of the canal.

There were also countless industrial accidents along the Lachine Canal, which resulted in hauntings.

For example, the spirit of a nervous young boy wearing a black suit has been spotted on several occasions on the Swing Bridge. He appears to be running across the length of the bridge before leaping and disappearing into thin air.

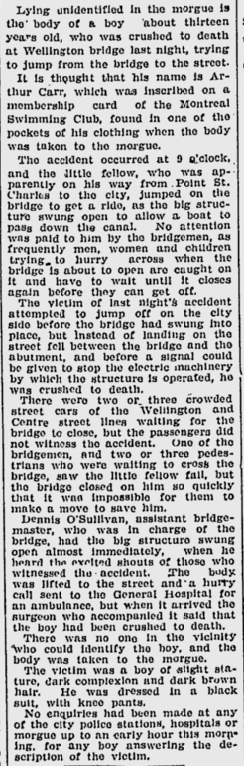

There is a theory as to who this ghost might be. At around 9 pm on the evening of Tuesday, September 17, 1908, a little boy was attempting to cross the Lachine Canal from the south side by using the Swing Bridge. He was wearing a black suit with knee-high pants. The bridge was designed to swing 90 degrees to allow canal boats through, meaning cars and pedestrians had to wait for a ship to pass before the bridge swung back into place.

When the boy arrived on the south side, the bridge began to swing to allow a boat to pass. He jumped on the bridge to catch a ride across the canal. The bridge-keeper didn’t notice, as many pedestrians in a hurry would jump on the bridge as it swung. They had to wait in the middle as a ship passed. Once the ship was through, the bridge began swinging back into its regular position, connecting both sides of Wellington Street.

Unfortunately, the boy attempted to jump off on the Griffintown side before the bridge had swung fully into place and instead of landing on the street, he fell between the abutment and the bridge. He was crushed before the bridge-keeper could cut the electricity to the structure.

When the bridge-keeper realized what had happened, he swung the bridge back out again and people pulled up the mangled body of a teenage boy with brown hair of about 13 years old. In his suit pocket was a Montreal Swimming Club Card bearing the named Arthur Carr. An ambulance brought him to the General Hospital but the surgeon on duty noted that the boy was killed instantly when crushed by the Wellington Swing Bridge. The boy was placed in the morgue, but nobody claimed his body. Instead, it was sent to Anatomy.

The most prominent theory about the haunting is that young Arthur Carr’s ghost remained after the tragic accident that killed him. He was probably in a hurry to get home to the Griff after attending some sort of church function on the other side in Point Saint Charles, which may be why he was so well-dressed. Sometimes when a person is killed suddenly, their ghost returns but is not aware that they are actually dead. There is speculation that the ghost of the boy appears because he is still trying to return to his family home in the Griff after all these years.

Running below the rusting Swing Bridge is the decrepit and abandoned Wellington Tunnel, another haunted site. Desolate and foreboding, crumbling and graffiti-scrawled, the tunnel is strewn with garbage and its hidden entrance is sealed off with concrete blocks and prison-like iron bars. The place feels extremely creepy and dangerous and is known to house several ghosts, including one of a man carrying a bucket of blood. It was covered in the #7 Haunted Montreal Blog.

As for the buildings, one of the most famous hauntings occurred in the Redpath Sugar Refinery when it was abandoned and used as shelter by homeless people. According to the Narcity Blog:

“The bike path that runs along it passes several haunted buildings, like the former Redpath factory, for example. A spirit would wander with the mission of dislodging the homeless people squatting the place by chilling the air and releasing an abominable stench.”

Today, the Redpath is the site of luxury condominiums and it is unknown if these paranormal activities continue for the more affluent residents who live there now.

Other buildings that are reputed to be haunted include Silo #5, the Belding Paul & Co. Limited Buildings, the Old Malt Factory and the Fur Trade Museum in Lachine.

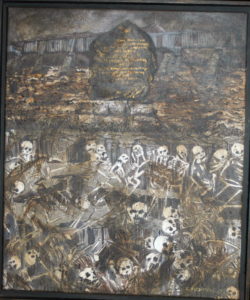

Going further back in time, the Lachine Canal was also hard hit by the Irish Famine of 1847, resulting in many more ghosts and paranormal activities. One of these includes a regiment of ghostly British Redcoats, who have been spotted marching along the banks in military unison with bayonets in the air.

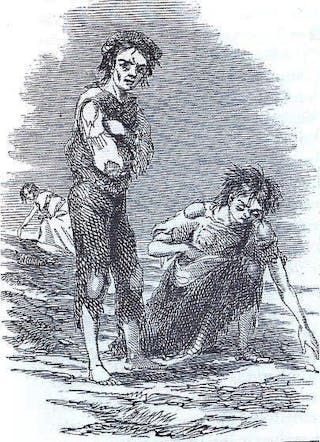

In the summer of 1847, Montreal was a city of 50,000 people. Due to the famine exacerbated by British colonial inaction, Montreal was completely overwhelmed by 75,000 Irish refugees, most of whom made the crossing on “coffin ships”. Many were suffering from starvation and typhus, a highly contagious disease.

Due to a shortage of canal boats, many of the refugees chose to walk the canal path to Lachine. According to reports, many of them died on the banks of the canal and were buried on the spot in unmarked graves.

Despite aid from various religious institutions and Mayor John Easton Mills himself, the death toll that year was staggering: in addition to the 6,000 Irish victims, almost 1000 Montreal residents, at least 8 Catholic priests, thirteen nuns, and seven Anglican clergymen also perished from typhus.

In early November, the Mayor dropped out of sight and citizens began to wonder what had happened to him. It turns out that Mayor Mills contracted typhus himself during his duties. According to his doctor, he never issued a word of complaint about the pain or his misfortune. He died on November 12, at the young age of 54. An elaborate funeral was held and he was declared “Montreal’s Martyr Mayor” for his heroic efforts.

His ghost is known to wander the site of Montreal’s first fever sheds, at the Wellington Basin on the south side of the canal, late at night. It is as though he is still caring for his charges in a paranormal afterlife.

Thousands of orbs have also been photographed at this site, sometimes floating about in the air. One local resident went into a trance and the orbs appeared to him.

He felt as though the dead were wailing, perhaps a likely paranormal occurrence given that the site also contains the first Irish Famine cemetery, which is presently not marked in any way.

The full horrors of the impact of the Irish Famine are covered in the #35 Haunted Montreal Blog.

In conclusion, the Lachine Canal is indeed a very haunted waterway. Wandering its eerie banks at night is a spooky experience, one not recommended for the faint of heart. It’s advisable to go in pairs or a group, because you never know what might be luring in the dark waters, the old factories or the haunted shoreline of the Lachine Canal!

Company News

Haunted Montreal is has concluded the Hallowe’en Season and is moving into winter mode! For this first time ever, we will be operating year-round with our award-winning Haunted Pub Crawl, every Sunday at 3 pm in English and 4 pm in French.

Private tours are also available, weather permitting, for Haunted Mountain, Haunted Griffintown, Haunted Downtown, the Haunted Pub Crawl and our new Paranormal Investigation into the old Saint-Antoine Cemetery.

Haunted Montreal has also launched our first promotional video ever! Please share it if you like it!

We are also proud to announce that I, Donovan King, have been accredited as a “Montreal Destination Specialist” by Tourisme Montréal. I will use these skills to improve our tours and to continue to develop new experiences as we put Montreal on the map as Canada’s most haunted destination.

Haunted Montreal would like to thank all of our clients who attended a ghost walk, haunted pub crawl or paranormal investigation during the 2019 season! If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page, something that helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours. Lastly, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list.

Coming up on December 13: Hôpital de la Miséricorde

The former Hôpital de la Miséricorde is just one of many now-vacant hospital complexes in Montreal, in the wake of decisions to centralize hospital services. During its sordid past, thousands of orphans were falsely diagnosed with mental illnesses and single mothers were housed in hostile conditions within the walls of the former “Hospital of Mercy”. Today, the building is abandoned by the living – but certainly not by the dead! Considered a paranormal hotspot by experts, there are many stories of disembodied children’s voices crying, sounds of clanging, strapping and other abuse, not to mention the appartitions of angry nuns and a fearful young mother.

Donovan King is a postcolonial historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbott College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec). He is also a certified Montreal Destination Specialist.

Thank you very much for your excellent historic summaries !

They are all great, but the Lachine Canal was a “knockout”.

I have been preparing a summary of industry along the canal to indicate the flourishing manufacturing which took place, especially between the mid 19th Century through WW II. However, as you point out so well, it took place at an enormous human and environmental coast. This also applies to the imposed catastrophes of the destruction of the boreal forests and the rich eco-systems which once existed there, despite the harsh climate. As an example, in one particular year, 10 million pelts were exported from Quebec – an unimaginable holocaust for nature and the indigenous peoples.

With best wishes,

Jim