Nestled among the new condo towers in western Griffintown, the Montreal Art Center and Museum stands out like a rare gem. It occupies the former 1879 Caledonian Iron Works factory, a Victorian-era company that produced engine parts for ships and trains, turbines and other complex metalworks. Today, the Montreal Art Center and Museum is considered as one of the most historical - and haunted - buildings in Griffintown.

Welcome to the thirty-fifth installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog! Released on the 13th of every month, the March 2018 edition focuses on research we are carrying out into the Black Rock, a granite boulder memorial that marks Montreal’s Irish Famine cemetery. Much of the city’s Irish community is still haunted by memories of the terrible episode in 1847, when 75,000 Irish refugees disembarked after crossing the Atlantic Ocean on coffin ships. Haunted Montreal is currently in winter mode and is not offering any more public ghost tours until May, 2018.

HAUNTED RESEARCH

The Black Rock, or Irish Stone, holds an important place in the heart of Montreal’s Irish community. Sometimes a city can be haunted by an event so tragic that it leaves dark, indelible traces in the public imaginary. This feeling of being haunted by a terrible past can be exacerbated when the commemorative site to mark the tragedy is compromised. Such is the case with Montreal’s Black Rock, the first monument in the world dedicated to Black ’47, the year tens of thousands of Irish refugees crossed the Atlantic Ocean aboard “coffin ships” in search of a better life.

Unlike a typical ghost story that focusses on apparitions and the paranormal, this story is about how citizens are haunted by a dark, ingrained memory.

The Black Rock is the guardian of Montreal’s Irish Famine Cemetery. The graveyard is presently criss-crossed by an urban blight of highways, railway tracks, parking lots, electricity pylons and industrial billboards. The commemorative site is largely inaccessible and consists of the Irish Stone, a massive black boulder, squeezed onto a tiny traffic island straddled between two busy highways on Bridge Street. In an unsightly industrial zone, gaudy advertisements on giant billboards glare down on the Black Rock, which is encircled by a wrought iron fence peppered with rusting metal shamrocks.

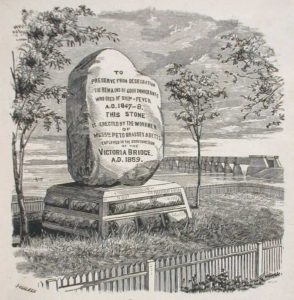

Installed in 1859, after workers discovered human remains while building the Victoria Bridge, the Black Rock was dredged up from the river and placed atop the graveyard to mark the Famine cemetery. The monument’s purpose is engraved in the stone: “To Preserve from Desecration the Remains of 6000 Immigrants Who died of Ship Fever A.D. 1847- 48.” Today, its purpose is largely forgotten by the thousands of commuters speeding past every day. From a commemoration point of view, Montreal’s Irish Famine Cemetery can perhaps best be described as “disgraceful”.

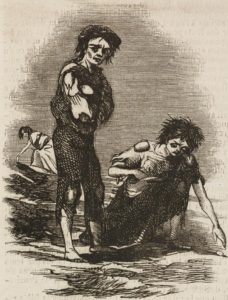

In the summer of 1847, Montreal was inundated with thousands of desperate Irish Famine refugees and was totally unprepared to deal with the influx. Known in the history books as Black ’47, it is the year more than 75,000 Irish Famine refugees landed on Montreal’s wharves. At the time, Montreal’s population was only 50,000 people, so the city was completely overwhelmed. Many of the refugees were hungry, emaciated and diseased.

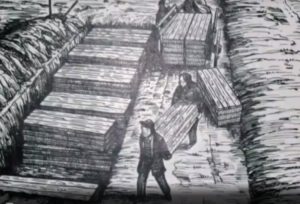

Fleeing brutal political oppression and a potato famine in Ireland, these emigrants suffered dangerous crossings over the Atlantic Ocean on what were described as “coffin ships”. Never designed to transport human beings, these were rickety ships that transported Canadian lumber and other products to Europe and took on human cargoes of desperate refugees, on the return crossing, to supplement profits. Hundreds of often-starving families were crammed below-deck and forced to live in overcrowded and filthy conditions. The food wasn’t nutritious and there wasn’t even enough water for washing during the 3 month crossing, only for drinking. With only buckets being used for toilets, the holds of the ships soon became contaminated with human waste.

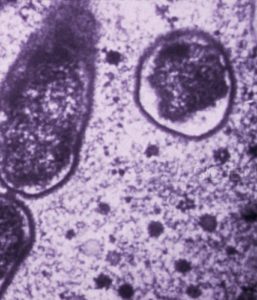

This proved to be the perfect breeding ground for a deadly epidemic disease known as typhus. Also called Ship’s Fever, it is transmitted by fleas and lice infected with the rickettsiae bacteria, which breed in filthy conditions and feed on humans. Scratching the bite would allow the bacteria to enter the bloodstream and replicate.

The incubation period was 1 – 2 weeks. Those infected could expect a high fever, headache, dull pains and loss of appetite. On the 5th day, a rash would appear on the abdomen and the face would become bloated and congested. Many victims would develop complications, including a clouded mental state, followed by muscular twitchings, then delirium. The final stage was a deep stupor before the skin took on a dusky hue and turned black before the victim died. The mortality rate was estimated at about 30% – 50%.

From the coffin ships, diseased corpses were thrown overboard during the crossing.

Schools of sharks were often spotted trailing the vessels. As they entered the Saint Lawrence River, they approached a quarantine station that had been set up at Grosse Ile, near Quebec City. The station witnessed thousands of deaths but could not contain the epidemic.

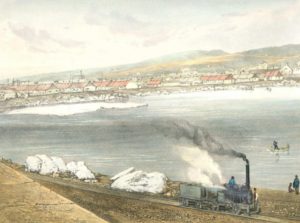

It moved upriver towards Montreal after passengers transferred onto steamships at Quebec City. Montreal was at the end of the long sea journey because the Lachine Rapids prevented ships from continuing westward. To do so, passengers had to transfer onto smaller boats to traverse the Lachine Canal.

Montreal’s Famine challenges began on June 7, 1847, when 2,304 typhus-stricken Irish migrants disembarked on the city’s wharves. It was just the beginning of a long and difficult summer as Montreal was inundated with thousands of the most debilitated and wretched beings ever thrown upon its shores. Many of the sickly refugees collapsed on Montreal’s wharves in the Calcutta-like heat that was baking the city that summer.

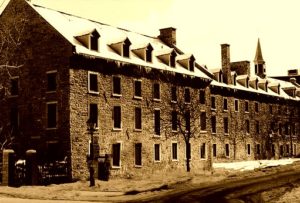

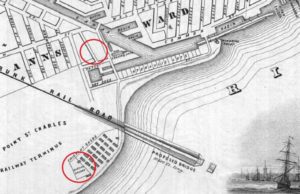

There were only two fever sheds, to the south of Wellington Bridge, that were left over from a cholera epidemic in 1832. Those sick with typhus were directed there from the docks of Montreal.

Before long, these sheds were overcrowded centers of filth and misery, with stinking corpses littering the nearby fields. Many of the bodies were buried randomly on the banks of the canal until a plan was later hatched to dig burial trenches near the site.

The Grey Nuns, who were located nearby in their Motherhouse, sprang into action to care for the sick and dying emigrants.

Their first-person account can be found online at the digital archives at the National University of Ireland in Galway. Assembled by Dr. Jason King, the Annals describe the horrors that the nuns witnessed and experienced that summer.

According to the Annals: “Hundreds of people were laying there, most of them on bare planks, pell-mell, men, women and children. The moribund and cadavers are crowded in the same shelter, while there are those that lie on the quays or on pieces of wood thrown here and there along the river.”

Mother Superior McMullen assembled her sisters to point out the stark task ahead of them in caring for the unfortunate souls in the fever sheds. Visibly shaken, she told her underlings: “Sisters, the plague is contagious. In sending you there, I am signing your death warrant, but you are free to accept or refuse.” Having taken Catholic vows, the nuns all accepted the assignment and immediately went to the fever sheds to care for the sick and the dying.

In the horrifying stench of the ramshackle structures, they found dying patients moaning in pain and begging for water. The filthy quarters were shared by the living and the dead, with crying orphans still clinging to deceased parents.

The nuns did their best to care for the sick, but soon they too caught typhus and seven of them died. They were replaced by the Sisters of Providence, who were in turn replaced by the Sisters of the Hotel-Dieu. Priests also came to offer blessings, hear confessions and hold services, at great personal risk.

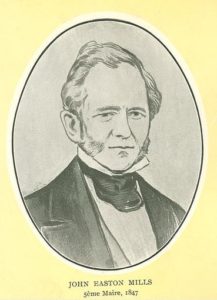

The newly-elected Mayor, a handsome and compassionate American named John Easton Mills, sprang into action. He ordered the construction of a dozen new fever sheds just across the canal in the vicinity of the Wellington Street Bridge. Coffins were piled up near the sheds and the dead were “trenched” at night, with up to 2 dozen being interred in burial trenches every 24 hours.

Citizens began to worry after spotting an emaciated girl, clad only in a nightgown, with a tin cup on the corner of McGill and Notre-Dame Streets.

They called the police to remove her to the fever sheds. Montreal’s citizens were terrified that the typhus would spread. When the disease began to appear throughout the city, an angry mob assembled on the Champ-de-Mars and threatened to throw the fever sheds and their victims into the Saint Lawrence River.

The Mayor urged restraint and tried to calm the citizens with new measures. A fence went up around the landing site and policemen stood guard at the gate to prevent infected emigrants from roaming into the city. The canal itself formed another barrier and guards were posted on all the bridges to further isolate new arrivals.

The Mayor also ordered the sheds to be moved further away from the city – to a place about a mile down-shore in Point Saint Charles called Windmill Point. Twenty-two more fever sheds were constructed to serve the victims and another grim burial ground was prepared on the west side.

As the death toll mounted, more trenches were dug and typhus victims were buried unceremoniously in the middle of the night.

Finally, Mayor Mills personally volunteered to care for the sick and dying emigrants and could often be seen at the midnight hour, going from shed to shed, offering water and hope to patients, allowing doctors and nurses some much needed rest.

With the cold of the autumn, the typhus began to retreat from Montreal and the survivors either moved westward down the canal, or for those with no means, moved into Griffintown.

The death toll was staggering: in addition to the 6,000 Irish victims, almost 1000 Montreal residents, at least 8 Catholic priests, thirteen nuns, and seven Anglican clergymen also perished from typhus.

The Mayor dropped out of sight and citizens began to wonder what had happened to him. It turns out that Mayor Mills contracted typhus himself during his duties. According to his doctor, he never issued a word of complaint about the pain or his misfortune. He died on November 12, at the young age of 54. An elaborate funeral was held and he was declared “Montreal’s Martyr Mayor” for his heroic efforts.

Black ’47 would be remembered as a major injustice against Irish people in Montreal. As the years began to pass, the cemetery became overgrown and weed-choked, with only a small mound and a cross to mark the spot.

In 1854, the old fever sheds were converted into housing by Peto, Brassey and Betts, the British firm responsible for building the Victoria Bridge. The site was soon bustling again when up to 500 English and Irish bridge workers moved in. The adjacent cemetery was seen as a sacred spot, no doubt since many of the laborers were Irish Famine survivors and had relatives buried there.

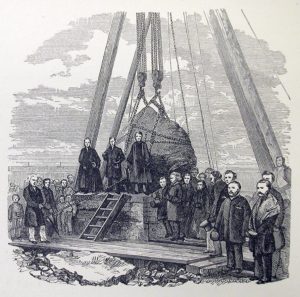

In the autumn of 1859, the Victoria Bridge was nearing completion. When human remains were accidentally unearthed, workers became so concerned that the remains of their poor countrymen would be forgotten that they decided to erect a monument upon the spot. According to legend, the Irish Catholic workers refused to continue working until the victims of Black ‘47 were commemorated.

The monument took the form of a gigantic, 30-ton granite boulder that was pulled up from the riverbed. On December 1, 1859, chief engineer James Hodges oversaw the Herculean business of installing the enormous, rough monument in the cemetery. He arranged a derrick to hoist the boulder onto a six-foot stone pedestal, where it was affixed.

On the same day, the Anglican clergy oversaw a dedication ceremony. The fact that Catholic authorities were not invited to consecrate this important cemetery, containing mostly Irish Catholic Famine victims, rankled the Irish community. During the ceremony, Anglican Bishop Fulford promised that the bodies of the faithful would “rest undisturbed until the day of resurrection.”

In 1870, the memorial grave site was transferred from Messrs. Peto, Brassey and Betts to the Anglican Bishop of Montreal, in perpetuity. Redemptorist priests began organizing annual visits to the gravesite in the mid-1880s to perform requiems “for the repose of the souls of the thousands of Irish Catholics whose bones are there interred.” In 1892, the Montreal chapter of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) was founded and took over organizing the annual march with a mandate “to protect the welfare of fellow Irish Catholics.”

The cemetery began to fall into a state of neglect and The True Witness and Catholic Chronicle complained that “the tall, tangled grass and the sturdy weed riot luxuriantly over the neglected plot where man’s feet seldom stray.’

The following year, the Anglican Bishop was approached by the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) because the company wanted to purchase the Famine cemetery to expand railway operations.

Upon hearing the news, the Irish community became incensed and stakeholders vowed “to prevent by every means in their power the carrying out of such a project.”

With tensions mounting, in the early morning on December 21, 1900, the GTR did the unthinkable: its workers removed the Irish Stone from the Famine cemetery and transported it on a railway track to Saint Patrick’s Square, beside the canal, where it was installed. The Irish community was outraged and demanded the return the monument to its proper location.

By now, industrial work carried out by GTR was beginning to compromise the cemetery. The company had laid down three railway tracks and was using part of the cemetery as a dumping ground. GTR refused to replace the monument, and began to publicly refute the fact that the site was indeed a cemetery. The case was referred to the Railway Board of Commissioners in Ottawa, which ruled in January of 1911 that GTR could expropriate the entire site of the burial ground apart from a small, thirty foot plot of land. The Irish Stone was returned to its proper location, albeit on a much smaller cemetery footprint.

While Montreal’s Irish community continued to host commemorative events and annual marches, the forces of industrialization would relentlessly encroach upon the hallowed Famine cemetery, again and again.

In August, 1942, workers engaged by the Kennedy Construction company made a ghastly discovery while digging a passenger tunnel under the city approach to the Victoria Bridge. They unearthed twelve “coffins of rotting pine wood, blackened by time, in a long trenchlike grave at the foot of Bridge Street. The Irish community reburied the deceased at the site of the monument, in plain grey caskets, during an All Saints Day ceremony on November 1, 1942. The discovery put to rest any denial that the site was, in fact, a cemetery.

A new threat to the cemetery was perceived during construction work for Expo ’67. By now, the Irish Stone had been blackened by a century of traffic and was often referred to as the “Black Stone”. In the spring of 1966, Montreal urban planners decided that the Stone needed to be moved from its existing position to allow the construction of a new approach road to the Expo site. The Irish community insisted that the Irish Stone remain in its place. An unhappy compromise was reached when both parties reluctantly agreed on a “split-solution”: Bridge Street would be expanded around the Irish Stone, leaving the monument on a traffic island. The Irish community had prevented the monument’s removal for a second time, but the fact that a busy highway now surrounded the memorial site was seen as far from ideal.

During the 1990s, to mark the Famine’s 150th anniversary, commemorative monuments were erected around the world. In an effort to improve the site of the Irish Stone, the United Irish Societies launched a successful campaign to decorate the fence surrounding the memorial site with 128 now-rusting shamrocks. A nearby road, which passes by the site where 22 fever sheds once stood, was baptized Rue des Irlandais.

In 1994, the City offered to create a fenced in viewing area on the east side of Bridge Street, which the Irish community gladly accepted. A plaque was installed with the following words:

“In 1847, six thousand Irish people, seeking refuge in a new land, died here of typhus and other ailments, and were buried in mass graves. The stone marks approximately the centre of the cemetery. Immediately to the east of here, twenty two hospital sheds had been constructed. Many Grey Nuns, several priests, and also John Easton Mills, Mayor of the City of Montreal, who selflessly came to care for the sick, themselves contracted typhus and died. May they rest in peace.”

Despite these improvements, there were concerns that more could be done to improve the site. In 2014, the Montreal Irish Monument Park Foundation was established to propose a world-class cultural and memorial park. The Foundation proposes honouring the key players during Black ’47, including the 6,000+ victims, the Montrealers who went to the aid of the emigrants, including Mayor John Easton Mills, and the French Canadians who adopted Famine orphans. Indeed, today an estimated 40% of Quebeckers have Irish roots.

The Foundation has since worked tirelessly lobbying different levels of government and other stakeholders to assist in this process. For a while, it appeared as though progress was being made, but in May, 2017, the land was suddenly sold to Hydro-Québec to build a new electricity distribution station. The Irish community was once again outraged, prompting Hydro-Québec to agree to use part of the land to establish the desired memorial park.

Since then, Hydro-Québec has been busy conducting an archaeological study. On Tuesday, October 10, 2017, Hydro started digging a series of test holes at the site, a legal requirement to check for soil contamination.

Victor Boyle, in his capacity as Canadian President of the AOH, organized to have a local Irish Catholic priest present as this work started. Father McCrory, assigned to St. Gabriel’s Parish in Point St. Charles, took charge of the ceremony. As the majority of the 6000 victims buried in the area in 1847 were both Irish and Catholic, the Good Father blessed the site, the workers, the soil, the machinery and the task at hand so as not to disturb the Irish dead. The workers, moved, turned off the machines and one of them removed his hard hat, solemnly declaring: “My grandmother was Irish.”

Irish Monument Park Foundation Director Fergus Keyes said at the time:

“We certainly have to take a moment to mention that the company doing these tests seems to be called GHD – likely a contractor for Hydro – and the guys working were absolutely terrific. Couldn’t have possibly asked for more co-operation. They shut down their machinery so Father could give his blessing and mentioned that in all the years that they have done this work, they had never been blessed before and seemed pleased with the small ceremony. So thanks to Father McCrory, Victor Boyle and the workers on the site – it just seemed like the right thing to do as they drill into the ground. We don’t really suspect that any sign of the victims will be uncovered, but with 6000 buried there; and the haphazard fashion that the burials were conducted – particularly in the late fall of 1847 – one never knows.”

While nobody knows what the future holds for the site yet, the community is hopeful that Famine cemetery marked by the Black Rock will finally be commemorated in a fitting and respectful manner.

To this day, every year on the last Sunday in May, the Irish community marches to the Black Rock under the leadership of the AOH. Speeches are delivered and the community takes a moment to solemnly remember the Famine dead. The experience can only be described as haunting.

According to AOH President Victor Boyle, “When you touch the Black Rock, it is always warm. It has a texture unlike any other stone I’ve ever touched. It doesn’t feel like a rock. It almost feels like something is coming through it.”

He then added: “When I was touching it once, I remember leaning against it and getting a feeling of life. It was a spooky feeling, almost like underground roots were holding up the Irish Stone. The people buried there don’t want to be forgotten. They can’t talk. It bothers me that the Black Rock was cut off when the road was built around it. Those buried here are crying out because they can’t participate. They don’t like it because they are cut off. It’s a curse.”

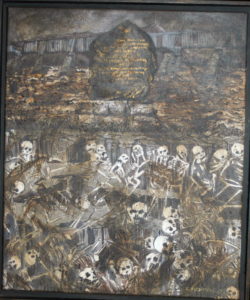

A painting by Karen Bridgenaw of the Group of Sven Painting Ladies captures the haunted mood that exists at the Black Rock very nicely.

For those wishing to experience the commemoration, the 2018 Walk to the Stone is scheduled on May 27, beginning at noon at St. Gabriel’s Church in Point St. Charles.

It is an incredibly moving event, a dark reminder for Montrealers of just how much the tragic episode of Back ’47 continues to haunt the city to this very day.

COMPANY NEWS

Haunted Montreal is currently in winter mode, meaning there will be no more public ghost tours until May, 2018. Private tours are still available for groups of 10 or more people, subject to the availability of our actors and weather conditions.

Haunted Montreal has been contacted by a media production company because they wish to do an episode about ghosts and hauntings in Griffintown. Based in the United Kingdom, the company has requested Haunted Montreal’s assistance in finding people to appear on the television program to share their personal ghost story from the Griff. Shooting will take place from May 16-18, 2018.

If you have a Griffintown ghost story or paranormal experience to share and are willing to appear on television, please contact us at info@hauntedmontreal.com

Haunted Montreal would like to thank all of our clients who attended a ghost walk during the 2017 season! If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page, something that helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours. Lastly, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list.

Coming up on April 13: The Victorian Ghost of Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue

Sometime around 2010, two women were visiting the quaint little town of Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue, at the western tip of Montreal Island. After visiting a secondhand book shop, they both spotted an adolescent girl dressed completely in white, complete with an old Victorian-style dress, white hair ribbons, white stockings and white shoes. Nobody else seemed to notice the strange girl on the street, who was walking very quickly towards the bridge that connects to Ile Perrot. When the women drove away, leaving the weird scene behind, they were shocked to see exact the same girl some distance up the road, ready to start her walk all over again. With other verified sightings, people are starting to wonder just who the Victorian ghostly girl is and why she is haunting Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue.

Donovan King is a historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbot College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec).

You should mention if you can, mention that the Stokestown foundation, is planning to be involved in the March to the Rock on May 27 and are planning to do a show on descendants of famine victims.

You can get further details from Dr. J KIng

Ps this history of THE BLACK ROCK is extremely well written. I found it facinating

A spectacularly informative historical article! I enjoyed it tremendously. Thank you Donovan!

Sincerely,

Cheryl Nye

Thank you for your kind words Cheryl!