This month we provide an update on the Hôpital de la Miséricorde and analyze controversial plans by Hydro-Québec to integrate an electricity substation into the haunted site. The ghost-ridden Hôpital de la Miséricorde has been empty for years and is starting to crumble. Located on prime real estate in Downtown Montreal...

Welcome to the eighty-first installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog!

With over 500 documented ghost stories, Montreal is easily the most haunted city in Canada, if not all of North America. Haunted Montreal dedicates itself to researching these paranormal tales, and the Haunted Montreal Blog unveils a newly researched Montreal ghost story on the 13th of every month!

This service is free and you can sign up to our mailing list (top, right-hand corner for desktops and at the bottom for mobile devices) if you wish to receive it every month on the 13th! The blog is published in both English and French!

Haunted Montreal is pleased to announce that we are offering our regular ghost tours every Saturday evening on rotation up until June, when the season will be expanded:

Haunted Griffintown Ghost Walk

Our Haunted Pub Crawl is offered every Sunday at 3 pm in English and on the last Sunday of the month at 4 pm in French.

While public tours are available Saturday nights and Sunday afternoons for the Haunted Pub Crawl, private tours can be booked at any time based on the availability of our actors.

Our Virtual Ghost Tour is also available on demand!

Additionally, our team is releasing videos of ghost stories from the Haunted Montreal Blog every Saturday, in both languages!

Our hosts include Holly Rhiannon (in English) and Dr. Mab (in French).

Want to give the gift of a haunted experience for the 2022 season?

You can now order a Haunted Montreal Gift Certificate through our website. They are redeemable via Eventbrite for any of our in-person or virtual experiences. There is no expiration date.

Lastly, we now have an online store for those interested in Haunted Montreal merchandise. More details are below in our Company News section!

This month we explore the Fort de la Montagne, the first Residential School in what is now modern-day Canada. Today, only two towers of the old fort remain – and they are reputed to be haunted.

Haunted Research

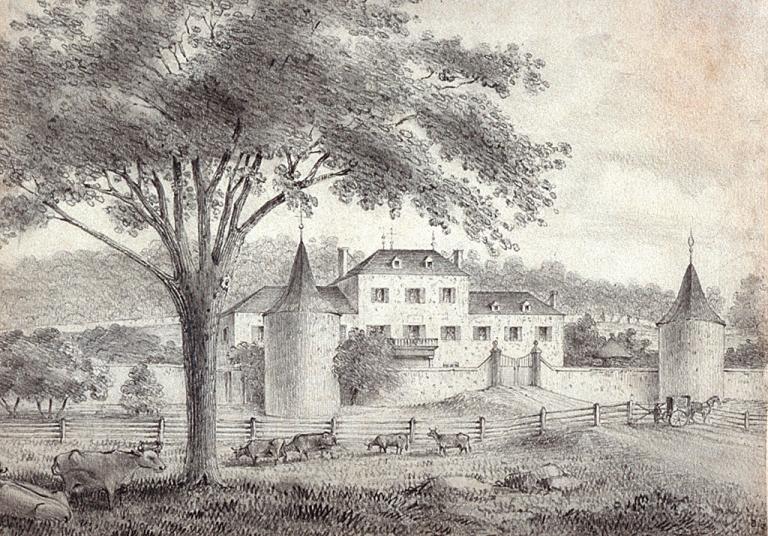

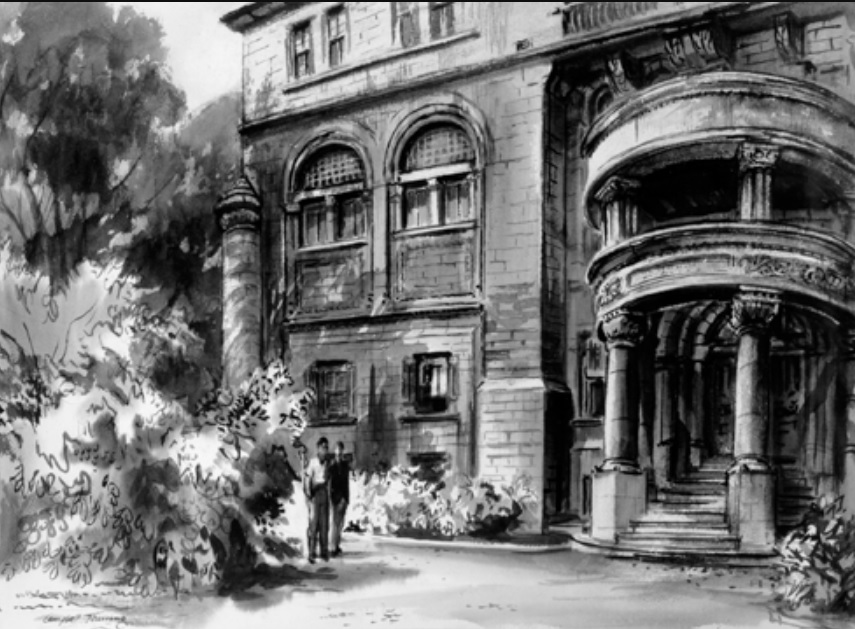

Lurking behind stone walls on Sherbrooke Street stand two old towers that are reputed to be haunted. As some of the oldest intact structures in the City of Montreal, these fortifications have a deranged history.

Designed as the first Residential School in what is now modern-day Canada, the towers actually feature gun-ports. This military architecture was designed to repel anyone – at gunpoint – who might dare to interfere with the “instruction” happening within the fortified “school”.

Before examining these haunted towers, it is a good idea to look at the history that led to their construction.

When Europeans began colonizing the world in the 1500s, their goal was generally to subjugate Indigenous civilizations in order to steal their lands and resources. This usually involved cultural genocide, or attempts to extinguish Indigenous practices, beliefs, languages and cultures.

When explorer Jacques Cartier arrived from France in 1534, he planted a 30-foot cross in today’s Gaspé region – to claim all of the indigenous territories on behalf of the King of France, François I.

Indigenous leaders, such as Donaconna, objected to Cartier’s gesture and would later tear down the cross.

Regardless, in the early 1600s, the French began establishing colonies in what they called “New France”. Settlements like Port Royale, Tadoussac, Quebec City and Trois-Rivières began to take shape.

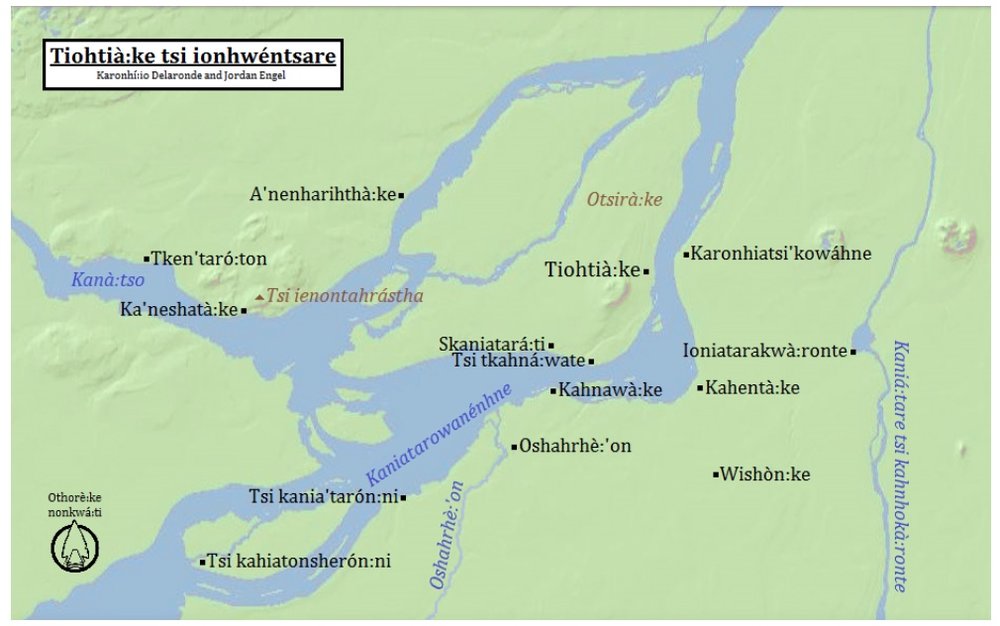

Tiohti:áke, the original Mohawk name for Montreal, was seen as a colonial prize worth taking due to its geographic location. With several rivers systems flowing into the archipelago, the island was a major transportation hub and Mohawk trade center.

However, the French were at war with the Mohawk First Nation along with the rest of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. This league of five allied nations also included the Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida and Onondaga. French authorities saw Tiohti:áke as too dangerous for colonization.

Meanwhile, back in France, in La Flèche, a devout Catholic and tax collector named Jérôme Le Royer de la Dauversière claimed that he had been receiving Holy visions for six years. In these episodes, God instructed him to found a religious colony and a hospital on Tiohti:áke.

Along with other Catholics, de la Dauversière founded “The Notre-Dame Society of Montreal for the Conversion of the Savages of New France” (Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal pour la conversion des Sauvages de la Nouvelle-France) in 1639.

The goal of this colonial organization was to create a “New Jerusalem” on the island -and to convert all Indigenous people to Catholicism.

This evangelical project was related to another one that started in 1637 in Sillery, near Quebec City.

Sillery was the first reserve created by Europeans for Indigenous peoples in what is now Canada. It was funded by a French nobleman, Noël Brûlart de Sillery, in response to an advertisement placed by Father Paul Le Jeune in the Jesuit Relations. Le Jeune was looking for a suitable place to attempt to convert Indigenous people to Catholicism.

His aim was to instill an agricultural lifestyle in the semi-nomadic Algonquin and Innu people of the area to evangelize them. French authorities established the land as a seigneury for Indigenous people under Jesuit supervision.

The project was a total disaster. By the 1670s, epidemics such as smallpox had wiped out many of the Indigenous residents. Unhappy with the deadly diseases, strict Catholic doctrine, and un-arable lands, the last Indigenous peoples had left Sillery by the late 1680s.

Returning to “The Notre-Dame Society of Montreal for the Conversion of the Savages of New France”, their leaders hatched a plan to colonize Tiohti:áke. After a fundraising campaign, they recruited French military officer Paul de Chomedey, sieur de Maisonneuve to lead the project.

On May 17, 1642, de Maisonneuve and his colonists arrived at Tiohti:áke and established the colony of Ville-Marie. Needless to say, this sparked an all-out war between the French and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, who attempted to defend this part of the vast Mohawk territory. The brutal war would last, on and off, until a peace treaty was signed in 1701.

In 1652, while visiting France, de Maisonneuve recruited nun Marguerite Bourgeoys to become Ville-Marie’s first teacher. He envisaged her educating French children and evangelizing Indigenous people, young and old. He also brought over another 100 colonists to bolster the colony during the war.

In April 1658, de Maisonneuve provided Bourgeoys with a vacant stone stable to serve as a schoolhouse for her pupils.

She taught the children of the colony about the Catholic faith, as well as counting, reading and writing. The older girls learned household skills to prepare for marriage and motherhood.

Before long, the stable was deemed too small so another school was constructed. Bourgeoys also started to receive some Indigenous children whom she tried to indoctrinate.

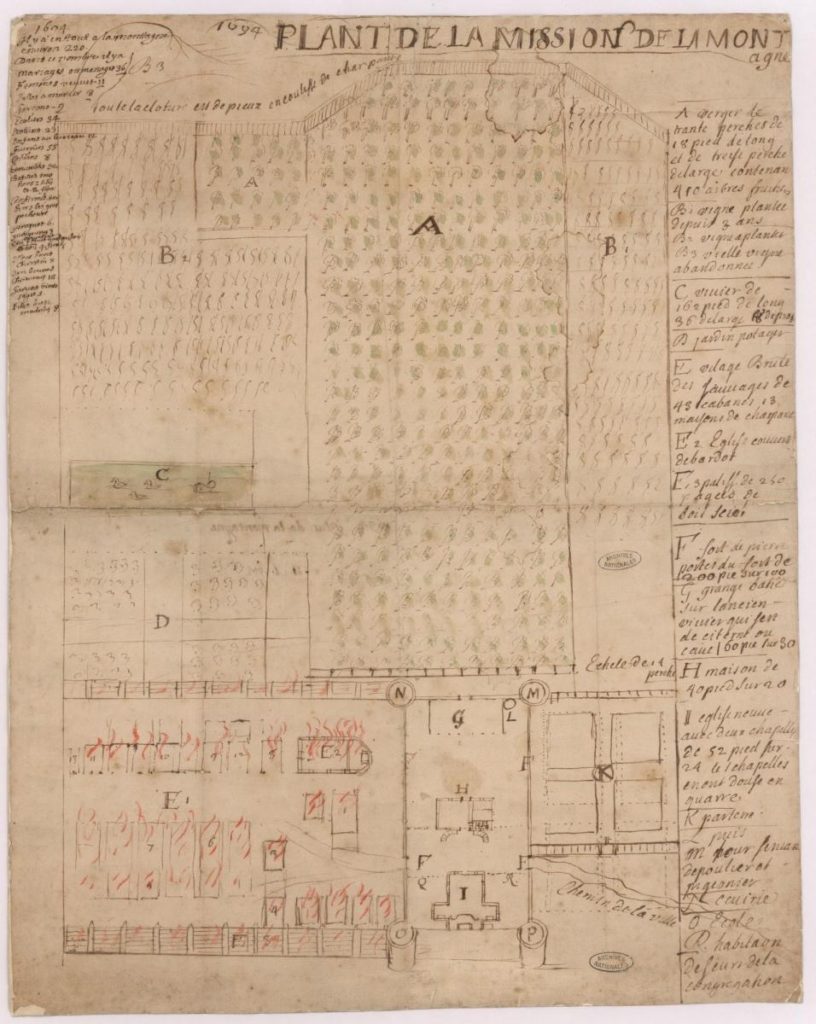

In 1675, a new school called the Fort de la Montagne was established at the base of the mountain.

The purpose of this new institution was specifically to evangelize Indigenous people. The pedagogy was designed ensure their adherence to the Catholic religion, which made up a large part of the curriculum.

However, soon Marguerite Bourgeoys and other authorities noticed that many of the Indigenous students at Fort de la Montagne were practicing traditional culture including ceremonies. Alarmed and upset, the Catholic overseers began describing these practices as “witchcraft”.

Furthermore, in the tradition of Jérôme Le Royer de la Dauversière, certain members of the Catholic community began claiming that they too were receiving direct and visionary messages from God. The highest religious authorities in the colony frowned upon this type of talk, as they could not control it.

As things at the Fort de la Montagne got more and more out of control, word reached the head of the Sulpician Order in Paris, France. In response, a hardliner named François Vachon de Belmont was deployed from Paris to the Fort de la Montagne in 1680 to stop the spread of “witchcraft” and visions.

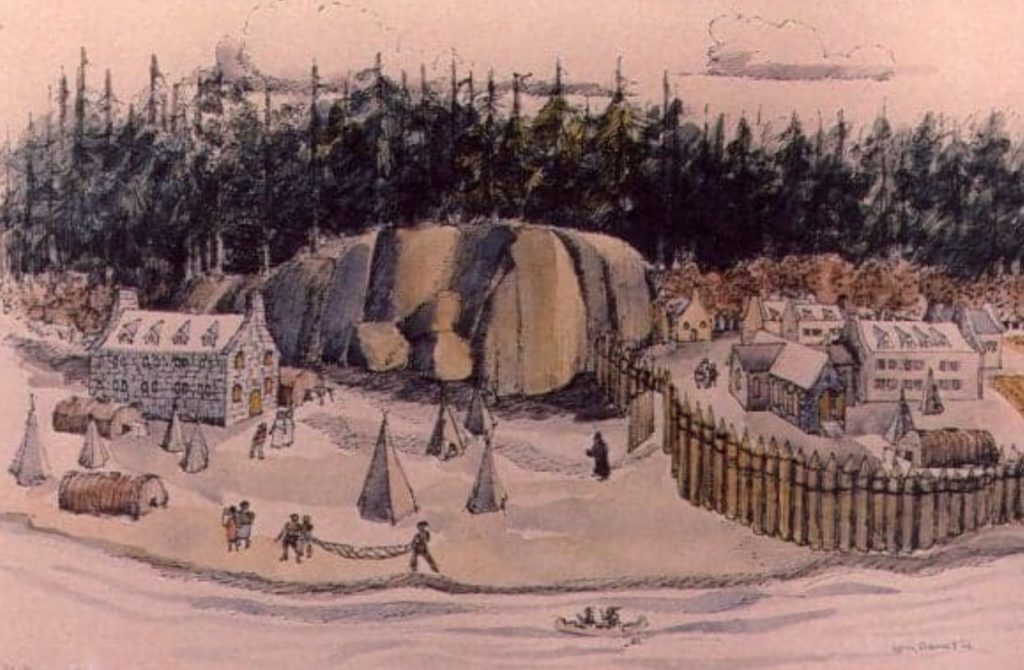

The following year, de Belmont was named as the Superior of the Fort de la Montagne mission, which at that point housed over 200 Indigenous people, mostly Nipissing, Kanienkehà:ka (Mohawk), and Algonquin children, who were living in cabins on the site.

In order to stamp out the “witchcraft”, it is likely that Marguerite Bourgeoys added ghostly Catholic stories to her curriculum. Apparently, one of her favorites was the deranged tale of Jean Saint-Père’s Talking Head.

Ironically, Marguerite Bourgeoys and other Catholics did not consider the decapitated head of a colonist blabbering away after Death to be “witchcraft”. However, they considered traditional Indigenous culture that had been practiced for thousands of years as the Devil’s work.

To further secure the site, in 1685 de Belmont ordered that fortifications be constructed. Colonial workers constructed a 13-meter palisade and four stone towers with ominous gun-ports around the school.

With these new defenses, Indigenous people who tried to rescue their colleagues in the Fort de la Montagne could be shot as they approached the school.

Despite these efforts, Marguerite Bourgeoys and de Belmont were unable to extinguish Indigenous culture within the Fort de la Montagne.

Things exploded in 1689 the day after the Feast of the Dead. On the night of November 3rd, Marguerite Tardy, sister of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame claimed she had a vision from God as she watched by the fireside.

She told Marguerite Bourgeoys that a sister “dead for more than sixteen months” had appeared to her. The dead nun told Sister Tardy: “I am sent from God. Tell the Superior of the Congregation that she is in a state of mortal sin, because of a Sister whom she named to her”.

Given that Marguerite Bourgeoys had founded the Congrégation de Notre-Dame – and was the Superior – this allegation especially alarmed her.

It got worse the following year, when Sister Tardy and a man named Joseph de la Colombière claimed to have experienced new divine visions and appearances.

On the night of January 3rd 1690, Sister Tardy told Marguerite Bourgeoys that she had again received a visit from the deceased nun. This time, the message was more threatening: “This Superior has not yet done what she must do. This is the last time I will warn her…”

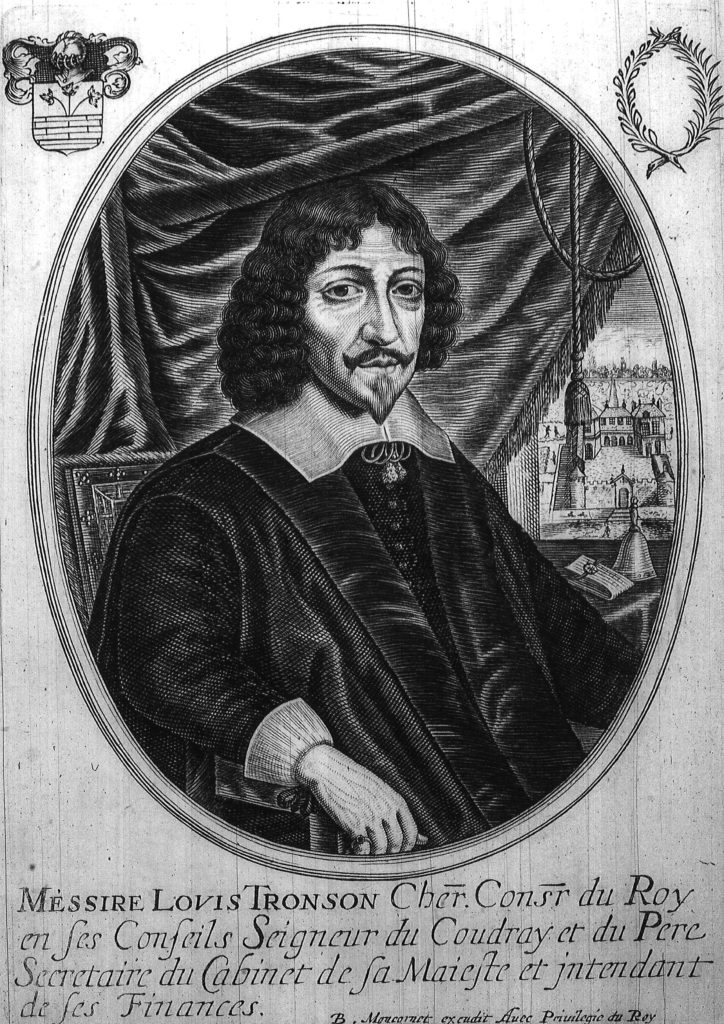

François Vachon de Belmont felt that he was losing control, so sent letters to his superior in Paris, Louis Tronson, explaining the situation.

Louis Tronson was very surprised to learn the extent of the affair. He reacted quickly to snuff out the so-called “visionaries” before their claims could spiral out of control. He was especially worried that people like Sister Tardy and Joseph de la Colombière could cause scandal all the way to the King’s court.

For Louis Tronson, these supernatural manifestations were only “chimerical visions” and “ridiculous prophecies”. He described the visions as “the production of a hollow head and a heated imagination”. He charged the culprits with having “visible errors” and said they were “deceived by their false views”.

To break the chain of the conspiracy and to destroy its influence, Tronson recalled all malcontents back to France. These included Sister Tardy, Joseph de la Colombière and a priest named William Bailly.

Once the Catholic rebels had been deported, Louis Tronson demanded the absolute submission of the Sulpicians to their Montreal Superior. Anyone who did not comply with Tronson’s orders were threatened to be sent back to France.

In September 1694, a major fire broke out at the Fort de la Montagne.

A young warrior fired a gun into the cabin of an adversary. The occupants had time to flee, but the fire caught and spread quickly due to high winds.

Within three hours, nearly fifty Indigenous cabins, fifteen frame-houses, the Church and much of the palisade surrounding the village had all burned to the ground.

By 1696, the Indigenous inhabitants had been relocated to the other side of the island, to Fort Lorette at Sault-au-Recollet. In 1721, the mission was finally relocated to present-day Kanesetake.

In 1854, during the building of the College of Montreal, all of the remains of the Fort de la Montagne were demolished expect for the two southern towers. They still stand today.

Originally, the west tower had housed the school of Marguerite Bourgeoys. The nuns of the Congregation used the east tower as a chapel. Today, both towers are empty – and for good reason. They are both reputed to be haunted.

Students at the College of Montreal often dare each other to visit the haunted towers at midnight. There have been many reports over the years that visitors to the West Tower sometimes hear the sounds of children weeping emanating from the gun-ports.

One former student reported to Haunted Montreal that she had visited the towers with some fellow students one Friday the 13th in 2018. She explained:

“We decided to go on a dare. During the daytime, the towers, while creepy-looking, don’t exhibit much paranormal activity. According to the legend, midnight is the best time to go to experience the hauntings. When midnight struck, we decided to start with the West Tower.”

As they crept up to the imposing fortification in the darkness, one of her friends dared her to approach a gun-port and shine her flashlight inside.

Nervously, she approached until she was mere feet away. She claimed:

“Just as I was about to shine my light into the tower’s gun-port to see what was inside, I heard a loud burst of sobbing coming from inside! I was so taken aback that I literally fell over! As I tried to scramble back to my friends, I heard a softer weeping sound, almost like children. My friends had already run away in terror and once I picked myself up, I ran away also. It was one of the most frightening nights of my life!”

The East Tower is also reported to be haunted by a ghostly nun. Her apparition has been spotted standing outside the heavy door of the structure, as though awaiting others to follow her inside.

According to lore, she appears at night and sometimes beckons those exploring the site to join her inside with a hand gesture. She then turns around and walks straight through the thick wooden door, effectively vanishing.

Many speculate that the ghost is that of Sister Marguerite Tardy. Some believe she returned in the afterlife due to her failure to convince authorities of her visions and subsequent deportation to France.

The towers were designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1970 and as provincial historical monuments in 1974.

Today, despite running the first Residential School in modern-day Canada, Marguerite Bourgeoys is celebrated like few others.

Marguerite Bourgeoys became Canada’s first female Saint on Hallowe’en in 1982, when Pope John Paul II canonized her at Vatican City. There is also a French school board named after her, a museum about her life in the Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours Chapel, not to mention a stamp in her honour and various other commemorations across the country.

People can also visit her final resting place in the Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours Chapel in Old Montreal, which is also said to be haunted.

In conclusion, despite the fact that Marguerite Bourgeoys and the Fort de la Montagne were instrumental in cultural genocide against Indigenous people, they have both been immortalized and glorified by Church and government officials. Perhaps this is one of the reasons the towers are said to be haunted.

In the Age of Truth and Reconciliation, perhaps it is time to re-evaluate the discourse surrounding the first Residential School created by European colonists.

It was, after all, the progenitor of all of the others to come. Instead of celebrating and glorifying these symbols of cultural genocide, it might be best to re-contextualize them historically in a more realistic light.

Visit these haunted towers at your own risk, especially during the witching hour!

Company News

Haunted Montreal is pleased to announce that we are offering our regular ghost tours every Saturday evening on rotation up until June, when the season will be expanded:

Haunted Griffintown Ghost Walk

Our Haunted Pub Crawl is offered every Sunday at 3 pm in English and on the last Sunday of the month at 4 pm in French.

While public tours are available Saturday nights and Sunday afternoons for the Haunted Pub Crawl, private tours can be booked at any time based on the availability of our actors.

Our Virtual Ghost Tour is also available on demand!

For private tours, clients can request any date, time, language and operating tour. These tours are based on the availability of our actors and start at $170 for small groups of up to 7 people.

Email info@hauntedmontreal.com to book a private tour!

Furthermore, our team is releasing videos every Saturday, in both languages, of ghost stories from the Haunted Montreal Blog. Hosted by Holly Rhiannon (in English) and Dr. Mab (in French), this new initiative is sure to please ghost story fans!

Please like, subscribe and hit the bell!

In other news, if you want to send someone a haunted experience as a gift, you certainly can!

We are offering Haunted Montreal Gift Certificates through our website and redeemable via Eventbrite for any of our in-person or virtual events (no expiration date).

Finally, we have opened an online store for those interested in Haunted Montreal merchandise. We are selling t-shirts, magnets, sweatshirts (for those haunted fall and winter nights) and mugs with both the Haunted Montreal logo and our tour imagery.

Purchases can be ordered through our online store: shop.hauntedmontreal.com

Haunted Montreal would like to thank all of our clients who attended a ghost walk, haunted pub crawl, paranormal investigation or virtual event during the 2021 season!

If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page, something that really helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours.

Lastly, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list.

Coming up on June 13th: The Haunted Cross on the Mountain

Visible from 80 kilometers away, Montreal’s 30-meter high metal cross on the mountain glows at night with special lighting. A symbol of Catholicism, it was based on a wooden cross that French colonists erected in 1643. To prevent any interference, the cross is surrounded by metal fencing and has sensors and video cameras to alert the police to any intruders. Today, rumours are swirling that the site of the cross is haunted because the mountain is peppered with Indigenous graves dating back thousands of years. A group called the Mohawk Mothers is now calling for its removal as a symbol of genocide.

Author:

Donovan King is a postcolonial historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbott College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec). He is also a certified Montreal Destination Specialist.

Translator (into French):

Claude Chevalot holds a master’s degree in applied linguistics from McGill University. She is a writer, editor and translator. For more than 15 years, she has devoted herself almost exclusively to literary translation and to the translation of texts on current and contemporary art.

Comments (0)