This month we provide an update on the Hôpital de la Miséricorde and analyze controversial plans by Hydro-Québec to integrate an electricity substation into the haunted site. The ghost-ridden Hôpital de la Miséricorde has been empty for years and is starting to crumble. Located on prime real estate in Downtown Montreal...

Welcome to the twenty-sixth installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog! Released on the 13th of every month, the June 2017 edition focuses on research we are carrying out into a haunted British fort on Saint Helen’s Island. Haunted Montreal is also pleased to announce that our public season is now in full operation, with ghost tours in Griffintown and on Mount Royal alternating every Friday night!

HAUNTED RESEARCH

St. Helen’s Island juts out of the swirling and tumultuous waters of the St. Lawrence River, just to the south-east of Old Montreal. The storied outcrop has a remarkable history, including one site that attracts the most hardened paranormal investigators. Perched on a slope in the middle of the north part of the island looms a creepy old British fort that has long been reputed to be haunted.

Today the fortified structure houses the Stewart Museum, which “celebrates the influence of European civilization in New France and North America.” With noteworthy exhibitions and thousands of historic artifacts, the museum attracts large crowds of visitors each year. While most guests seek a historical lesson at the museum, some of them search for something entirely different: the ghosts and paranormal activities that are said to plague the old fort.

Before examining the fort’s hauntings, paranormal activities and ghost-hunters, a history of the island is in order.

St. Helen’s Island has volcanic origins and its three small peaks rise 30 meters out of the swirling waters of the St. Lawrence River. Approximately 200,000 years old, the island measures 3 kilometers by 600 meters. It has been used by various First Nations people for thousands of years, as evidenced by archaeological discoveries at two sites on the island. Pottery fragments and ancient, broken smoking pipes suggest the island was frequented by the Saint Lawrence Iroquoians, a First Nation that has since mysteriously disappeared.

During Jacques Cartier’s voyage of exploration in 1535, he landed on what is now known as Montreal Island but he failed to mention its tiny cousin, today’s St. Helen’s Island.

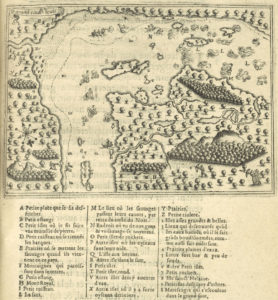

It wasn’t given a European name until 1611, when it was visited by Samuel de Champlain. Admiring the island’s natural beauty, he decided to name it in honour of his pubescent 13 year old wife, Hélène de Champlain. Just a year earlier she had been given in marriage to Samuel de Champlain, who was 31 years her senior.

Given that she had not yet reached the age of consent, a clause in the marriage contract required a lapse of two years before the couple could cohabitate. St. Helen’s Island appears on a map he drew at the bottom, in the middle of the St. Lawrence River.

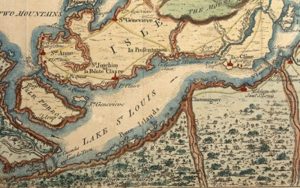

The island witnessed several deaths during the early years of French colonization. On June 5, 1611, A Montagnais leader named Outetoucos and a French colonist named Louis drowned while attempting to shoot the swirling rapids after hunting for heron on a nearby island. Outetoucos was buried on St. Helen’s Island whereas Louis’ death would go on to influence Montreal’s toponymy. The turbulent waters where the men drowned were named Sault-Saint-Louis Rapids and, further to the west where the river widens, the body of water was named Lake St. Louis, in honour of the drowned Frenchman.

The island saw death again on August 9, 1664, when French colonists Jacques Dufresene and Pierre Maignant were killed by Iroquois warriors. Following the establishment of the Ville Marie colony on Montreal Island in 1642, a state of war broke out between the local Mohawk First Nation and the French colonizers, who were attempting to convert them to Catholicism.

The first record of ownership of the island dates back to 1635, when the Company of New France granted the Seigneury of Citiere, which included St. Helen’s Island, to Francois de Lauzon, the governor’s son. In 1657, de Lauzon ceded a strip of the seigneury to Charles Le Moyne, including St. Helen’s and Ronde islands. Remarkably, in 1700 the King of France designated Charles LeMoyne as a Baron to honour his military achievements, making him the only person born in New France to ascend into the nobility. The Longueuil Seigneury was also declared a Barony, the only one to exist in New France.

In 1760, British soldiers marched on Montreal and the city capitulated, putting an end to the New France project. However, the new British overlords did not dispute the private ownership of lands, so St. Helen’s Island remained in the hands of the Longueuil family in the following years.

The British wanted the island to build a fort on it following the War of 1812, a conflict that saw American militias invading Upper and Lower Canada, albeit unsuccessfully. To better defend Montreal, they wanted to build a fort, powder-house, barracks and blockhouse on the St. Helen’s Island. In 1818, the Baroness of Longueuil authorized the sale of the island to the British government for the sum of £15,000.

The fort was constructed between 1820 and 1824, according to the plans of Lieutenant-Colonel Elias Walker Durnford, an officer of the Royal Engineers. It included an ammunition arsenal, weapons depot, barracks, a small powder house, and a guard house, surrounded by a thick limestone wall. Outside the fortified complex stood a large, bomb-proof powder house which could hold up to 5000 barrels of gunpowder. Designed to serve as an arsenal and storage facility, it was part of a defensive chain of forts built to protect Canada from the threat of an American invasion.

The stone used to build the fort is a mix of red breccia, quarried locally on the island, and grey fieldstones from Montreal’s original fortifications, which were dismantled a few years earlier.

During the 1832-1834, Montreal was hit with a crisis. After a ship arrived carrying infected immigrants, a cholera epidemic began ravaging the city. The fort was pressed into use as a cholera hospital and many of those hospitalized surely died there because the disease is highly contagious and had a death rate often higher than 50%. The epidemic claimed almost 2000 victims in Montreal, killing almost 6% of the inhabitants. It left in its wake devastated, broken families and hundreds of orphans whose parents had succumbed to the disease.

More change was to come. In 1829, a military cemetery was laid out in the eastern part of the island. In 1837, the fort changed vocation again when it was transformed into a military prison following a series of rebellions. It was ravaged by fire in 1848, but was rebuilt from 1863 to 1864. Only four years later, in 1867, the Dominion of Canada was created on July 1st. The British troops left Canada in 1870 and the Canadian government acquired the island and transformed it into a public park in 1874.

The fort was active during both World Wars. During World War I, the fort served as a munitions depot and in the 1930s it was restored as a Depression era job creation project. During World War II, the fort was converted into an internment camp called s/43. POWs in this camp, mostly of Italian and German nationality, were forced to do hard labour, included farming and chopping down trees.

In 1944, the internment camp was closed following the release of an internal report about the mistreatment of prisoners.

The David M. Stewart Museum was founded in 1955, to collect, store and display historical artifacts from Canada’s colonial past, particularly from the era of New France. Established within the fort, the museum’s collections include artifacts dating from the 16th century through to the 19th century.

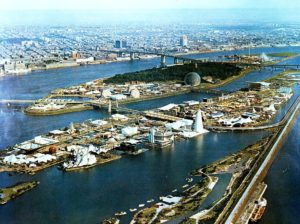

During the 1960’s St. Helen’s Island saw major changes because it was chosen as the site of Expo 67, a World’s Fair on the theme of “Man and His World”. Using 28 million tons of earth excavated from the construction of the Montreal metro, St. Helen’s Island was greatly enlarged and merged with several nearby islands. The adjacent Notre Dame Island was also constructed at this time to host pavilions from over sixty countries for the World’s Fair. From April 27 to October 29, 1967, 50 million visitors attended Expo 67, which is considered to be the most successful World’s Fair of the 20th Century.

After the closing of Expo in late 1967, the site was renamed the Parc des Îles de Montreal. In 1999, it was renamed again, this time Parc Jean-Drapeau in honour of former Mayor of Montreal who had built the Montreal Metro, enlarged the islands, and brought Expo 67 to the city.

Returning to the fort and museum, today they are open year-round. While visitors can enjoy some exceptional exhibitions and activities at the museum, they must also contend with all sorts of paranormal activity.

There are many reports of hauntings at the museum. Strange apparitions have been spotted lurking in the shadows. The sound of phantom boots can be sometimes be heard marching in unison, as though soldiers were marching in formation. Objects are also known to go missing and some visitors complain about feelings of malaise and shortness of breath. Add to this mysterious mists, strange lights, disembodied voices, and the unexplained smell of smoke, and it is easy to conclude that the fort is very haunted.

One box office worker, who is a bit creeped out working at the fort, suggested that there is at least one ghost she is aware of. The spirit is of a quartermaster or cook from long ago, according to the young lady. She heard reports that area where the barrack’s kitchen used to be is haunted. People have smelled a wood fire burning and heard the sound of pots clanging, despite the fact no fire is lit and the area is not used as a kitchen anymore. Staff whisper that the ghost of a quartermaster haunts the site.

The most famous quartermaster to work the military canteen was a gruff philanthropist named Charles McKiernan, also known as “Joe Beef”. After feeding troops during the Crimean War, he was transferred to Montreal in 1864 with his artillery regiment and charged with cooking for the troops stationed at the fort. When he was discharged in 1868, he opened “Joe Beef’s Canteen,” an infamous inn and watering hole located at 201–207 rue de la Commune in what is now Old Montreal.

Hundreds of longshoreman, labourers and seamen frequented the canteen to drink and have a meal. Wealthier clients could have steak and onions for 10 cents, while the poorer patrons received a bowl of soup and hunk of bread for free. The eccentric Joe Beef also kept a menagerie of wild animals in the cellar and two human skeletons behind the bar to entertain guests. Known to dislike authority, he supported striking Lachine Canal workers in 1877 by providing free bread and soup to the picket line. On January 15, 1889 Joe Beef died suddenly of a heart attack. His funeral was one of the most well attended in Montreal’s history. Could Joe Beef’s ghost have returned to haunt the old fort, perhaps to continue thwarting authority?

The haunted fort was also featured on a French ghost investigation program on television called L’Enquêteur Du Paranormal. In an episode entitled Le Fort De l’Île Ste Hélène & La Maison Hanté De Contrecoeur, paranormal expert and host Christian Page, interviewed Laure Pavlovic, the Education Co-ordinator at the museum. She acknowledged that there are many reports of haunted activity and mentioned that security cameras sometimes pick up strange phenomena, such as lights turning themselves on and off. Christian Page also invited three mediums to the fort to try and communicate with its ghosts.

The first medium, Michel Alexandre L’Archevêque, saw a spirit moving quickly near a basement wall and detected the ghosts of young soliders. The second medium, Sylvain Bolduc, heard phantom boots marching and cutlery clinking in the area where the kitchen once existed. He also smelled paranormal smoke and witnessed the ghost of a prisoner in a green shirt who spoke Italian, but not French. This spirit was likely an Italian prisoner in the s/43 internment camp, perhaps one of the inmates who had been mistreated. He also detected the ghosts of children, perhaps the spirits of orphans from the time when it was a cholera hospital. The third medium, Sylvia Davenzo, identified the ghosts of people who had starved to death and others and who were chained up, suggesting they could have originated from the time it was a military prison.

Meanwhile, one persistent rumour that has been circulating on the internet suggests that 800 soldiers were buried in a mass grave on the island after being taken down by sharpshooters.

According to hauntedplaces.org: “Fort de l’Île Sainte-Hélène on Saint Helen’s Island is haunted by some of the 800 soldiers who are buried nearby in a mass grave, victims of enemy sharpshooters.”

Meanwhile, thechive.com reports: “Witnesses report that it is to be home of eight hundred soldiers who lost their lives when their General purposely put them in the line of fire of enemy sharpshooters. They are buried in a mass grave on the island.”

However, a visit to the nearby military cemetery, located to the south-east of the fort, reveals no such nonsense.

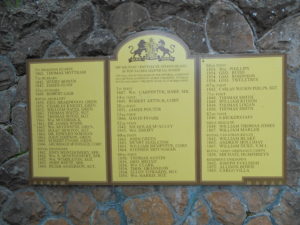

Estimates put the number of bodies in the cemetery at around 100. According to the commemorative plaque in the graveyard, inaugurated in 1935, there are a total of 58 known soldiers and “several others of names unknown” buried from various regiments and brigades. The plaque also informs visitors that “several wives and many children were also buried here”, but there is no mention whatsoever of 800 soldiers buried in mass graves.

Furthermore, according to some sources, the graves were exhumed and the bodies were moved around 1915. Where these unfounded rumours originated and why they were circulated is unknown at this time, but they continue to make the rounds on the internet.

Whatever the case, the curators of the Stewart Museum are not unaware of its ghosts. Indeed, they sometimes celebrate Halloween with a nocturnal event called “Strange and Haunted Objects”. Children aged 7 and up are invited to examine presumably cursed “locks, keys, globes, telescopes, sundials, powder horns, kitchen accessories, antique prints, sculptures, miniature objects, hat boxes and pipe cases,” while hearing “extraordinary tales about objects and ghosts” in the creepy fort.

The sum of all the ghostly rumours, paranormal investigations and strange encounters suggests that the fort on St. Helen’s island is very haunted. With so many stories about ghosts and paranormal activity at the fort and museum, it is no wonder it is such a popular place for mediums, ghost-hunters and curiosity-seekers to visit.

Company News

The Haunted Montreal public season of ghost tours is now open, with Haunted Griffintown and Haunted Mountain being offered in both English and French. In May and June, the two tours will alternate every Friday night. From July to October, Haunted Griffintown will be offered on Friday nights and Haunted Mountain on Saturday nights. There are also many extra tours that have been added on Mount Royal in French due to high demand.

To learn more, please visit our website. It was recently re-done to make it more manageable and user-friendly. With an integrated platform it is easier to navigate the website and blog. The blog has also moved onto the website itself and can now be read in either language in separate areas. Ticket sales have become completely automated and we have added a Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) page.

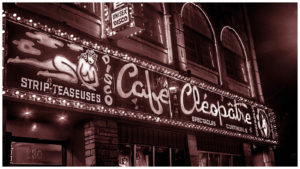

We have been busy helping establish a new company called Secret Montreal! The new company will take over the Haunted Red Light District Ghost Walk and will also offer a brand new Montreal Burlesque Walking Tour that is being led by real burlesque queens!

From June 23 to September 4, the Haunted Red Light District Ghost Walk will be offered in English on Sunday nights, in French on Monday nights and in both languages on Friday nights.

Secret Montreal plans to develop other tours in the future that delve into the city’s fascinating past with a focus on hidden history.

For details on Secret Montreal and its walking tours, please visit the Secret Montreal website.

Lastly, a big thank you to all of our clients who attended a Haunted Montreal ghost walk! If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page, something that helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours. Furthermore, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list.

Coming up on July 13th: Maison Pierre du Calvet

The Maison Pierre du Calvet is one of the oldest houses in the city. Built during the French regime in 1725, the house has remarkable architecture and a fascinating history. From the outside, the Breton stone facade is built with 3-foot-thick field stone walls, iron window shutters, tall chimneys, French windows and a pitched roof. It is named after Pierre du Calvet, one of Montreal’s more colorful characters. A Hugenot merchant from France, he was appointed a Justice of the Peace following the British Conquest of 1760. Today, Maison Pierre du Calvet is an intimate 9-room boutique hotel known for hosting private receptions, business meetings, weddings, and romantic getaways. The house is also rumoured to be haunted. According to Haunted Canada 5, the ghost of Du Calvet’s wife, Marie-Louise Jusseaume, is known to interact with guests. While she is known to spook the female visitors, she is flirtatious with the men, often winking at them. With rooms renting for almost $400 per night, the Maison Pierre du Calvet offers an unforgettable experience for guests who want to soak up Montreal’s history – and possibly witness a ghost!

Donovan King is a historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbot College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec).

Comments (0)