McGill is a research-intensive university credited with many scientific discoveries and other inventions. However, there are certain research projects that went horribly wrong and the university tends to downplay them. One of the most devastating discoveries ever made occurred in McGill University’s MacDonald Physics Building, which is now said to be cursed.

Welcome to the one hundredth installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog! We are very proud of this important milestone!

With over 500 documented ghost stories, Montreal is easily the most haunted city in Canada, if not all of North America. Haunted Montreal dedicates itself to researching these paranormal tales, and the Haunted Montreal Blog unveils a newly researched Montreal ghost story on the 13th of every month!

This service is free and you can sign up to our mailing list (top, right-hand corner for desktops and at the bottom for mobile devices) if you wish to receive it every month on the 13th! The blog is published in both English and French!

Haunted Montreal is entering the holiday season! We have an online store for those interested in gift certificates and company merchandise. More details are below in our Company News section!

Our Haunted Pub Crawl is offered every Sunday at 3 pm in English. Tours in French happen on the last Sunday of every month at 4 pm.

Private tours for all of our experiences (including outdoor tours) can be booked at any time based on the availability of our actors. Clients can request any date, time, language and operating tour. These tours start at $215 for small groups of up to 7 people.

Email info@hauntedmontreal.com to book a private tour!

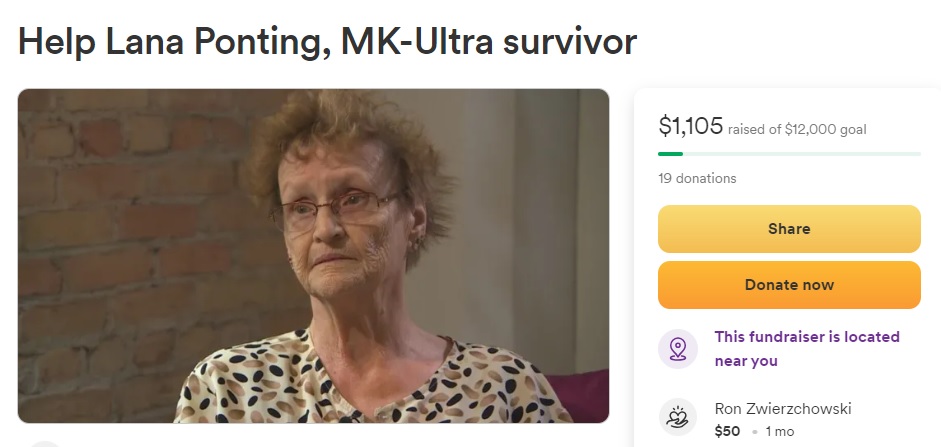

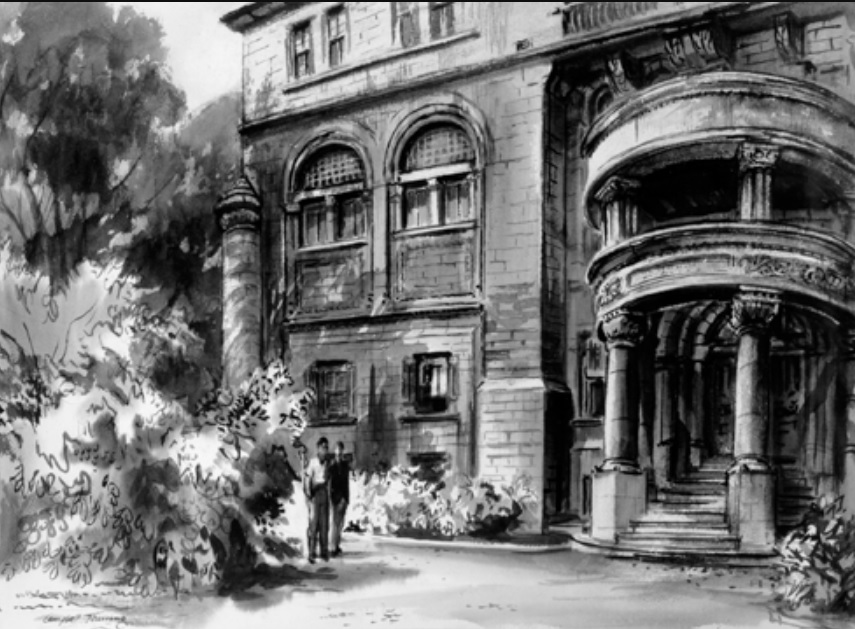

We are also supporting a fundraiser for a victim of one of Montreal’s most haunted and deranged buildings – the Allan Memorial Institute.

Details are in the Company News section below!

This month we examine, republish and translate into French “Nips Daimon”, a forgotten Victorian-era ghost story set in Montreal.

Haunted Research

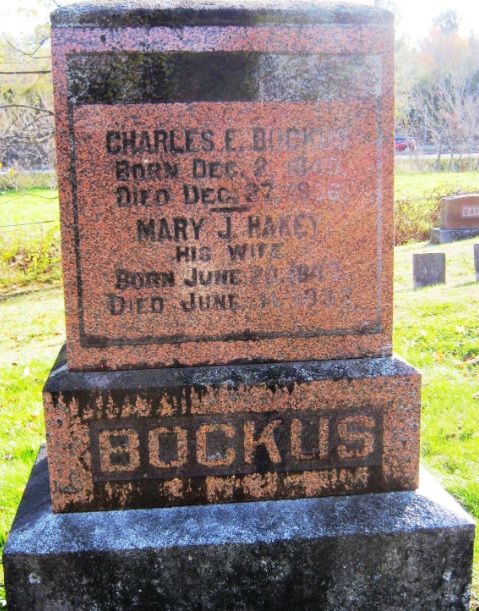

In 1862, author C.E. Bockus penned a ghost story set in Montreal called “Nips Daimon”. Published in London in the May edition of Once a Week, the creepy tale features a Mount Royal tobogganer named Eugene Roy and his misadventures with an undead spirit. Based on the true ghost story of Simon McTavish and his haunted castle, “Nips Daimon” adds another dimension to the deranged legacy of the forgotten fur baron.

Known to toboggan down the mountain slopes in his coffin at night, McTavish’s ghost allegedly terrorized city residents in the 1800s. The McTavish tale is widely considered “Canada’s Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and C.E. Bockus’ fictionalized version adds to its mystery and intrigue.

C.E. Bockus was a businessman, financier and journalist. Born in 1833 in Pictou, Nova Scotia, he went on to study at McGill University in Montreal. Undoubtedly, he learned the ghost story of Simon McTavish during his time on campus. Bockus died in Boston in 1901 at the age of 67. It would appear that “Nips Daimon” is the only work in his literary record.

Haunted Montreal is proud to present this amazing Victorian ghost story, which is largely forgotten in the city. We are also thrilled to announce that the talented Claude Chevalot has translated “Nips Daimon” into French for the first time ever.

Nips Daimon

by C.E. Bockus

ꙮ ꙮ ꙮ

Montreal is a wonderful place, unique in fact upon this continent, contrasting the ancient with the modern as no other American city can pretend to do, and showing buildings, dresses and habits, two centuries old, in picturesque juxtaposition with the extreme fashions and improvements of the present day. The grey and black robes of the nuns rub against hoops that are greatly beyond the gauge of the city sidewalks. Portly priests, or humbler frères chrétiens dispute the pavement with red-coated soldiers, and merchants whose credit is as solid as their granite stores. Convents jostle the counting-rooms of firms of world-wide reputation. A church, that counts its years by hundreds stands at the side of a market-house, much finer than any our city can show; while near them from the barracks issue in splendid array a little army of soldiers, whose march is like the moving of waters, and their drill a wonder and a school.

It is not astonishing, therefore, that every summer brings to Montreal a host of tourists to marvel and admire, in whose train follow the inevitable travelling correspondents, who fill the columns of our newspapers with their little collections of thrice-told facts. We “stay-at-homes” expect annually to be informed by the different journals that the towers of the French church are higher than the monument on Bunker Hill, and that the Enfans Trouvés of the Soeurs Grises have clean faces, but bad bumps. The nuns themselves, it seems, are not so pretty as they might be; while the smallest children in the streets talk French with fluency – a fact which I wish you to note as an evidence of their surprising precocity.

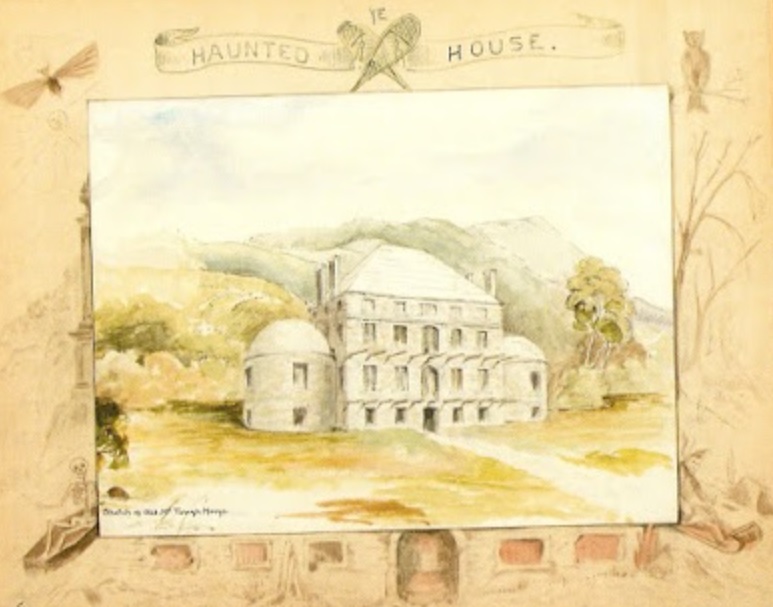

One special point no correspondent neglects. The Haunted House furnishes a paragraph to the whole tribe of nomadic scribblers.

Sometimes it is stated that the builder of this ghost-ridden mansion hung himself from a beam in its cellar, on discovering – what any sensible man would have expected – that his architect’s estimate covered less than half of the required outlay. Again, we are told that he died from the effect of a cup of “cold poison,” swallowed in humble imitation of the sad example of the illustrious Dinah. I remember one correspondent who struck out an original path, and declared that the devil carried him off bodily – though with what purpose or for what crime, this inventive writer unfortunately omitted to specify.

But, however they differ regarding the exit of the troubled spirit, all agree upon its occasional return.

Haunted the house is, – and deserted, – the very picture of desolation, standing alone, upon as fine a site as fancy can conceive, having behind it the broad green belt of lofty trees that garters the foot of the mountain, and in front a wide slope, which stretches its lawn-like expanse in regular descent from the great doorway of the mansion to within a short distance from the public street.

This hill affords summer-pasturage for hundreds of cows which lounge among the fruit trees at its base, or dot its surface with their forms. But in winter it is put to a livelier use, for which it is admirably fitted by its length, and height, and the evenness of the declination.

To wit – as a slide for tobogans.

“A what?” you ask; “in the name of euphony, what is a tobogan?”

Let me tell you. I must premise that the orthography of this word belongs to the important unsettled questions of the world. Authorities differ; usage affords no guide; and its etymology is lost in the dim ages of the aboriginal tradition. The way I write it comes as near the sound as can be, and pleases me accordingly. But any reader who feels dissatisfied has perfect liberty to spell it as he thinks proper.

All I know about toboganing was learned nine years ago. Understand that. Many changes may, nay must, have come since then. The hill may offer no longer an unbroken slope. The practice itself may have grown unfashionable. But in my time, everybody toboganed, and the slide was the glory of the town.

Tobogans – to resume them – are Indian sleighs, perfectly flat, without runners supporting themselves above the lightest snow, on the same principle as the snow-shoe, by offering a large surface to its resistance. They are about eight feet long, and sufficiently broad to leave a margin of a few inches on each side of the sitter. They curve upwards in front, like the runner of a sleigh. Light poles, tied along the sides, support the occupants while going over “the jumps,” which are holes worn by the constant ploughing of the curved fronts in their rapid rush down the steep incline.

Indian sleighs are often very neatly painted, and almost always christened by appropriate names, – such as the ‘Dart,’ the ‘Snow Wreath,’ and the ‘Bird on Wing.’ Their bottoms, by long use, grow wonderfully smooth. When the snow is a little beaten, or has a light crust, through which our New England sleds would crash in a moment, the tobogans glide along as easily as a ship passing through the water, and as swiftly as an arrow just loosened from the bow.

I spent a winter in Montreal, during the height of the furore, and visited the ground many times in company with as pleasant a set of gentlemen as I have ever been privileged to know.

One of these, whom I shall call Roy – Eugene Roy – for this most excellent reason, that it does not sound at all like the real name, was almost always the leader of our party to the hill. He was a young man, quite dark enough to justify the suspicion that he had Indian blood in his veins, – a strange, quiet fellow, who said very little to any one, who steered magnificently, and appeared to love sliding as he loved nothing else in the world.

No wonder. He owned the fastest sleigh on the field. It was a narrow tobogan, painted blue, carrying its name, the ‘Indian Chief,’ in wide gold letters upon the front. Its bottom was seamed with countless cracks, and worn so thin in many places as to be almost transparent. But it flashed down the hill as no other tobogan could be coaxed to do, darting out from a flight of its most formidable rivals, like a hawk sweeping past a cluster of slow-winged crows.

No hand save his own ever steered this sleigh, for, though Eugene was free as air with whatever else he possessed, he steadily refused to lend the ‘Chief,’ even for an occasional slide, to his most intimate friend.

He and I had some rooms in the same house, we always walked home from the hill together, and, indeed, soon became as intimate as his peculiar disposition allowed.

It is not surprising that the sliders, who spent so many evenings in the vicinity of the Haunted House came to feel, in time, a thorough contempt for its terrors, and passed, as regards the existence of its Ghost, in rapid progression from doubt to scepticism and positive unbelief. Many a shout from strong-lunged scoffers has rung through the rafters of that unfinished building, challenging all the spirits who dwelt therein to come forth and try their wings in a race along the hill. But I noticed that the boldness of the call invariably bore a nice proportion to the number of the party, and that, when no more than two or three sliders remained near the mansion, its reputed tenants were treated with the most respectful consideration by all. For there was something so utterly lonesome about this deserted dwelling, standing with blear boarded windows, white in the moonlight, the tomb of the pride of its builder, that its contemplation often chilled the boldest hearts and stayed the noisiest laughter.

We all spoke of it lightly, however, when distance had dissolved its spell; and at the suppers, which occasionally followed our return from toboganing, the spectral occupant of the desolate mansion was a frequent toast with the lads of the hill. One excepted, Eugene Roy, never emptied glass to that health, never smiled at the jokes, nor joined in the boasts that allusion to his ghostship had a tendency to call forth; nay, when pressed by our banter regarding his reserve, he always answered – that there were things he thought it ill to jest about, and that, perhaps, we would not find the devil so black as he had been painted; a supposition involving a corollary not very complimentary to the company.

One evening some person inquired of him if he “dare race his ‘Indian Chief’ with any other tobogan in Canada?”

We all felt interested on this point, as there had been talk of bringing up a famous sleigh from Quebec, and matching it against his for a medal. The supper drew towards its end when the question was asked. Roy had been drinking pretty freely. He looked up from his glass quite hastily, and replied with an oath that – “the winner of the race he had run one Saturday night need fear no wood that ever skimmed snow-drift.”

All at the table laughed. They had never before found Eugene influenced by his liquor. I reflected; and that evening on our homeward walk renewed the subject which we discussed rather warmly, till at last I taxed him with knowing more about the tenant of the “Haunted House,” than he appeared willing to admit.

On this he turned round upon me sharply.

“Do you believe in ghosts, in bodied or disembodied spirits?”

“Pooh!” I blew the answer out like a bullet, for I considered his question a reflection upon my good sense.

He stopped suddenly, and pointed towards the building, which from its commanding situation was visible at a great distance.

“So you have no faith in haunted houses?”

“Haunted they may be,” I laughed, “by rats, or owls, at the farthest by nothing more formidable than a skulking mountain fox.”

He caught my arm.

“Suppose I told you that I, myself, am the ghost, the devil, the thing whose accursed presence heightens the horror of those lonely walls?”

His voice and the light in his eyes were unnatural. Shaking myself from his grasp, I jumped into the middle of the road, but came back ashamed enough when I heard his mocking laugh.

“Again, as ever,” Eugene cried. “You are like the rest of mankind. Liars and cowards all of you – in matters supernatural,” he added calmly. “You scoff at ghosts. That goes without telling. ‘Brave comme un lapin,’ says the proverb, and you jumped from my side like a rabbit, because I spoke a few wild words in a deeper tone. Well, be not afraid. No matter what does haunt that old house; I don’t. Only take this advice from a friend. Till you get stronger nerves, never stay on the hill alone after midnight; and of all evenings of the week, choose Saturday least for solitary sliding!”

Of course, after such a speech, there were no means of resisting my eager curiosity. He told me his story that night, as we sat in my room together, while the flashes from the fire-light flickered about the chamber, till the shuddering darkness of the winter night overshadowed the room like a pall.

Impossible to give it in his words; needless my interrupting queries. You have it here, as I remember it, plus the many imperfections of a bad narrator, and minus more of the charms derived from his quaint expressions and peculiar manner, than I am at all willing you should realize.

“One Saturday night,” he commenced, “about four weeks ago, the tracks, you will perhaps remember, were in a terrible condition. There had been good sliding for a week, on snow deep enough even to cover the big rocks at the foot, and all the world had gone mad about tobogans. With Friday came a dash of rain, followed by severe weather, till on Saturday the whole hill was a sheet of glare ice, so thick that our sticks could not break through it, and so smooth that our hands found little hold to steer.

Few cared to go on it that afternoon. Those who did left early. For the sleighs shot down like arrows. To guide them was all but impossible. One boy went off with a broken arm; another, who had cut his ankle, was carried home on his tobogan.

It was towards ten o’clock in the evening when the moon got up, heartily cheered by half a dozen of us who were waiting, impatient at the hill. Little cared we for ice or danger; a moonlit slide at such a pace was cheaply bought by any risk. Good steerers all of us, you may be sure, and our tobogans the best of the town. George had the old ‘Hawk’s Eye’ cut down to half her original size, but with a bottom smoother than the ice itself. Mark brought a new sleigh which he had selected out of a hundred in Lorette. Frank, too, was with us; large-hearted Frank, whose name describes his nature, as good at cricket as at steering – deservedly a favourite with girls and men; and Andrew with the ‘Arrow,’ and Arthur’s ‘Falling Star.’

We had a glorious time. The speed was greater than I had ever before known. We did not slide; we flew, – dancing over “the jumps,” and flashing past the stone-heads, each steering as carefully as if there were a dozen ladies on board – for a mistake would have been no laughing matter. We tried all the runs, even the unusual one which, passing obliquely behind the college buildings, leads towards a bridge that crosses the little brook.

Near twelve o’clock, tired of our sport, and bed-weary, we ranged our sleighs at the door of the Haunted House for our last slide.

It was Frank who proposed that we should try the track on the extreme right, which as yet we had not attempted; and George who suggested that we should go far back among the trees, shoot through the fence which separates the inclosed ground from the rough foot of the mountain, and thus sweep along the right-hand track with all the advantage which our unusual start would give. By so doing we would nearly double the length of our slide. The track on this side was entirely free from obstruction till you approached the bottom of the hill, where the difficulties increased – rocks being in great plenty, and the trees inconveniently close together.

No one dissenting, we dragged our tobogans up the mountain, till we reached the ledge off which we purposed pushing; some of us, whose moccasins were travel-worn, finding it no easy task to scale the slippery ascent.

At the top, all tarried a moment, spell-bound by the beauty of the night. Not a cloud soiled the sky. No breath of air rustled through the leafless branches above us. The moonlight seemed unnaturally bright, even for that latitude, showing the towers of the French church on guard over the sleeping city below us, and beyond, blue in the distance, the crossed summit of Beloeil. Behind us rose the Monument, girt by a high wall of stone. We could see its shaft white among the tree-trunks, marking where rests the builder of the house in, as many believe, his troubled and terrible repose. But none of us thought of the monument or its tenant while we marshalled our tobogans along the edge of the incline – of nothing, in fact, but the track before us, and the wild scamper over it that we were about to take.

“Now then! The first to the bottom of the hill,” cried George.

“Give us to the fence, Roy, if you want an even race.”

“To the house you mean,” two or three called out; “at less than that for a start, ‘the Chief’ will be up with us before we reach the bend of the hill.”

“Hadn’t you better say half way down at once?” I answered. “You are a plucky set to have a race with. I would not take an inch from the devil himself.”

“Then stay, and try with him,” they shouted; and all, pushing off at once, dashed over the ice down the hill, darting in and out among the trees, shooting through the fence at different openings, and emerging in a body upon the clear field beyond. They were so well matched that it seemed as if a blanket would have covered them, and swept out of sight round the house in a moment, cheering and daring each other on like the fine brave fellows they were.

I sat quietly, a hand down on each side, ready to shove forward, waiting till they had reached the bottom of the hill. My patience was not tried; their halloo, coming through half a mile of that clear air as distinctly as if uttered ten yards off, told me that the track was clear for my run.

With this halloo came to my ears, from the steeples of the city, the sound of the bells ringing midnight; and I listened to distinguish the clear tones that bounded out of the belfry of Saint Patrick’s from the heavier clang of the Cathedral and the gentle music of the Seminary chimes.

Those twelve strokes, ringing above the sleep-bound city, were wonderfully subdued, and blended by the distance into so soft a peal, that I thought they sounded like the tongues of angels, proclaiming, with the advent of the Sabbath, a season or rest and tranquility to men. ‘Twas a devil’s blast succeeded them – a summons flung among the shuddering trees to chill my heart with horror.

“Arrête un peu, mon ami. Est-ce que c’est la mode maintenant de toboganer tout seul?”

The tone crisped my nerves like a musket-ball. I turned, and saw behind me a tall man, dressed in a blanket-coat, who carried snow-shoes at his back, and dragged behind him a tobogan unpainted, but so dark with age that it looked as if it had been varnished. His coat was buttoned to the throat, and tied about the waist with a silk sash, not red like mine, but of a peculiar shade resembling clotted blood. His leggings were ornamented along the seams by a fringe of long hair; a small fur-cap, adorned with the usual fox’s tail, partially covered the wealth of straight black locks that fell down towards his shoulders; while his feet, at which I glanced instinctively, were protected by moccasins, beautifully worked in beads, and coloured hair. No foot is handsome in a moccasin; his, as far as I could judge, seemed small for his size – voilà tout. His features, though marked, were far from disagreeable. He had the nose of an eagle, the eye of a falcon, a brown complexion, and a figure so slender as to be almost waspish. But long arms swung from his well-set shoulders, and it was plain that he possessed strength, combined with activity, in an uncommon degree. He moved, in fact, like a tiger, noiselessly, easily; in every motion the play of muscles seemed capable of sending him yards through the air at your throat any moment.

“It is the fashion now to leave a question unanswered?” he said with a sneering emphasis.

The smile, more than his words, recalled me to myself; for pride came to the rescue of my courage – the shame of cowering thus before a stranger, odd, but not bad-looking, at all events decidedly gentlemanlike in carriage and address, who had spoken to me twice civilly enough, and remained now waiting for my replies with politeness which must be changing very rapidly into contempt.

“I beg your pardon,” I said; “I was greatly surprised by seeing any person on the mountain at so late an hour.”

“Not half so much as I,” he cried, “It is generally lonely enough up here long before midnight.”

“Do you come, then, often after twelve o’clock?” I inquired, astonished.

“Often,” he answered. “Does not my sleigh look as if it had been used? This is the best time for a slide. The tracks are not covered with shouting fools, who could hardly steer clear of a haystack, if one stood in the middle of the hill.”

He glanced at my ‘Indian Chief’ – the glance of a connoisseur, appreciating all its merits, and discovering every defect.

“That is a pretty piece of wood you have there. Hardly heavy enough in front, and too wide for a night like this, though I dare say it does very well on a light snow.”

“You may say so,” I interrupted, with some warmth. “Drift or ice-flake matters little, for on neither have I found its equal.”

He drew his sleigh toward him, and placed it alongside of mine, which looked three inches broader.

“My own is narrow” – he continued, speaking no longer in a defiantly-sarcastic tone, but low and very sadly, till his voice thrilled through me like the wail of a winter wind –”too narrow, indeed. It hurts me, and I am weary of it. I would gladly change it for your painted ‘Indian Chief.’ Ah me! I have seen many chiefs, painted after a different fashion. The smoke of their wigwams is with yesterday’s clouds, and the track of their tobogans on last year’s snow. Come,” he added, more cheerfully, “I will make a bargain with you. Have you heart enough to race me one slide along the hill?”

“Why not?” I answered. “I will beat you if I can with all the pleasure in the world.”

I felt so ashamed of my late cowardice that, if he had asked me to follow him over the mountain, I believe I would not have refused; and, besides, il faut quelque fois payer d’audace.

“Then let us start,” he said. “If you are the victor, you may keep your tobogan as long as wood and deerskin hold together. But if I conquer, I warn you that I shall want your sleigh and that you must use mine.”

“A moment,” I answered. “This is a strange bargain – ‘tis heads I win, tails you lose. I am to keep the swiftest in any event – mine, if it best yours, yours if better than my own.”

“You agree then?”

“I should be a fool to refuse.”

“That is not my affair. Eh bien, c’est connu. Touch there, my friend.”

He stretched out his hand, which I touched at first as you would handle hot coals, but more heartily when I saw the sneer starting over his face once. How brave we are – afraid even of being afraid.

The stranger slipped his snow-shoes from his back, and flung them against a tree, remarking that he would pick them up on his return.

“Are you coming up the hill again to-night?” I inquired with surprise.

“It is not night now, but morning,” he answered; “the morning of the Sabbath.”

“And will you slide on Sunday?” I asked.

“You should have remembered that ten minutes ago,” he replied, in his old sarcastic tone. “Think no more of it. Think of nothing but the stakes in the race before us. All other considerations are now too late.”

We got off together, but parted company from the very outset, for he shoved to the left at once and steered toward a gap in the fence directly behind where a break in the wall of the Haunted House gave access to the cellars beneath – an old doorway, in fact, which pilferers had plundered of its boarding, and the mountain winds of its stones, till an irregular opening had been formed large enough to admit a loaded waggon.

At first, as the stranger headed in the direction of this door, I thought that he had mistaken his course, or that his tobogan had become unmanageable. But the skill with which he handled it dismissed this last supposition. His sleigh bounded from knoll to knoll, obeying a touch of his finger, scraping the trees as it flew past them, and taking advantage of every bend in the ground, till it sprang straight at a hole in the fence not much wider than itself, and shot through, as the thread goes through the needle when guided by a woman’s hand. I never saw such steering before or since. After what followed, you may believe that I hope never to look upon its like again.

I had got abreast of the fence myself by this time, running down it towards an opening farther to the right. The pace was awful. My tobogan sheered along the ice so that I could hardly keep it upon the track, and I came within an inch of missing the gap altogether. When I reached the other side, the stranger was just flashing into the gloom of the opening that led downwards to the cellars of the Haunted House.

I screamed. But my voice was drowned in a peal of infernal laughter, and the clapping of countless hands, which rattled from every story of that fiend-ridden building.

Straight in front of me I stared – not a side-look for a million. On my head each separate hair crawled upward, snake-like, and my breath went and came pantingly, as that of a man who struggles body to body with a mortal foe. My tobogan bounded on with redoubled speed. It seemed to share my terror.

‘Twas not without an effort that, as I passed the end of the mansion, I mustered courage for a Parthian glance.

What I saw will live before my eyes till they close on this earth and its terrors for ever; a vision of horror ineffable – beyond belief or bearing – compared with which all I had before imagined of ghastly, soul-subduing phantoms, became mere babble of old nurses to frighten timid children.

Out of the darkness into which my companion had plunged came forth a skeleton bearing in its skinless arms a coffin of unusual size. Its knees rattled as it strode forward staggering under the terrible burden. Nothing of life about it save its eyes; not earthly, even these. From the browless holes beneath its bony forehead looked out two balls of fire, the same that had glared on me a moment before, as I was looking up in the stranger’s face. To look at them now threatened madness. I felt it, and shut my own, pressing my hands over them to keep out the hateful sight.

So I saw nothing more. But I heard the thud of the coffin upon the ice, and the clatter of the skeleton’s bones, as it bounded into its sepulchral vehicle; then the grit of the frozen snow beneath the rush of that devil’s tobogan!

This last sound chased irresolution. I knew what a struggle lay before me. With strength gained from despair I nerved myself to meet the danger, feeling that human skill and courage must be strained to distance my demon pursuer.

If I failed, what then? I shuddered to think of it. New light had been flung upon the strange conditions of our race, and well I understood their meaning. No marvel that he found his tobogan too narrow. No wonder that he wearied of it and would change it for my ‘Indian Chief’. In the coffin, which thundered behind me, I was to make the next skeleton. Had he not said that I must use it, unless I conquered in this hopeless race?

Thus, life and death on its issue, I bent myself to the contest, losing not an inch that all I knew of steering and the hill could give me.

I have said before that the right-hand track was singularly free from obstructions till you approach the foot of the hill. The descent was much more even than on either of the other slides, so that, at first, dexterity and practice availed but little, the utmost any one could do being to keep the sleigh headed straight toward a stump near the bottom, round which the track bent at an angle unpleasantly acute. On a line with this stump — not quite two yards to the right of it — the sharp black top of a rock peeped out above the ice-crust.

The passage between this Scylla and Charybdis was not easy to hit on such a night, when a wrong touch of the finger would have sent the sleigh twenty yards from its course. But a greater danger lay beyond. Three or four yards further on, facing the centre of the passage, the trunk of a large tree, with wide-spread roots, completely barred the way in front, leaving only a narrow gap upon the left, into which the steerer had to turn so sharply and suddenly, that, even at ordinary speed, this bend was considered the most difficult piece of sliding on the hill. Of course the difficulty, as well as the danger, increased proportionally with the pace. That night both reached their maximum. A tobogan striking against any obstacle with the frightful impetus with which mine was bowling down the ice, would be knocked to pieces in a moment, and its rider be very fortunate if he escaped with a broken limb.

But I thought little of the perils before me. It was the danger behind that engrossed my attention.

I stretched myself at full length upon the ‘Chief,’ bringing my weight to bear along its centre as evenly as possible; for the Indian sleigh never gives its best speed to the rider who sits up-right. Thus, on my back, looking towards the stars, and listening to the grating of the ice-crust under the heavy coffin that followed me, I passed a moment of as intense agony as, I think, ever fell to the lot of mortal. Cold as was the night, the perspiration rolled in clammy drops down my forehead, while my teeth closed so firmly together that they ached under the pressure.

Judging as well as I could by hearing alone, I concluded that my pursuer followed not directly in my rear, but a little on the left of my course. An instant afterwards the noise grew more distinct, and my heart sank; for I felt that he was gaining on me. Then the noise changed to my right, from which I presumed that he had crossed behind me and taken an inside position, partly because the ground, being there somewhat steeper, favoured the weight of his ponderous conveyance, and partly because – if he could get alongside of my sleigh in this position – it would be easy for him to force me out of the path against the stump that guarded the left of the narrow strait toward which both were rushing.

Having now the advantage of the ground, and even, as was evident, the heels of me in an equal race, he overhauled me very rapidly.

Nearer and nearer came the sweep of his infernal tobogan. It followed – it approached – it closed upon me. I glanced a-head – the trees were yet a hundred yards away – then around. The front of the coffin was level with the end of my tobogan.

Another second. It was up with my shoulder, looking ever so black and hideous against the purity of the frozen snow.

In that breath a thought came to me; not so much a thought as an inspiration.

I carried on my watch-chain a small gold crucifix, a present from my mother the night before she died. I remembered well, at that moment, what in my heedlessness I had long forgotten that this crucifix, which had remained in our family many years, was valued as possessing more than ordinary sanctity. It was of admirable workmanship. It had been blessed by a bishop, and, report said, worn once by the Superior of a convent, a lady of singular piety, whom, after death, for her good works the church had canonised. My mother, when confiding it to my care, made me promise that I would carry it constantly about my person – a promise kept neglectfully enough by attaching it as a charm to my chain.

One vigorous pull tore open my coat, another broke the clasp which secured the crucifix. I held it high above my head, neither expecting or daring to hope for help, but clinging to the cross with the same strong, despairing grasp which drowning men fasten upon a straw.

With that, close to my right hand, I heard a clatter, as of boards falling in on one another, while a yell of rage disappointed, and terror indescribable, swept in the direction of the “Haunted House,” where it was taken up by an infernal chorus which seemed to send its echoes into the very heart of the mountain.

Then my sleigh rubbed with a sudden shock against some obstacle, and, overturning at once, hurled me many yards along the ice-crust, spun helplessly into insensibility.

When perception returned, I found myself surrounded by friends, who, in their anxious care, had placed me upon my tobogan, and were occupied in forcing some very good brandy down a throat not usually so reluctant to receive it.

My face was bleeding from a cut or two. One of my hands had been badly bruised in my scramble over the snow. These, physically, were all the injuries I sustained from my race with the devil down that terrible hill. Mentally, however, mischief had been done not so easy to cure.

To this hour Saturday midnight finds a nervous coward, terrified by every noise, alarmed by every shadow, imagining through each open doorway the approach of a flame-eyed skeleton, and hearing in each creak upon the stair-case the foot-fall of the lonely slider who stables his tobogan in the cellars of the “Haunted House –”

Hic finit Eugene’s story, told toward its end to a listener who was buried under blankets.

“Very well;” you ask. “Now, is this true or false?”

One test of its truth I might readily have applied. Nothing easier than to go upon the hill on Saturday evening, and stay there alone till twelve o’clock.

This idea did not occur to me that night. But the thought and purpose to execute it forthwith came next morning. Unfortunately it happened, throughout the rest of the season, that I had some pressing engagement every Saturday evening, which either prevented me from going on the hill at all, or brought me off it, with the crowd, long before midnight.

But be comforted. It is not unlikely that the hill and the house remain still intact. Should you happen to be in Montreal next winter, try the experiment for yourself. I can promise you a magnificent slide. If the spectre catches you, tant pis pour vous.

– C. E. Bockus

ꙮ ꙮ ꙮ

Source: C.E. Bockus, “Nips Daimon”, Once a Week, (24 May 1862): 602 – 08

Company News

Haunted Montreal is entering the holiday season!

Our Haunted Pub Crawl is offered every Sunday at 3 pm in English. Tours in French happen on the last Sunday of every month at 4 pm.

Private tours for any of our experiences (including outdoor tours) can be booked at any time based on the availability of our actors. Clients can request any date, time, language and operating tour. These tours are based on the availability of our actors and start at $215 for small groups of up to 7 people.

Email info@hauntedmontreal.com to book a private tour!

You can also bring the Haunted Montreal experience to your office party, house, school or event by booking one of our Travelling Ghost Storytellers today. Hear some of the spookiest tales from our tours and our blog told by a professional actor and storyteller. You provide the venue, we provide the stories and storyteller.

We are also offering Christmas Ghost Stories: A Quebecois Tradition, which we have previously offered as a virtual tour, as an in-person Travelling Ghost Storyteller experience.

To find out more, please contact info@hauntedmontreal.com

Our team also releases videos every second Saturday, in both languages, of ghost stories from the Haunted Montreal Blog. Hosted by Holly Rhiannon (in English) and Dr. Mab (in French), this initiative is sure to please ghost story fans!

Please like, subscribe and hit the bell!

In other news, if you want to send someone a haunted experience as a holiday gift, you certainly can!

We are offering Haunted Montreal Gift Certificates through our website and redeemable via Eventbrite for any of our in-person or virtual events (no expiration date).

We also have an online store for those interested in Haunted Montreal merchandise for the holidays. We are selling t-shirts, magnets, sweatshirts (for those haunted fall and winter nights) and mugs with both the Haunted Montreal logo and our tour imagery.

Purchases can be ordered through our online store.

Lastly, Haunted Montreal is soliciting donations on behalf of Lana Ponting, one of the last survivors of the CIA-funded brainwashing experiments at McGill University’s Allan Memorial Institute. At 82, Lana is living with food insecurity in Winnipeg. Like other survivors and their families, Lana hopes that a class action lawsuit will eventually bear fruit.

Please consider making a donation, no matter how small, to the GoFundMe Page that was set up for Lana’s well-being.

Haunted Montreal would like to thank all of our clients who attended a ghost walk, haunted pub crawl, paranormal investigation or virtual event!

If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page and/or Google Reviews, something that really helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours. We are a small, specialized tourism company for fans of deranged history, ghost stories and the macabre and appreciate all the support and feedback we can get!

Lastly, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list.

Coming up on January 13: Sûreté du Québec Police Headquarters

Located on the site of the former Fullum Street Women’s Prison, the Sûreté du Québec Police Headquarters is rumored to host all sorts of paranormal activity. Disembodied screams echo throughout the building, officers have spotted a ghostly inmate wearing a straitjacket, and sometimes the nauseous stench of burnt food – wafting from an unknown source – disgusts staff on duty. To further the headaches of the commanders, a major cockroach problem has made working conditions even more uncomfortable for Quebec’s largest police force.

Author:

Donovan King is a postcolonial historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbott College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec). He is also a certified Montreal Destination Specialist.

Translator (into French):

Claude Chevalot holds a master’s degree in applied linguistics from McGill University. She is a writer, editor and translator. For more than 15 years, she has devoted herself almost exclusively to literary translation and to the translation of texts on current and contemporary art.

Congrats on all the BRILLIANT GHOSTS to the 100th.

A pure pleasure in reading monthly. I look very forward to thr 13th with awe. Many thanks