This month we provide an update on the Hôpital de la Miséricorde and analyze controversial plans by Hydro-Québec to integrate an electricity substation into the haunted site. The ghost-ridden Hôpital de la Miséricorde has been empty for years and is starting to crumble. Located on prime real estate in Downtown Montreal...

Welcome to the forty-seventh installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog!

With over 300 documented ghost stories, Montreal is easily the most haunted city in Canada, if not all of North America. Haunted Montreal is dedicated to researching these paranormal tales, and the Haunted Montreal Blog unveils a newly-researched Montreal ghost story on the 13th of every month! This service is free and you can sign up to our mailing list (top, right-hand corner) if you wish to receive it every month on the 13th!

We are also pleased to announce that all of our ghost tours are now operating and tickets are on sale! These include Haunted Mountain, Haunted Griffintown, Haunted Downtown and the new Haunted Pub Crawl!

Our July blog examines the Haunted Statue of Jacques Cartier in Saint-Henri, a colonial relic of the past that is said to sometimes disturb people with its paranormal antics.

HAUNTED RESEARCH

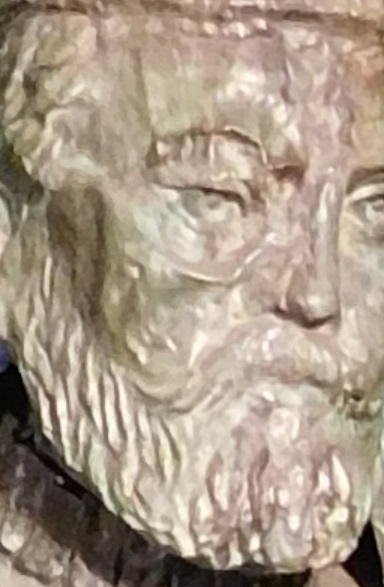

Towering over Saint-Henri Park is a statue of Jacques Cartier perched atop a fountain that is rumoured to be haunted. Striking a victorious pose over a fountain adorned with four decapitated Indigenous heads, the monument has been described by community activists as colonial and racist. While some local citizens want the statue removed because it celebrates genocide, others want it gone because it is allegedly haunted. Reports exists of the statue’s eyes following people. Others have heard it cackling maniacally at night and a group of tourists was shocked when the beheaded Indigenous decorations began spewing out what appeared to be blood.

In Montreal, statues are the responsibility of the Public Art Bureau. Established in 1989, the tax-payer funded organization is responsible for managing the municipal collection of public art and this includes acquisitions, maintenance, restoration and promotion. Today, the collection includes more than 320 artworks integrated into public spaces and municipal buildings, such as statues, monuments, murals, fountains and sculptures.

Concerning the statue of Jacques Cartier in Saint-Henri Park, the Public Art Bureau’s website describes it in a way that seems uncritical and casually racist:

“The focal point of Parc Saint-Henri, the monument-fountain is situated in the centre of a pool and stands on an octagonal base decorated with bulrushes. On the base sit four large basins alternating with four small columns topped with cups with fountain jets. In the centre, four beavers hug the base of the pedestal. The top part of the monument has three sections. The bottom one is adorned with foliage branches knotted together with a ribbon and heads of Aboriginals. The middle one bears inscriptions relating episodes in Cartier’s career. The top one is pierced with an opening for the mouth of a large fountain jet. On top of the monument is the sculpture of Cartier, portrayed as a valiant explorer, wearing a cap and the cape and baggy knickers that were in style during the reign of Francis I. His right hand rests on his sword belt and his raised left arm points west. At his feet is a tree stump, the symbol of a country to be cleared.“

Saint-Henri Park was originally called Jacques Cartier Square when it was created in 1890. Town of Saint-Henri mayor, Eugène Guay, purchased the land to create a public square for the enjoyment of the sector’s business elite. Inspired by 16th-century Italian gardens, the original square was landscaped with grass and trees and fitted with a dozen benches to promote relaxation.

For a focal point, the mayor took up a collection to hire Joseph-Arthur Vincent to create a Second Empire-style cast iron fountain surmounted by a statue of Jacques Cartier. Vincent carved the statue out of wood and surrounded it with copper plating, a less expensive way to create impressive-looking monuments. The work was intended to celebrate French-Canadian history by demonstrating the dominance of explorer and colonizer Jacques Cartier. When it was first unveiled in 1893, ten thousand residents attended the ceremony, attesting to the popularity of the “Monument to Jacques Cartier” at the time.

At the turn of the 20th century, upper middle-class homes were built around the square in stone, including one for Mayor Guay himself.

When the Georges Etienne Cartier Park was created in 1910, Jacques Cartier Square was renamed Saint Henri Park to avoid confusion.

In 1957, the City of Montreal announced its intention to move the statue to Mount Royal, prompting a citizen backlash.

While the locals managed to save the monument, in the 1960s, the upper middle class citizens gradually began moving away from the area.

Time was taking its toll on the park. By 1963, water had infiltrated the interior of the fragile monument and it began to crumble. In 1979, it was replaced by a copy made of epoxy resin.

In 1990, local residents founded Comité Statue-ta-Fête, a committee to enhance and improve the monument. The original statue was restored and placed in Saint Henri metro station in 2001, whereas a new version, cast in bronze, was prepared to stand atop the fountain in the park.

In 2012, the new statue was unveiled in the park by the Public Art Bureau for 477th anniversary of Jacque Cartier’s visit to the island at a cost of $83,000. Comité Statue-ta-Fête was awarded an Orange Prize in heritage preservation for its lobbying.

Some Montrealers were surprised that so much money and effort went into restoring a statue that celebrates colonialism, domination and even genocide, whereas others whispered that the City should have removed it for good due to persistent rumours that it was haunted.

While rare, haunted statues are known to exist and disturb people throughout the world, as described on the Youtube video “10 HAUNTED STATUES Caught On Tape“. Like the others, Montreal’s statue of Jacques Cartier is also known to upset people through its paranormal antics.

In the 1970s, Marie-Josée (not her real name as she prefers to remain anonymous) was a single mother. She met a local man who had a steady job and soon married him to provide her daughter with a more stable upbringing. After the wedding, the family moved into one of the stately homes bordering Saint-Henri Park on Rue Agnès. She reported that after she had moved in with her husband and young daughter, she began experiencing problems with the statue of Jacques Cartier in Saint-Henri Park.

The first night in their new home was like a dream come true. Marie-Josée and her new husband were thrilled to be in such a beautiful old house overlooking a Victorian park, with plenty of space to raise her daughter.

That first night the family ordered in Chinese take-out as they began the arduous task of unpacking all of their belongings from numerous boxes scattered throughout the house.

At around 9 pm, Marie-Josée was putting her daughter to bed when she heard what sounded like laughter coming from outside. She opened the window to see if there were rowdy teenagers in the neighborhood, but could not see anyone on the street or in the park across the street. While she could not place the laughter, she recognized the voice as male. The laughter got louder, and soon transformed into a mixture of snickering, giggling and cackling. Unimpressed, Marie-Josée closed the window and secured its latch. Unfortunately, she could still hear the deranged laughter, albeit more muffled.

“Maman, why is someone laughing outside?” asked Marie-Josée’s daughter, stating “I’m scared”.

Marie-Josée had to sleep with her daughter that night, and the evil laughter continued on an off throughout the night.

The next morning she went outside and crossed the street into Saint Henri Square to see if she could find any clues as to what had happened the previous night. She saw people feeding pigeons from benches and squirrels darting through the trees. In the center of the park she noticed a big fountain with water pouring down. On the top of it was a triumphant man with a sword standing on a tree stump.

She read the writing on the base and soon realized that this was none other than Jacques Cartier, a man she had learned about in high school when studying History. She recalled that in the 1500s he had discovered Canada and claimed the land for the King of France.

She looked up at the statue and was studying it when something caught her eye. It was the eyes of the statue. It appeared as though they were staring directly at her. She began moving, keeping her gaze locked, and began to feel troubled when it appeared as though his eyes were following hers. It was almost as though he was giving her a cork-eye or a dirty look.

Marie-Josée was even more shocked when it appeared that the statue was smirking at her. Was she imagining all of this? She slowly backed away, but was pretty certain the statue’s eyes were following her. She broke eye-contact with the ominous statue and turned around to return home. That’s when she heard the snickering sound again, which seemed to be coming from the statue itself.

That evening, when her husband came home from work, Marie-Josée informed him about the disturbing, seemingly paranormal statue and its irritating antics.

“So what?”, asked the husband, explaining “He’s the founder of Canada and has every right to do what he wants.”

“Yes,” said Marie-Josée, “But he’s a statue.”

Her husband shrugged, let out a sigh and asked her to bring him a cold beer, before turning on the television to watch sports.

Over the next several days, Marie-Josée and her daughter continued to be unnerved by the malicious cackling and laughter seemingly coming from the haunted statue. It was becoming more and more unbearable.

Marie-Josée invited a friend over, who was a medium, and told her about her problems with the statue. The medium investigated and informed her that the statue was indeed haunted. She explained that the colonial explorer did a lot of bad things and was essentially a very arrogant man. The laughter coming from the statue was a reflection of his misdeeds.

Marie-Josée informed her husband of the news and again he shrugged and turned on the television. Marie-Josée was becoming more and exasperated and told her husband that she and her daughter could not continue to live under such unbearable conditions. She wanted to move somewhere else.

“But chérie,” said the husband, “We just moved in to this wonderful house! We signed a lease for a year. Now let me watch my sports in peace.”

“Yes,” said Marie-Josée, “But that cursed statue is driving us crazy! We want to live somewhere else where it is more peaceful.”

A heated argument evolved and before long there was screaming and shouting echoing throughout the house. Marie-Josée’s daughter started bawling.

Realizing that she was in an impossible situation and angry with her new, insensitive husband, Marie-Josée decided to leave him that very night, with her weeping daughter in tow.

Even though they tried to patch things up over the next several months, the relationship ultimately ended in divorce.

More recently, in 2014, a group of Korean tourists was visiting Montreal, and Saint-Henri Park was on their tour bus agenda because of its colonial statue.

The guide, licensed by the City of Montreal and a member of the tour guiding monopoly, wanted to teach the tourists about Jacques Cartier, the “Father of Modern Canada”. He had been taught about the importance of Jacques Cartier in his high school History course and at the mandatory tour guiding program at the ITHQ, which markets itself as Canada’s best tourism school.

When they arrived in the square, the guide proudly pointed out the sculpture-fountain and all its distinct features. He gushed as he pointed out that Jacques Cartier had claimed all this land for the King of France, and that the statue symbolized European domination over the aboriginals, animals and plants in the New World. The guide was about to explain how Jacques Cartier’s discovery led to a modern Canada, when suddenly one of the female Korean tourists pointed at the statue, shrieked and then fainted on the spot!

The guide rushed to her assistance, and began splashing water from the fountain on her face to try and revive her. When she came to, she began screaming in Korean, before picking herself up and running off.

The guide was shocked and he asked the Korean tourists what the problem was.

“She saw blood,” said one of the tourists, “Coming out from the mouths of the decapitated aboriginal heads.”

The guide scoffed at the time, but has been haunted by the experience ever since. When he is drunk, sometimes he tells the story, still in utter disbelief.

One burning question about racist statues is what to do with them in the 21st Century Age of Truth and Reconciliation. Recognizing that Montreal has some of the most racist statues and commemorations in Canada, Nakuset, executive director of the Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal is critical of the colonial monuments, stating: “I don’t think in any other culture you can kill, you can do a genocide and then celebrate it…It’s very disturbing.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued a report with 94 Calls to Action, and Call to Action 79 ii deals with heritage and commemoration:

“We call upon the federal government, in collaboration with Survivors, Aboriginal organizations, and the arts community, to develop a reconciliation framework for Canadian heritage and commemoration. This would include, but not be limited to:

Revising the policies, criteria, and practices of the National Program of Historical Commemoration to integrate Indigenous history, heritage values, and memory practices into Canada’s national heritage and history.”

The problem is that the wheels of change are very slow, and Montreal’s citizens are becoming impatient with all the racist monuments littering the city and driving away progressive tourists.

Racist statues, such as Sir John A. MacDonald and Queen Victoria, have been repeatedly painted by anti-colonial activists, who are demanding that they be retired to a museum or archive as “relics of the past”. However, instead of removing the racist monuments, the Public Art Bureau spends thousands of dollars each time re-editing them back to their racist versions by removing the paint and re-waxing them.

Montrealers are beginning to question this waste of taxpayer dollars and ask why the City isn’t doing anything about the postcolonial scandal.

Anishinaabeg visual artist Scott Benesiinaabandan believes: “If a group of Indigenous Canadians decided to go and protest in front of statues, then they would become controversial and people would start talking about it. But for the moment, nothing is happening.”

Perhaps the City of Montreal simply doesn’t know what to do with so many racist statues, plaques and monuments scattered all over the metropolis.

It would be wise for municipal authorities to study progressive artistic solutions that have been tried in other lands that are also in the process of decolonizing. This artistic idea of Reflectionism is appealing: it seems both creative and reasonable. Cities such as Asunción, Hamburg, Budapest and Odessa have all invited artists to rework and recontextualise statues with troubling legacies, with interesting and even powerful results.

Solution 1: Leave the paint on them

This is certainly the easiest solution in the short term, as it requires no expense and causes onlookers to question why the statue has been “vandalized”. This creates a fun sort of game where people will Google what is so bad about the statue, improving education and critical thinking in the general population.

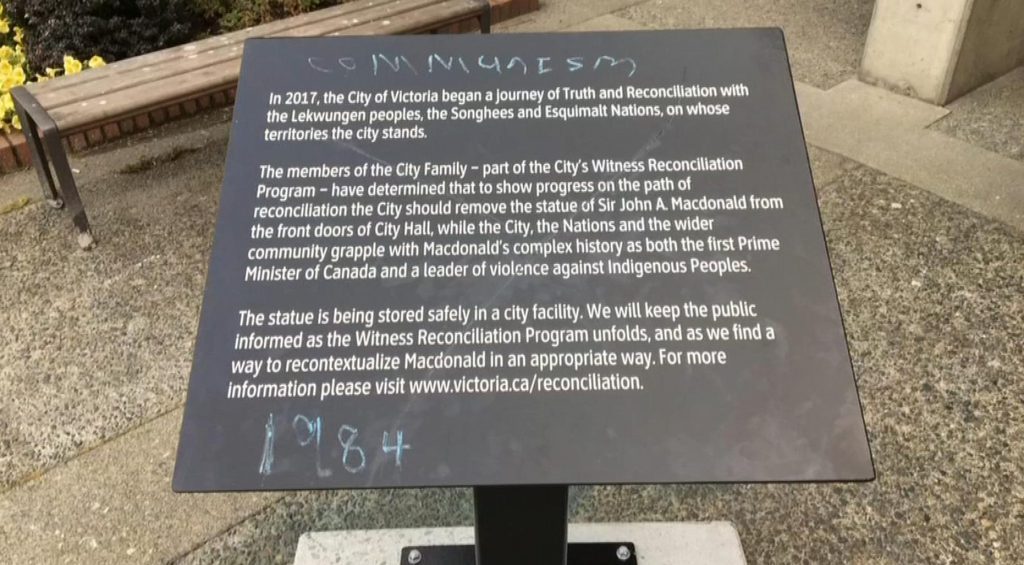

Solution 2: Interpretive Panels

Another solution, albeit not a very strong one, is to surround each racist statue or monument with interpretive panels explaining why it is racist and why it is still on display in a City of Reconciliation. The only problem with this approach is that there is no guarantee it will stop activists from painting the statues – and maybe even the panels!

Solution 3: Put them in a museum or archive

In order to preserve and reinterpret racist statues and monuments, museums and archives are ideal places for them. Not only are they protected from paint editing, but they can be put behind glass or stored as colonial relics of the past. This is the preferred solution for a group called the “Delhi-Dublin Anti-Colonial Solidarity Brigade”, who have claimed responsibility for editing racist statues with paint on many occasions, such as before the Mass Demonstration Against Racism and Xenophobia on March 24, 2019. Furthermore, museums can also digitally preserve the racist statues in their present locations with the use of virtual reality. That way, die-hards and anti-racism researchers can still experience the racist statues in their original locations, albeit via a VR interface.

Solution 4: Create an open-air museum by putting them all in one park

Memento Park displays more than 40 Communist-era statues in Budapest, Hungary. With the fall of Communism in 1989, Budapest was left with many undesirable public works of art that celebrated the oppressive era. Four years later, the city government decided to save the statues and the idea for the Memento Park was born. Today, the park is visited by 40,000 people annually, making it a popular tourist attraction for the city.

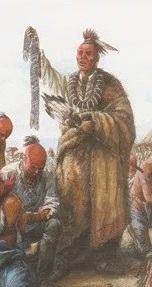

Solution 5: Responding by installing an In situ anti-racist statue or work of public art

It is possible to subvert a racist statue by placing another statue or work of public art in the same vicinity to trigger reflection on it. For example, in 1701 an exceptional Indigenous diplomat named Kondiaronk was able to persuade old enemies to sign The Great Peace of Montreal, effectively ending warfare in the region. Kondiaronk died during these negotiations, and was buried under Place d’Armes. Sadly, the genocidal Maisonneuve Monument was erected in 1895 in the center of the square with no dedication to Kondiaronk. To correct the problem, the City could erect a giant statue of peace-maker Kondiaronk, In situ, that towers over the racist Maisonneuve Monument in Place d’Armes.

It would signify that peace and inclusion is more important in Montreal than racism and genocide, and would restore Kondiaronk to his rightful place in the city’s history.

Solution 6: Physically alter the statue to subvert its original meaning.

Modern technology makes it easy to edit old statues by adding new elements that subvert their authority. For example, there are creatures from Kanien’kehá:ka and Haudenosaunee lore known as Kanontsistonties, or Flying Heads. These horrifying undead creatures are described as giant, disembodied heads the size of a human with bat-like wings, and a mouth packed full of fangs. Flying Heads were renowned to have an insatiable hunger for flesh and blood, which could never be satisfied because the creatures have no body. By adding hungry Kanontsistonties to racist statues, whereby the Flying Heads are presented as devouring the colonial figureheads such as Sir John A. MacDonald, Sieur de Maisonneuve, James McGill, Queen Victoria and Jacques Cartier, a playful new interpretation would be possible for delighted tourists.

Indeed, a whole tourist circuit could be created to visit all of the hungry Kanontsistonties additions to racist statues.

Solution 7: Deconstruct them

Deconstruction involves breaking the statues apart in order to rebuild them in ways that subvert their authority. Following dictator General Alfredo Stroessner’s ouster from power in 1989, Paraguayans found themselves debating the fate of his massive steel likeness situated at the highest point of Asunción, the capital of Paraguay.

Some wanted it removed, while others argued for its place in history. In 1991, the racist statue of the former Paraguayan dictator was shattered, prompting artist Carlos Colombino to reconstruct some of its remains within two slabs of concrete.

Solution 8: Sink them into the river to create a scuba park

Underwater statue parks are becoming more and more common as scuba divers demand increasingly interesting destinations. Given that Montreal is an island and therefore surrounded by water, this is an interesting option, especially given the lack of underwater attractions.

Solution 9: Beheading

Off with their heads! Postcolonial activist Andre Blaise Essama likes to behead colonial statues in Douala, the economic capital of Cameroon. A hero to many, but a notorious criminal to the local government, his goal is to replace all the colonial statues in the city with those of national heroes who fought for the bilingual country’s independence. He gained national attention in 2015 after he beheaded the statue of a French colonial hero named General Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque.

With so many options, the City would be wise to do a Public Consultation with all stakeholders, including in affected Indigenous communities, to determine the fate of the racist public art currently polluting Montreal.

Being a true City of Reconciliation takes a lot of courage, dialogue and progressive action. Whichever postcolonial solution the City of Montreal ultimately chooses, if any, will be a direct reflection on how serious Quebec’s only metropolis is about its commitment to Truth and Reconciliation.

Recent Media on the topic:

CJAD Radio 800 with Anne Lagacé Dowson. Interview with Donovan King about Haunted Montreal and Griffin Tours. July 9, 2019.

APTN National News. Local guide calls for revisions to Montreal’s colonialist monuments. Lindsay Richardson. July 3, 2019.

COMPANY NEWS

Firstly, a special announcement. We will be launching Griffin Tours in early August as an umbrella company for Haunted Montreal, Irish Montreal Excursions and our new Hidden Histories of Montreal walking tour. Griffin Tours aims to bring new, 21st Century experiences to next-generation visitors and tourists. Details coming soon!

Secondly, we are in the planning stages for a Ghost Hunt in the old Sainte Antoine Cemetery as one of our new experiences. Led by a real psychic and medium, guests will use tools such as dowsing rods, temperature guns and EMF readers to communicate with the spirits who haunt the old cholera cemetery.

Haunted Montreal is pleased to announce that our public season of ghost tours is in full operation! These include Haunted Mountain, Haunted Griffintown, Haunted Downtown and the new Haunted Pub Crawl! Tickets are on sale!

Our new Haunted Pub Crawl is led by a professional ghost storyteller and visits three haunted bars. Starting at McKibbin’s Irish Pub in Downtown Montreal on Bishop Street, guests not only learn about many of the haunted drinking establishments in the city, but also hear Montreal’s most infamous ghost stories.

While sipping suds, guests enjoy haunted pubs, spine-tingling Montreal ghost stories and learn about the historical forces that transformed the ancient Indigenous island of Tiotà:ke into Ville-Marie, an austere French colony founded by Catholic evangelists.

After the British invaded, the city became a booming financial center and crime hub, a site of violent rebellion and subversive revolution and finally into Canada’s most haunted city.

Clients hear the paranormal tales behind mysterious McKibbin’s Irish Pub, the famous Sir Winston Churchill, funeral-home-cum-discotheque Club Le Cinq and, of course, Hurley’s Irish Pub, where a ghost known only as the Burning Lady haunts the establishment.

The ghost storyteller regales guests with Montreal’s most deranged and infamous ghost stories, including Simon McTavish, a Scottish fur baron known to toboggan down the slopes of Mount Royal in his own coffin, the ghost of John Easton Mills, Montreal’s Martyr Mayor who perished while tending to typhus-stricken Irish refugees during the Famine of 1847, and Headless Mary, the ghost of a Griffintown prostitute who was decapitated by her best friend in the shantytown in 1879. She returns every 7 years to the corner of William and Murray Streets, still looking for her head!

Join Haunted Montreal on this unforgettable pub crawl, where you can drink some spirits with a spirit, all the while learning about the city’s deranged history and hearing spine-tingling local ghost stories!

For full details, including a description, the starting location and schedule, please visit our new web page! Join us at 3 pm any Sunday of the year for a haunted pub crawl in English or at 4 pm in French! Tickets are now on sale!

Haunted Montreal also offers private tours and pub crawls for company outings, school groups, bachelorette parties and all types of gatherings. Please contact info@hauntedmontreal.com to organize a private tour.

We are also pleased to promote a book called Macabre Montreal.

Written by Mark Leslie and Shayna Krishnasamy, it is a “collection of ghost stories, eerie encounters, and gruesome and ghastly true stories from the second most populous city in Canada.

The authors write:

“Montreal is a city steeped in history and culture, but just beneath the pristine surface of this world-class city lie unsettling stories. Tales shared mostly in whispered tones about eerie phenomena, dark deeds, and disturbing legends that take place in haunted buildings, forgotten graveyards, and haunted pubs. The dark of night reveals a very different city behind its beautiful European-style architecture and cobblestone streets. A city with buried secrets, alleyways that echo with the footsteps of ghostly spectres, memories of ghastly events, and unspeakable criminal acts.”

With the introduction written by Haunted Montreal, Macabre Montreal is a must-read for anyone interested in Montreal’s dark side.

Haunted Montreal would also like to thank all of our clients who attended a ghost walk or haunted pub crawl recently!

If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page, something that helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours. If you have any feedback, please email us at info@hauntedmontreal.com so we can improve our visitor experience.

Lastly, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list on the top right of this page.

Coming up on August 13: Jean St. Père’s Talking Head

According to Montreal’s first historian, Dollier de Casson, in the autumn of 1657, a notary named Jean St. Père was killed by Oneida warriors while laying thatch on a roof. The warriors then cut off his head, and took it away to the other side of the river. De Casson explains that the decapitated head of Jean St. Père began insulting the warriors in the Oneida language, something he had not spoken while he was alive. In retaliation, the head was scalped, the skull crushed and flesh peeled away and discarded. Unfortunately, even the scalp kept on berating the warriors in one of the first pieces of recorded “History” in what is today Montreal.

Donovan King is a postcolonial historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbott College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec).

What an incredible learning experience this was reading Blog #47! This being my first, I’ll have to go back and read the others.

Such an easy read, kept me intrigued and interested to hear all the history in this beautiful city. It has fired me up to jump on the band wagon to enforce change, right the countless wrongs that have gone on forever! The time is now and learning from people like Donavan King, Dr Myrna Lashley and Nakuset, I will help them in whatever way I can❤️