While noted for their historical charm and timekeeping abilities, some of Montreal’s clocks are reputed to be haunted. Most of Montreal’s haunted clocks are located on St. James Street, an area associated with the extreme desecration of French colonial cemeteries by various financial corporations.

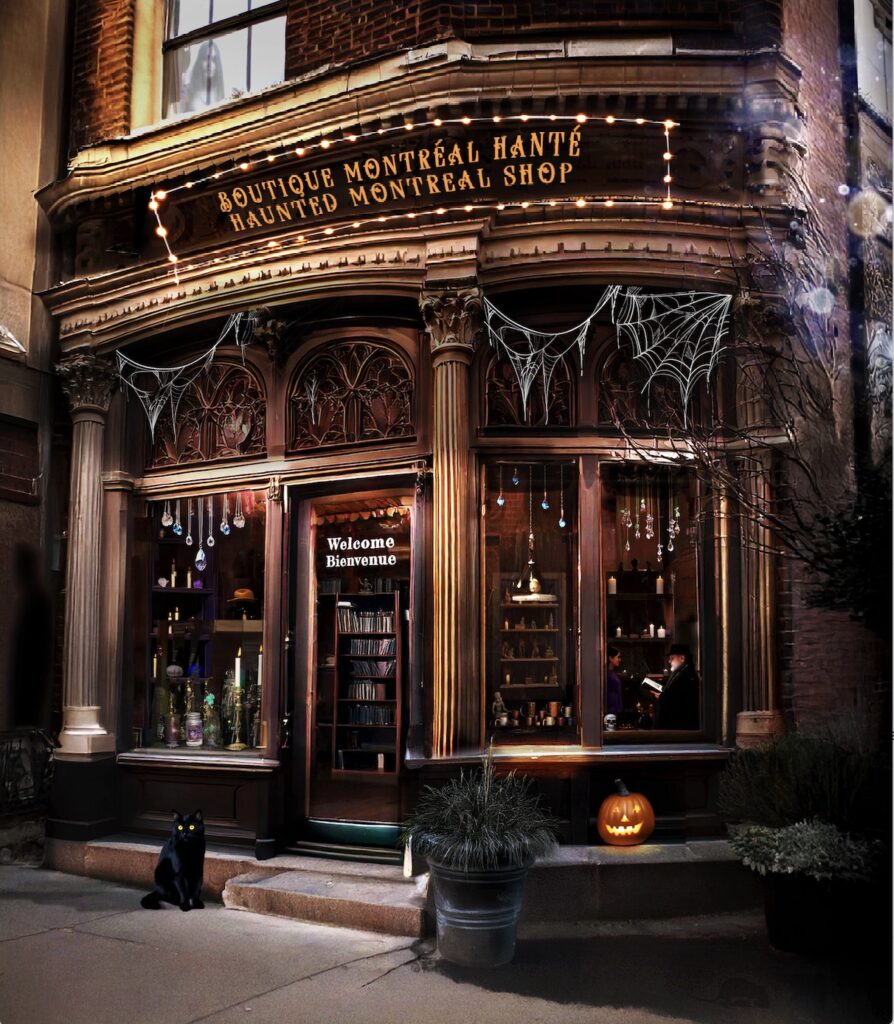

Welcome to the one hundred and twentieth installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog!

With over 600 documented ghost stories, Montreal is easily the most haunted city in Canada, if not all of North America. Haunted Montreal dedicates itself to researching these paranormal tales, and the Haunted Montreal Blog unveils a newly researched Montreal ghost story on the 13th of every month!

This service is free and you can sign up to our mailing list (top, right-hand corner for desktops and at the bottom for mobile devices) if you wish to receive it every month on the 13th! The blog is published in both English and French!

We are pleased to announce a new tour as part of our upcoming Hidden Histories series!

The Colonial Secrets of Old Montreal Walking Tour is in its final testing phase and free tickets are available this upcoming Friday and Saturday at 1 pm! The test phase is in English and tours in French will follow soon.

After testing is finished, this tour and others such as the Irish Famine in Montreal Walking Tour will be offered on various afternoons for only $20! Stay tuned to this website or our Facebook page for upcoming tours!

These tours will all be under the umbrella of Hidden Montreal, our soon-to-be-born sister company.

Haunted Montreal’s season of public outdoor ghost tours is now in full swing and tickets are on sale! These include Haunted Old Montreal, Haunted Mountain, Haunted Downtown and Haunted Griffintown. Paranormal Investigations include Old Sainte-Antoine Cemetery and Colonial Old Montreal.

We are also running our Haunted Pub Crawl every Sunday at 3 pm in English. Tours in French happen on the last Sunday of every month at 2 pm.

To learn more, see the schedule at the bottom of our home page and see more details in the Company News section below!

Private tours for all of our experiences (including outdoor tours) can be booked at any time based on the availability of our actors. Clients can request any date, time, language and operating tour. These tours start at $235 for small groups of up to 8 people.

Email info@hauntedmontreal.com to book a private tour!

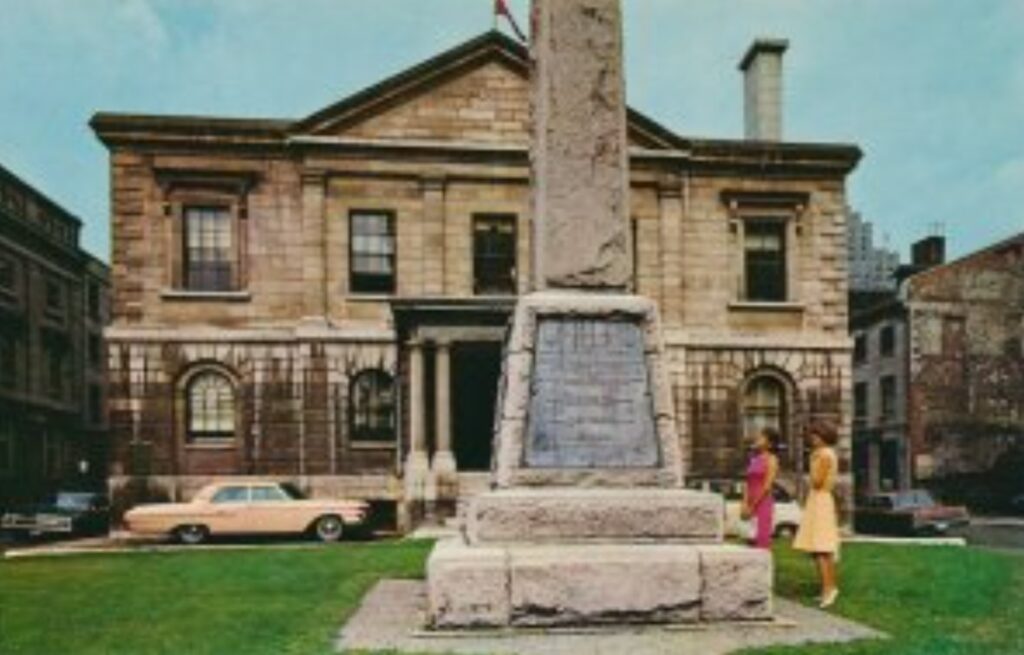

This month we examine Place Royale, one of the most deranged and haunted public squares in Old Montreal and its ghosts.

Haunted Research

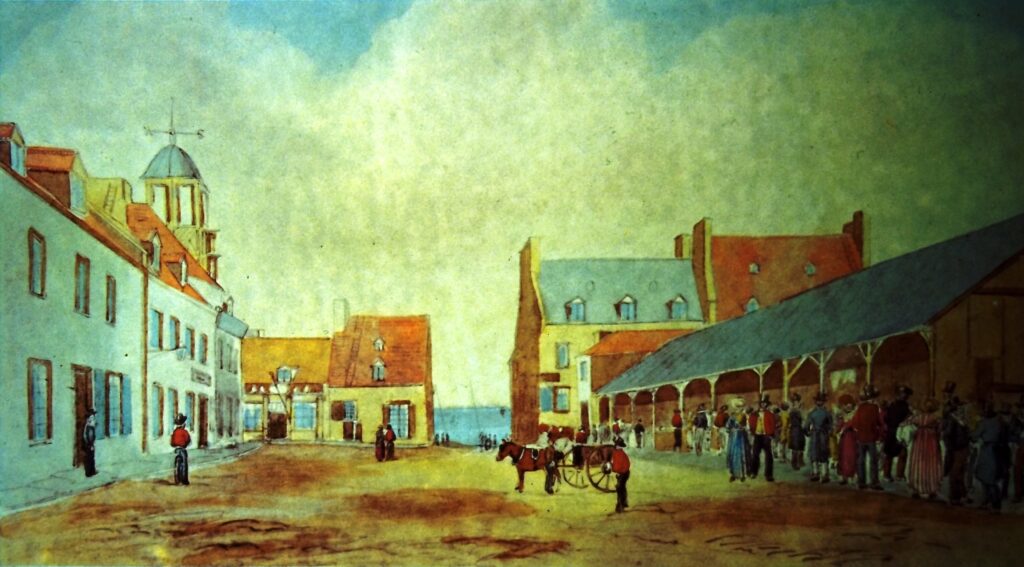

Place Royale is an unassuming and overlooked historic square in Old Montreal that hides many dark, colonial secrets. Known as the Place du Marché during the French regime, the marketplace was essentially the town square for well over a century. Hosting markets on Tuesdays and Fridays, it was also known as a site of horrific public torture, punishment and execution.

While today the site looks banal and excludes its own history in public commemoration, Place Royale is considered one of the most haunted sites in Old Montreal.

The most common ghost sighting on the square is that of a miserable drummer boy who appears to be tearing up or crying. A look at the history of the Place Royale may help reveal the identity of this forlorn apparition.

For thousands of years before the French began colonizing the island in 1642, the site where Place Royale exists today was a well-frequented area because it was at the mouth of a creek. With the canoe as the main form of transportation, creeks provided access to the inner parts of the island and could be used to avoid dangerous rapids in the river.

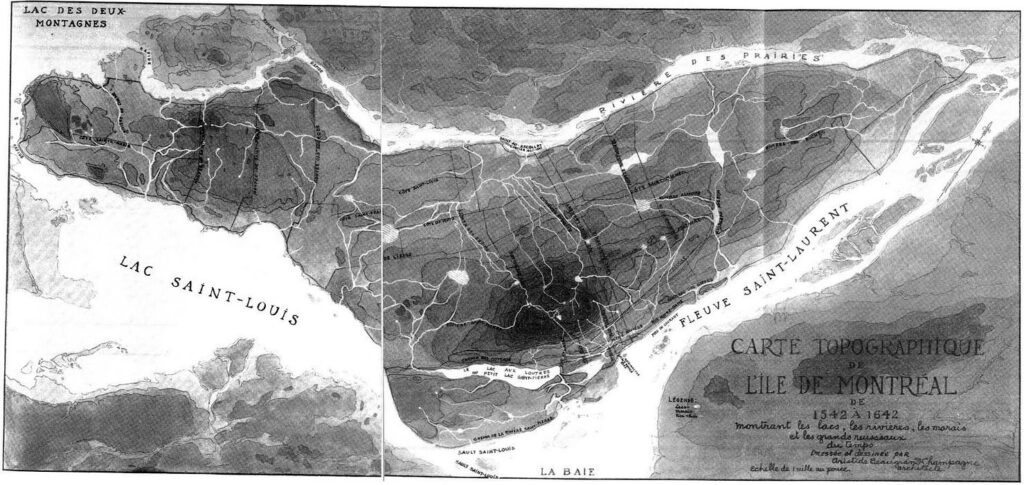

Before colonial expansion, the island had a vast network of inland streams, marshes and lakes.

These waterways were used by various First Nations as internal transportation routes. Coupled with portages and other trails, it was possible to move efficiently around the island.

The mouths of these waterways were also popular areas to encamp, conduct trade, and meet others. These creeks were all very well-known landmarks.

When French explorer Jacques Cartier claimed all indigenous territories in 1534 by planting a cross into the ground in modern-day Gaspé, the King considered all the lands to be his. French authorities began making plans to colonize what they considered to be “New France”.

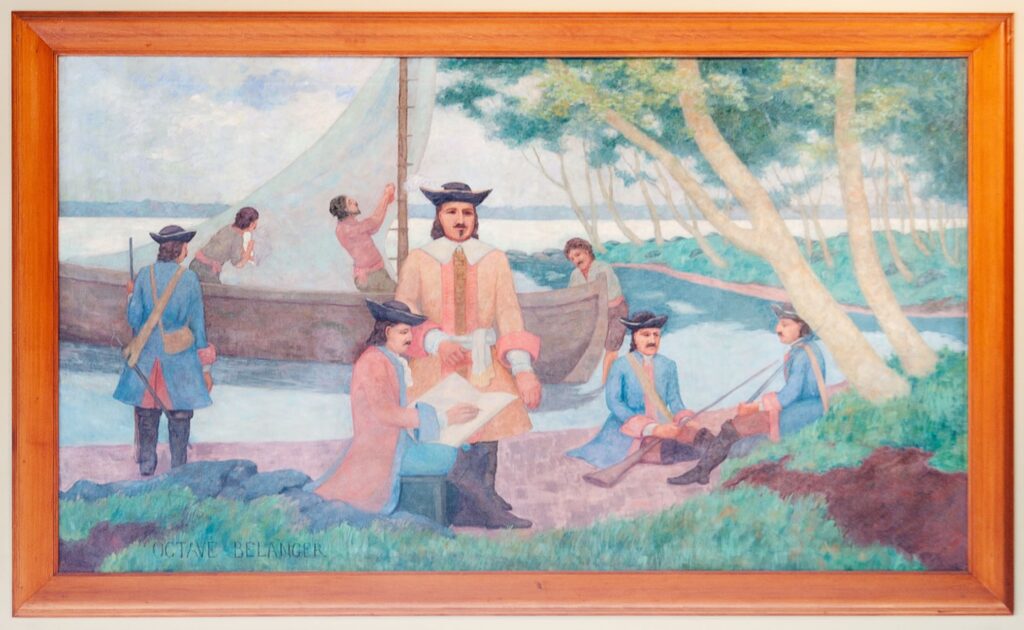

Interest in the modern-day Place Royale began in 1611, when French colonist Samuel de Champlain visited Montreal Island to create a colonization plan. He selected the site because it was located before the impassible rapids to the west and had a good harbour. It also featured a large meadow which could be strategically fortified in a triangular section which was contained within natural defenses of the river, creek and marshlands.

Champlain named the spot the Place Royale and settled there from May 28 to June 13, 1611. He ordered some trees be cut down and planted two gardens. He was was pleased when the seeds thrived in the fertile soil. He also had an earthen wall built, intending to see how it would last through the winter. He saw the area as an ideal place for a trading post and future French colony.

The French would not return to the meadow until May 17, 1642, when three colonial ships arrived under the command of Paul de Chomedey, the Sieur de Maisonneuve. Sponsored by “The Notre-Dame Society of Montreal for the Conversion of the Savage Peoples of New France”, de Maisonneuve chose the site for his Ville-Marie colony. His mission was to build a fort and a hospital. Allegedly, God had demanded this to the brainchild of the operation, Jérôme le Royer de la Dauversière.

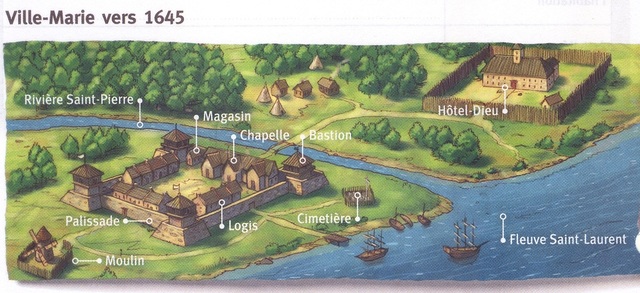

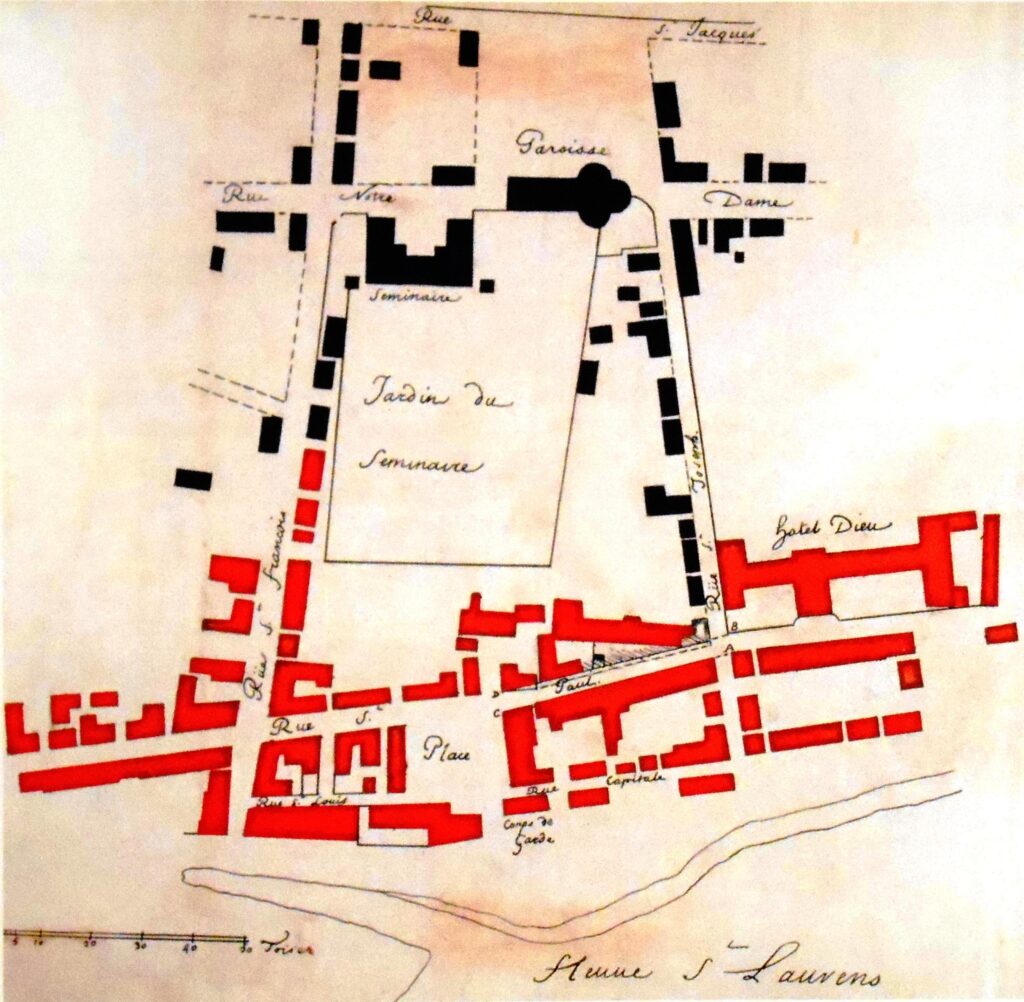

After claiming the island as their own and holding a Catholic Mass, the colonists began constructing Fort Ville-Marie on the site of today’s Pointe-à-Callière Archaeology Museum. Across the creek, which the colonists named the St. Pierre River, the Hotel-Dieu Hospital would be constructed.

Today’s Place Royale was initially part of the Ville-Marie commune, a strip of land granted to residents for grazing animals.

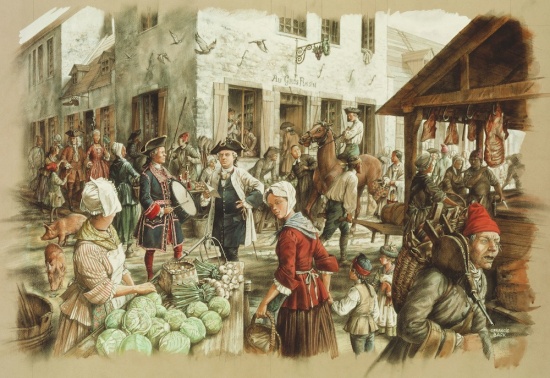

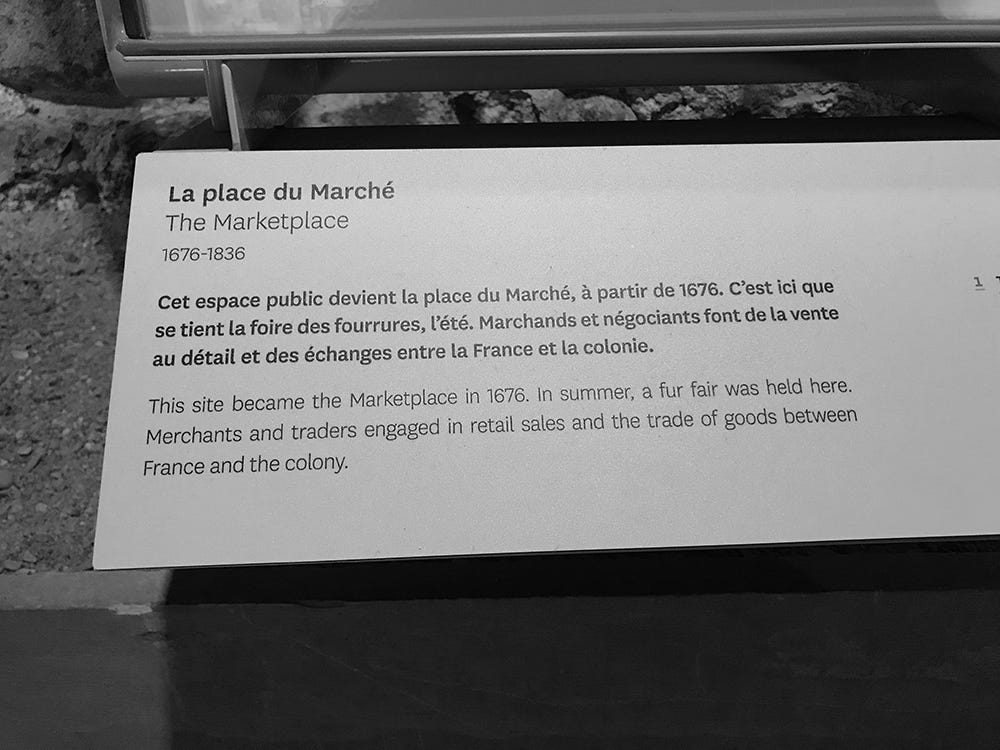

In 1676, a marketplace was established on the eastern bank of the creek. The French called it the Place d’Armes and began using it for military drills and hosting public markets every Tuesday and Friday from dawn to 11 a.m.

Here colonists could buy and sell foodstuffs and wares of various types.

There were also occasional slave auctions on the site, where French colonists could sell or purchase Black and Indigenous peoples forced into slavery.

Additionally, the marketplace was a centre of communications between colonial authorities and settlers. A royal drummer would draw a crowd by hammering on their drum before making important public announcements and sharing official news. Those in attendance could then spread the information to other colonists.

News might include royal edicts and religious proclamations, colonial developments, information about warfare and the schedule for public humiliation, torture and executions.

In “New France”, crime was seen as a dangerous threat to the existence of the colonial project. Public punishment and live executions were used as a deterrence to warn others to obey the law. Under the French Regime, there were four major types of crime:

Crimes against the State: treason, sedition, smuggling, embezzlement, counterfeiting, and resisting a legal officer.

Crimes against Property: theft, arson, concealment of stolen goods, and desertion of servants – or slaves.

Crimes against the Person: murder, manslaughter, abortion, infanticide, dueling, defamation, poisoning, rape and suicide.

There were also Crimes against the Church, or moral crimes, that were the most serious of all: adultery, bigamy, prostitution, homosexuality, sorcery, and blasphemy.

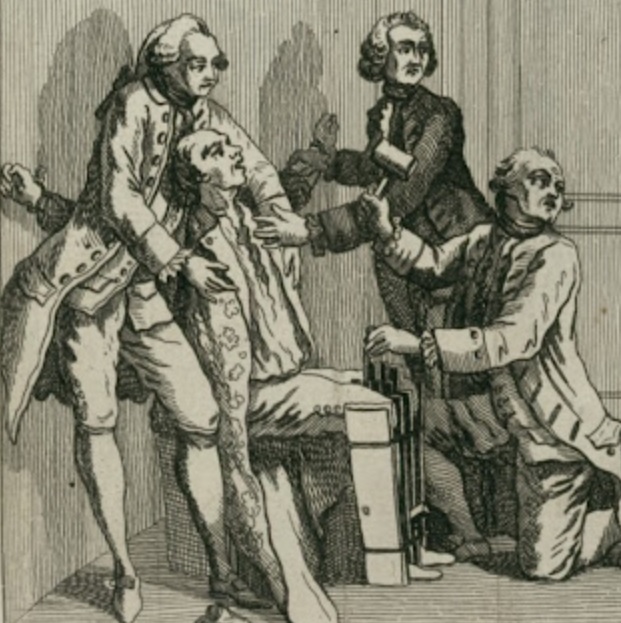

Anyone accused of any of these crimes was arrested and brought to the jail before a man known as Le Bourreau, the torturer. His job was to obtain confessions.

He produced a device known as Le Brodequin, the Spanish Boot: two planks of wood attached to either side of the lower leg and tied around tightly with rope. He always began with what was known as la question ordinaire, the ordinary question: four questions designed to get the accused to admit to their guilt.

Armed with four thick wedges, he would insert the first between the boards. If the prisoner refused to confess to the alleged crime, he would hammer it in!

Most prisoners confessed after the first or second wedge. Once the boot was removed, marrow often oozed from the crushed bone through the split wounds.

For those who endured all four wedges, they were returned to their prison cell where usually they expired during the night. If they were still alive the next morning, the torturer would ask la question extraordinaire, but instead of using four wedges, he always used eight.

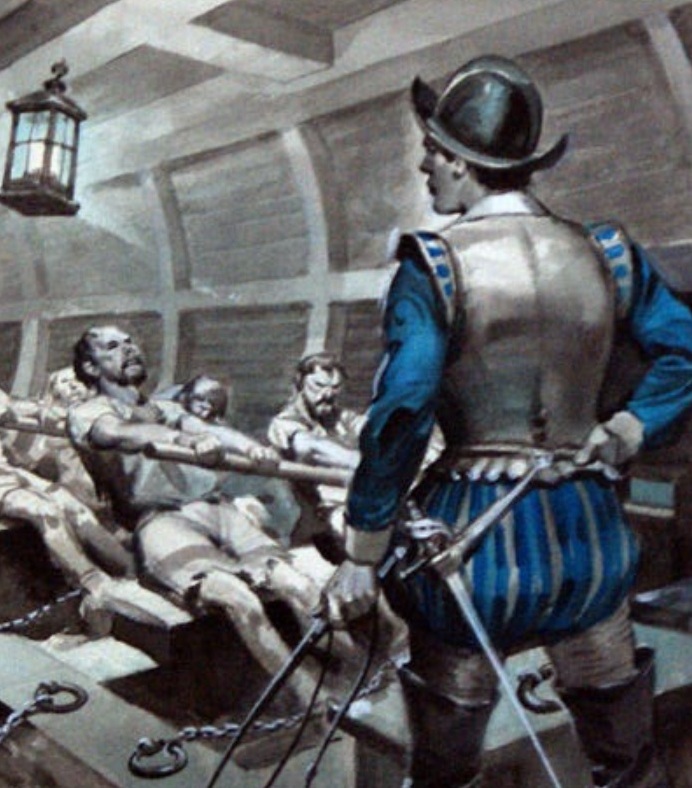

Once a confession was obtained, a punishment was established by the judge. This could include everything from fines, public flogging and branding with a red-hot fleur-de-lis symbol to banishment, being sent to row the King’s galleys and public execution.

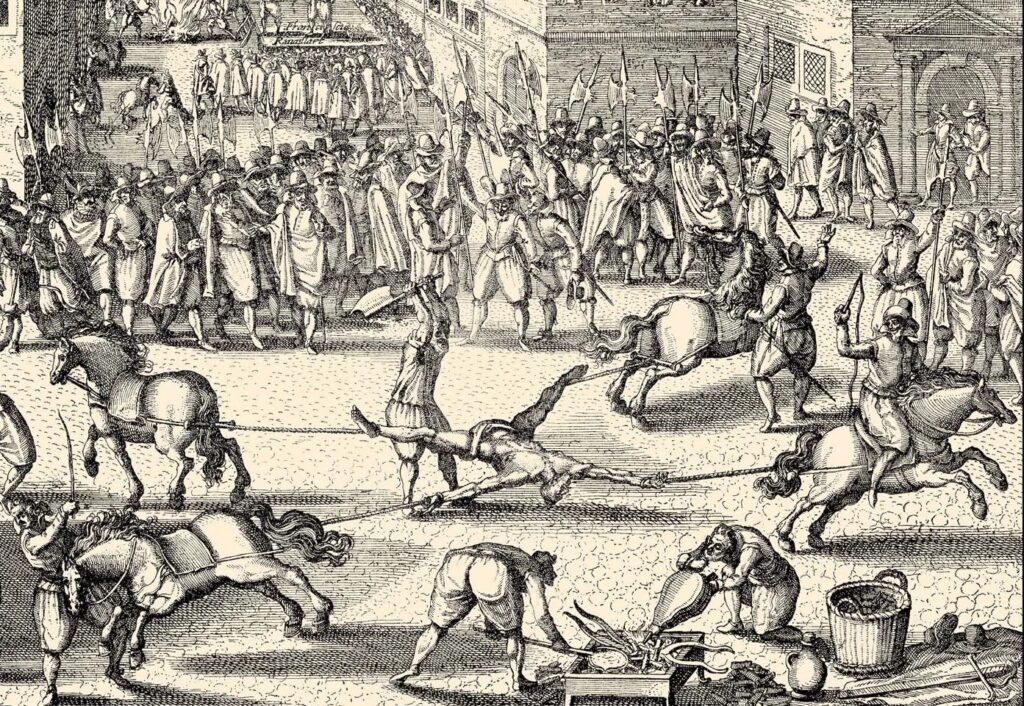

The criminal was dressed in a long, white robe known as a chemise. A sign was placed dangling around the neck with the word of the crime. The criminal was then hoisted onto the back of a horse-drawn garbage cart – and was wheeled throughout the city for all to see the condemned.

The first place they would take the criminal was to the front doors of the church. There they had to get down on their broken knees for their amende honorable – to beg forgiveness from the King of France – and God himself.

The criminal was then placed back onto the garbage cart and was wheeled away to face punishment. For those being executed, they were taken to the scene of the crime, or by default, the Place d’Armes (later renamed the Place du Marché).

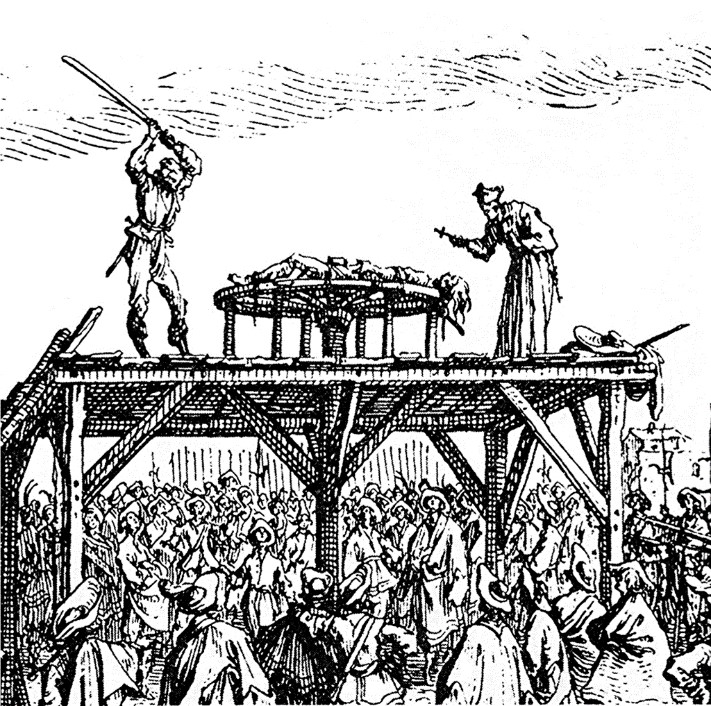

It was there that criminals were either hanged by the neck until dead, burnt alive at the stake or broken alive on a torture wheel. A torture wheel is a horizontal wheel with a pole going into a scaffold in the ground.

The torturer spun the wheel and then used a large hammer to smash in the limbs, one by one, through the gaps in the wheel. This process was repeated several times per limb, and once the criminal’s bones were smashed apart, they were left to die with their “face turned up to the sky”.

For the most serious crimes of all, they always would always draw and quarter the criminal. They lay the criminal in the center of the square and tied ropes to the arms and legs. These ropes were fed to the four corners of the square where they were attached to horses.

When the torturer gave the signal, the horses began pulling the criminal apart. The torturer would then use his sword to slice open their belly, scattering the intestines across the square for the enjoyment of all the colonists.

On June 19, 1721, during a military drill on the Place d’Armes, soldiers fired a volley into the air to celebrate the Feast of Corpus Christi. A misfired bullet hit the Hotel-Dieu Hospital and triggered a devastating fire. The inferno destroyed half of Ville-Marie. The Place d’Armes, hospital and 171 homes were all reduced to ashes.

Shortly thereafter, an ordinance was issued that all new houses were to be built exclusively with stone instead of wood.

The military drills were also relocated to the square north of the parish church, which was baptized the new Place d’Armes. The original square established in 1676 was rebuilt and given the name Place du Marché.

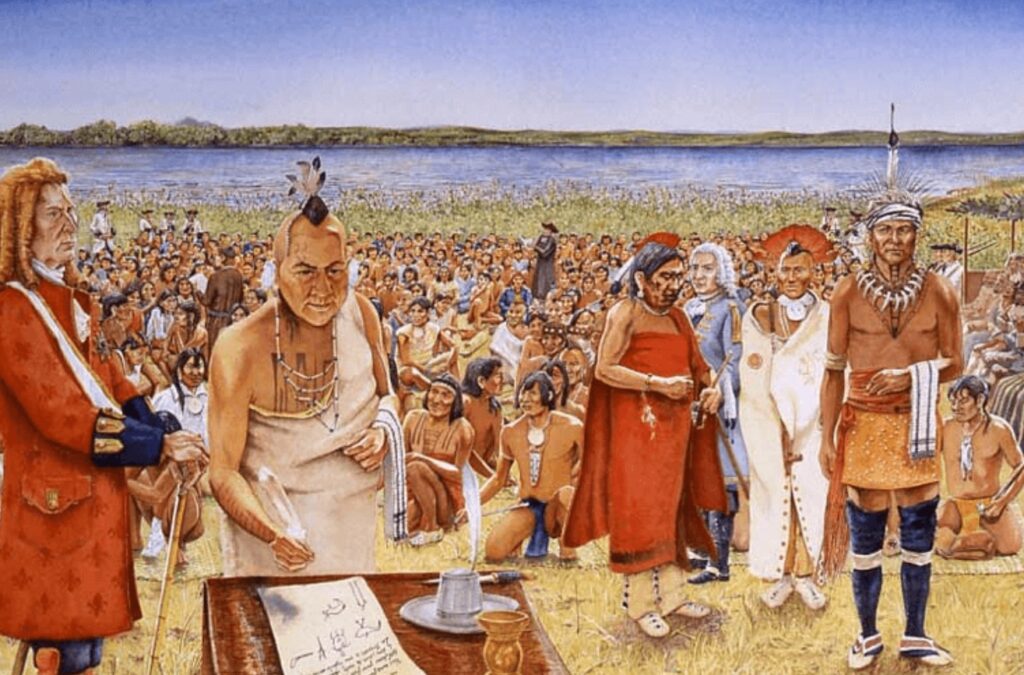

In 1701, the square was instrumental as a major gathering of dozens of First Nations who came to negotiate a peace treaty with the French colonists. Known as The Great Peace of Montreal, the treaty ended hostilities and opened up the market to large-scale fur trading.

In 1760, the city capitulated to the British after being surrounded by thousands of redcoats under the command of General Jeffery Amherst, effectively putting and end to the “New France” colonial project.

In 1786, the British justices of the peace decided that the market would be laid out as a double row of 38 stalls in a U-shape. That same year, the Place du Marché became the first area to be paved after Montreal residents raised funds through a public subscription.

As the British expanded the city and port, it soon became evident that the market square was too small for the increase in commerce.

In 1808, the New Market (Place Jacques-Cartier) was established further to the east. The “Old Market” (Place du Vieux Marché) was reorganized and reduced to a single row of 14 stalls.

In 1836, the government of Lower Canada expropriated the old market square and built the Customs House in the center. The southern part of the square was redesigned with trees, wrought iron fences, and a fountain. The British renamed it “Customs Square” (square de la Douane).

While no longer a marketplace, the square was still busy with merchants paying various tariffs and fees to the British government’s customs officers.

In 1892, the square was renamed yet again for the 250th anniversary of the founding of Montreal. “Customs Square” was rebranded as “Place Royale” (even though the original Place Royale was located across the street where the Archaeology Museum now exists).

In 1940, municipal authorities removed the fountain and moved a tall granite obelisk to Place Royale which commemorates the first French colonists to settle Ville-Marie. Known as The Pioneer’s Obelisk, it was originally unveiled on the Place d’Youville in 1893 after being commissioned for the 250th anniversary the year earlier.

The obelisk was returned to its original location in 1982 to facilitate a major archaeological dig under the Place Royale and surrounding areas.

The purpose of the dig, which ended in 1991, was to preserve archaeological remains from the original colony and to highlight them underneath Montreal’s new Pointe-à-Callière Archaeology Museum.

As part of the construction of the museum, Place Royale was rebuilt as an “archaeological crypt”. The ground-level of the square was raised by several feet and encased in granite with a series of steps leading to the platform.

This was done to allow tourists below to navigate the ruins below. Small models of the original Place du Marché over the years were installed within the crypt for visitors to enjoy.

The Pointe-à-Callière Archaeology Museum opened in 1992 for the 350th anniversary of the city, with Place Royale and its crypt included in its complex.

Since then, there has been a lot of criticism about the banal look and feel of the redeveloped Place Royale. For example, in 2010 Jessa Alston-O’Connor wrote “What Lies Beneath: Erasure and Oppression at Place Royale, Montreal”. The author states:

“The museum presents this square as a site of collective history and pride. However, research into the site reveals accounts of torture, public executions, and a history of slavery in Montreal and New France all relating to Place Royale. These events occurred at the square during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries but have been erased from the visual and historical narratives of this site.”

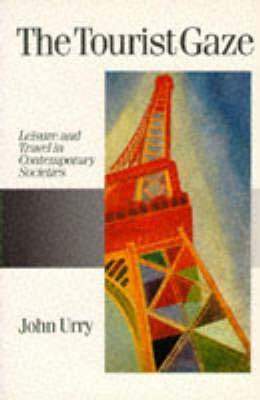

O’Connor goes on to argue that the museum “has rendered controversial histories largely invisible,” thus creating a whitewashed narrative for the “tourist gaze.”

Discussed in John Urry’s 1990 book The Tourist Gaze, the idea is that those who design touristic spaces can choose which narratives to focus on and which ones to erase.

This concept applies to the architecture, commemorations, museum displays and performative elements.

For example, the museum hosts the “Pointe-à-Callière’s 18th Century Public Market” every August. Their website claims:

“The Museum brings back to life Montréal’s very first marketplace under the French Regime. One of Pointe-à-Callière’s main events, put on every year in August in the area around the Museum, the Public Market is a magnificent historical re-enactment. There are stalls, musicians, artisans and historical figures reproducing period scenes with stunning authenticity: There’s no doubt you’ll feel like you’ve been instantly transported back to the days of our ancestors.”

However, tourists visiting the 18th Century market re-creation will never see any signs of slavery, torture, execution or other erased history. Instead, they will be treated to colonial military drills, merchants dressed in period costume and other similar re-enactments. In short, all colonial horrors have been rendered invisible on the Place Royale.

When a contested space has been so compromised by the “tourist gaze”, often the only way people can learn the truth of a site is through its ghost stories. As a place of colonial atrocities, Place Royale has been associated with dozens of ghost stories over the centuries. Many of these tales are related to the execution of innocents, deranged soldiers and tortured slaves.

For example, an episode of Creepy Canada mentions the ghosts of a man named Vallière who was wrongfully imprisoned and tortured. He committed suicide with the chains that bound him to the prison wall.

His spirit has been seen wandering St. Paul Street and the Place Royale on many occasions.

The most common sighting is the spirit of a desolate drummer boy dressed in a French colonial unform. The encounter usually begins with the sound of a rolling drum, which is usually out of rhythm.

Then, the ghost of the drummer boy materializes. He appears to be very upset and has been described as teary-eyed and sometimes weeping. He usually stops playing his drum before falling to his knees in despair. When approached, he always vanishes into thin air.

He is not to be mistaken for the actors dressed in make up and spooky costumes who carry out ghost tours on the site most evenings in the warmer seasons.

While most people have no idea who this ghostly apparition might be, Haunted Montreal has done some deep research and found a probable answer.

Just six years into the colony’s existence, in 1648 Ville-Marie’s military drummer and public announcer was arrested after being accused of “crimes of the worst kind,” namely a homosexual relationship.

This was first recorded mention of homosexuality among Europeans.

According to the Journal of the Jesuit Fathers of September 1648:

“About this time, there was brought from Montreal a drummer, Convictus crimine pessimo (convicted of a crime of the worst kind), whose death our Fathers who were at Montreal opposed, sed occute; he was then sent hither and put in the prison. It was proposed to him, so that he might at least escape the galleys, to accept the office of executioner of Justice; he accepted it, but his trial was first disposed of, and then his sentence was commuted.”

In other words, Jesuit authorities reduced his sentence from execution to being enslaved to rowing on the King’s galleys. He was then offered the role of public executioner to avoid enslavement, which he accepted, probably reluctantly.

While historians debate about the name of the unfortunate drummer boy and his male lover, details are sketchy. The lover may have escaped because he was never arrested. While some historians say the drummer boy’s name has been lost to history, others such as Pierre Hurteau and Patrice Corriveau called him “René Huguet dit Tambour.”

While little is known about him, historians do know that his first execution was of a girl of 15 or 16 who was convicted of theft.

After that, the paper trail runs cold.

It is also known that in 1653, the colony was looking for a new executioner. The fate of the drummer boy is unknown, although there is speculation he may have committed suicide or escaped the colony.

The psychological torture endured by the drummer boy may have very well resulted in his suicide. Due to his forbidden sexuality, he was transformed from a well-respected military drummer and public announcer into a torturer and executioner, the most despised position in the colony.

After having to torture and execute a teenaged girl for an alleged theft, he may have suffered from suicidal thoughts.

Whether he escaped the colony or died by suicide, only one thing is known: his miserable ghost returns to haunt the Place Royale. His ghostly appearance sheds a glimmer of the horrific colonial history that unfolded in an otherwise whitewashed public square.

Company News

We are pleased to announce a new tour as part of our upcoming Hidden Histories series! The Colonial Secrets of Old Montreal Walking Tour is in its final testing phase and free tickets are available this upcoming Friday and Saturday at 1 pm!

After testing is finished, this tour and others such as the Irish Famine in Montreal Walking Tour will be offered on various afternoons for only $20! Stay tuned to this website or our Facebook page for upcoming tours!

These tours will all be under the umbrella of Hidden Montreal, our soon-to-be-born sister company.

Our season of public outdoor ghost tours is now in full swing and tickets are on sale! These include Haunted Old Montreal, Haunted Mountain, Haunted Downtown and Haunted Griffintown. Paranormal Investigations include Old Sainte-Antoine Cemetery and Colonial Old Montreal.

We are also running our Haunted Pub Crawl every Sunday at 3 pm in English. For tours in French, these happen on the last Sunday of every month at 2 pm.

Private tours for any of our experiences (including outdoor tours) can be booked at any time based on the availability of our actors. Clients can request any date, time, language and operating tour. These tours are based on the availability of our actors and start at $235 for small groups of up to 8 people.

Email info@hauntedmontreal.com to book a private tour!

You can also bring the Haunted Montreal experience to your office party, house, school or event by booking one of our Travelling Ghost Storytellers today.

Hear some of the spookiest tales from our tours and our blog told by a professional actor and storyteller. You provide the venue, we provide the stories and storyteller. Find out more and then contact info@hauntedmontreal.com

Our team also releases videos every second Saturday, in both languages, of ghost stories from the Haunted Montreal Blog.

Hosted by Holly Rhiannon (in English) and Dr. Mab (in French), this initiative is sure to please ghost story fans!

Please like, subscribe and hit the bell!

In other news, if you want to send someone a haunted experience as a gift, you certainly can! We are offering Haunted Montreal Gift Certificates through our website and redeemable via Eventbrite for any of our in-person or virtual events (no expiration date).

Lastly, we have decided to close our online shop due to low sales and high maintenance costs. It will only be open from October to December in the near future.

Haunted Montreal also has temporarily altered its blog experience due to a commitment on a big writing project! The book is titled Haunted McGill, and is authored by yours truly, Donovan King! Our publisher is The Stygian Society.

Until publication in 2026, new stories at the Haunted Montreal Blog will be offered every two months, whereas every other month will feature an update to an old story.

As always, these stories and updates will be released on the 13th of every month!

Haunted Montreal would like to thank all our clients who attended a ghost walk, haunted pub crawl, paranormal investigation or virtual event!

If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page and/or on Google Reviews – something that really helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours.

Lastly, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list.

Coming Up on September 13: Update on Montreal’s Mysterious River Monsters

In May, 2020, Haunted Montreal published a blog about Montreal’s Mysterious River Monsters. Since then, the waters surrounding the city have witnessed more bizarre sightings and situations involving unknown and dangerous marine creatures. The most notable case occurred in June 2024, when an eight-year-old boy was attacked by something predatory in the enclosed waters of Jean Doré Beach. He sustained several deep gashes in his leg that required stitches. While some scientists think the predator was a muskie (a large fish with sharp teeth), others believe it was it was a river monster who had somehow entered the waters of the enclosed beach in search of its next meal.

Author:

Donovan King is a postcolonial historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbott College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec). He is also a certified Montreal Destination Specialist.

Translator (into French):

Claude Chevalot holds a master’s degree in applied linguistics from McGill University. She is a writer, editor and translator. For more than 15 years, she has devoted herself almost exclusively to literary translation and to the translation of texts on current and contemporary art.

Fascinating as usual,

Your knowledge runs deep throughout Montréal and area

I am always saddened by how little I was taught growing up in Montréal about our history!

Congratulations on your 120th!

Cheers!!