This month we provide an update on the Hôpital de la Miséricorde and analyze controversial plans by Hydro-Québec to integrate an electricity substation into the haunted site. The ghost-ridden Hôpital de la Miséricorde has been empty for years and is starting to crumble. Located on prime real estate in Downtown Montreal...

Welcome to the forty-eighth installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog!

With over 300 documented ghost stories, Montreal is easily the most haunted city in Canada, if not all of North America. Haunted Montreal is dedicated to researching these paranormal tales, and the Haunted Montreal Blog unveils a newly-researched Montreal ghost story on the 13th of every month! This service is free and you can sign up to our mailing list (top, right-hand corner) if you wish to receive it every month on the 13th!

We are also pleased to announce that all of our ghost tours are now operating and tickets are on sale! These include Haunted Mountain, Haunted Griffintown, Haunted Downtown and the new Haunted Pub Crawl!

We are also thrilled to invite you on August 17th to Hurley’s Pub for the official launch party of Griffin Tours, the new company that will combine Haunted Montreal’s tours with other exciting offerings, such as Irish History in Montreal tours and our new Hidden Histories of Montreal walking tour! Details below!

Our August blog examines the bizarre and paranormal tale of Jean Saint-Père’s talking head, as reported by Montreal’s first historian, François Dollier de Casson, and other prominent figures in “New France”.

HAUNTED RESEARCH

During the years of the “New France” colonial project, a lot of strange stories appeared as written by the colonizers. François Dollier de Casson, Montreal’s first “historian”, was known to write strange “history” that today would be certainly considered revisionist, if not outright delusional.

The deranged tale of Jean Saint-Père’s talking head is perhaps his most infamous.

In the early 16th century, European empires began attempting to colonize Indigenous territories in present-day North America. France’s earliest attempt to stake a claim in the new world occurred in 1534, when French sailor Jacques Cartier arrived in Chaleur Bay off the Gaspé peninsula and planted a 30-foot wooden cross to which he attached a shield bearing the fleur-de-lis and upon which he carved the words Vive le Roy de France. Citing the now-outdated Catholic doctrine of Terra Nullius, he thus tried to claim the Indigenous lands for France.

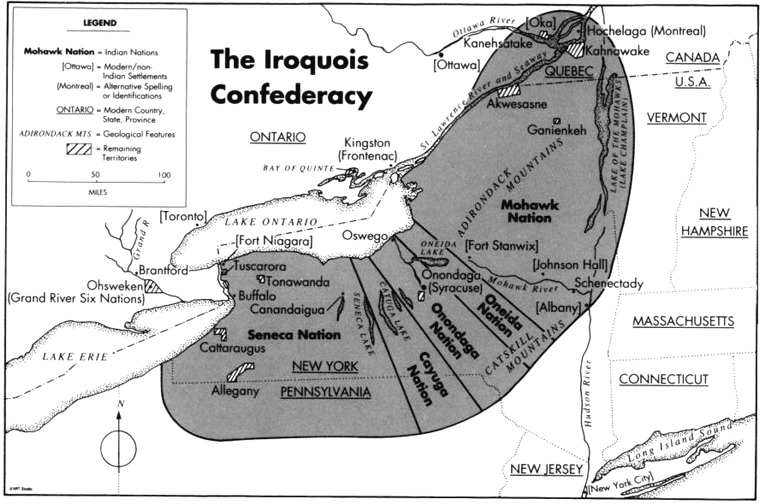

In the 1600s, the French started colonizing. The Quebec colony appeared in 1608 and Trois-Rivières in 1634. The French were tempted to colonize Tiohtià:ke, today’s Montreal island, but were worried because it was traditional Mohawk territory, and the Mohawks were not only part of a confederation of five First Nations called the Haudenosaunee, but were also considered among the best warriors in the land. The Haudenosaunee confederacy also included the Oneidas, the Onodogas, the Cayugas and the Senecas.

Meanwhile, in France, a Catholic Mystic named Jérôme le Royer de la Dauversière had a vision which he claimed came directly from God. In his vision, he imagined a New Jerusalem set up on today’s Montreal island designed to convert the Indigenous First Nations to Catholicism. He promptly founded a culturally-genocidal organization called “The Society of Notre-Dame of Montreal for the Conversion of Savages of New France” and prepared an expedition of colonization.

Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve, a soldier in his thirties, was hired to command the expedition, along with a 34-year-old volunteer nurse named Jeanne Mance and three boatloads of colonists.

When they arrived in Quebec in 1641, the scheme was not supported by the Jesuits there and even less so by Governor Montmagny, who said: “The scheme of this new company is so absurd that it would be better to call it the foolhardy enterprise.”

Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve replied with the following genocidal words:

“Sir, as it was determined by my company that I would go to Montreal, it is for me a question of honour, and you will find it good that I go up there to begin a colony, even though every tree of this island were to change into an Iroquois.”

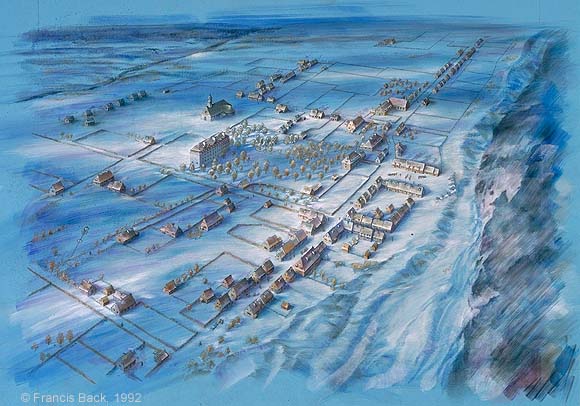

True to his word, on May 17, 1642, he established a colony called Ville-Marie on the island. Named after the Virgin Mary, the colony was intended to be a center for the erasure of Indigenous culture in favour of Catholic hegemony.

At the time, Tiohtià:ke was not inhabited, as the Mohawk First Nation had retreated into southern territory on account of European epidemics, such as smallpox, that were devastating the nation, not to mention attacks from the “Agojuda” (a word meaning “evil men”), likely the Huron First Nation.

When Mohawk scouts discovered that Tiohtià:ke had been colonized by the French, an all-out war broke out between the French and the Haudenosaunee, characterized by guerilla warfare, gruesome torture, and various kidnappings.

Returning to the Europeans documenting this war, François Dollier de Casson was born in France into a wealthy bourgeois and military family in 1636. After serving in the French Army for 3 years, he decided to study to become a priest. Once accepted into the Sulpician Order, he was deployed to “New France”, an assignment he took on with some reluctance.

When he arrived in Quebec in 1666, he was immediately appointed as a military chaplain with Prouville de Tracy, who was planning a genocidal campaign against the Mohawk First Nation, whose territory the French were attempting to colonize.

The Marquis de Tracy led a French force of 600 regulars and 600 militia and Native allies into Mohawk lands. Three hundred boats and canoes carried de Tracy’s men to the south end of today’s Lake Champlain. Once ashore, the troops marched east into the heart of Mohawk territory. The Mohawk warriors chose not to confront such a large and well-armed force and withdrew into the surrounding forest. De Tracy’s soldiers razed Mohawk villages to the ground and burnt their fields and stores of food. Although the French had not defeated the Mohawk people in battle, the invasion and subsequent scorched earth campaign triggered a deadly starvation.

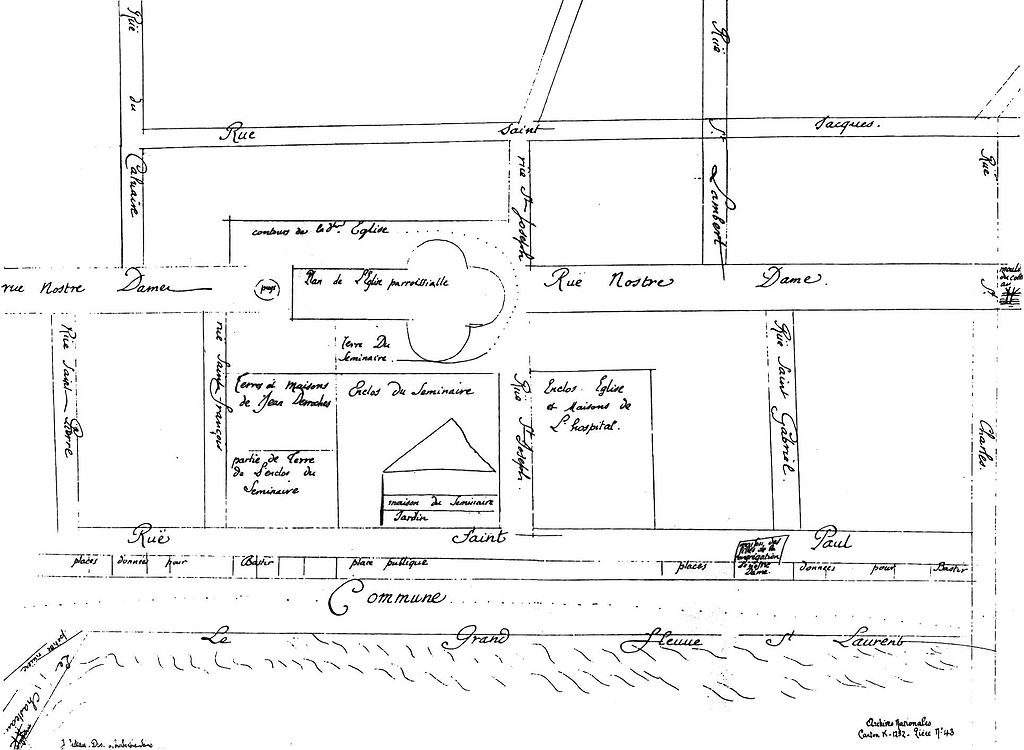

François Dollier de Casson was active as a missionary and explorer until becoming superior of the Sulpicians in “New France” in 1671. He also contributed to church architecture, served as vicar general of the diocese of Quebec and ordered the first street survey of what is now Old Montreal.

He was also one of the key figures of the first attempt to dig the Lachine Canal, in 1689, which ultimately failed.

While he was well known as a religious figure and public authority, he also appointed himself as the city’s first “historian” and wrote Histoire du Montréal, 1640-1672, Issues 1-5.

An attempt to document the life of French colonizers in the settlement of Ville-Marie, Histoire du Montréal has been criticized as a piece of historical revisionism that is so unrealistic, racist and Eurocentric that it is both unverifiable and utterly delusional in its sprinkling of “miracles” designed to bolster European hegemony at the expense of First Nations perspectives and Indigenous knowledge.

Indigenous knowledge broadly refers to indigenous ways of knowing that both guide and result from their community members’ close relationships with and responsibilities to the environment, including landscapes, waterscapes, plants, animals and others. Seen as an ancient combination of values, responsibilities, history and laws, Indigenous knowledge is vital to the flourishing of First Nations cultures. Indigenous peoples’ traditional ways of knowing and living have been refined over thousands of years of experiences and relationships with living beings and places. This oral knowledge system is remarkably stable, with Elders and knowledge-keepers passing down the knowledge to future generations.

Western or European “history”, unlike Indigenous knowledge, is unstable and under constant revision based on power-dynamics, such as religious doctrines, colonial ideologies, Euro-centricity, white supremacy and nationalisms, all of which involve the suppression and exclusion of voices of those being oppressed by these systems of domination.

For example, François Dollier de Casson relays the story of Father Le Maistre’s death in 1661 – and the subsequent “miracle” of a speaking handkerchief that refused to be stained with his blood:

“Père Le Maistre, a devout priest under Olier, came out to the Seminary at Montreal. On the 29th of August, 1661, he accompanied the harvesters into the fields of Fort St. Gabriel, a little fortified farm enclosure now within the edge of the city, where he constituted himself the guard, reciting meanwhile his breviary. He passed so near some Iroquois lying concealed in the brushwood that they, believing themselves discovered, sprang upon him with fierce war cries. Careless of peril to himself, he called out to his men to run. The savages, seeing their prey escaping, took revenge upon him, cut off his head, and carried it off in a handkerchief. But his features, say the accounts of the time, remained imprinted thereon. “What is peculiar,” they write, “is that there was no blood on the handkerchief, and that it was very white. It appeared on the upper side like a very fine white wax, which bore the face of the servant of God.” They say even that it spoke to them at times and reproached them for their cruelty, and that, in order to free themselves of this oracle which terrified them, they sold the handkerchief to the English. Hoondoroen, the murderer, became converted, and died at the mission of St. Sulpice.”

Not only is the historical analysis a case of magical-thinking, but it is also racist, revisionist and Euro-centric.

Perhaps the most infamous historical revision from François Dollier de Casson is his story about a notary named Jean Saint-Père.

Jean Saint-Père, clerk of court, notary, and syndic, came to Montreal, probably in 1643, in order “to contribute to the conversion of the Indians.” From January, 1648 he was appointed the first clerk of the court and the first notary at Ville-Marie. In 1651, he became the syndic of the Communauté des Habitants of Ville-Marie, and in 1654 he was elected “receiver of alms for the construction of the proposed church at Montreal.”

Seen as a very pious Catholic by fellow colonists, on October 25, 1657, he met his tragic fate.

At the time, there was a truce between the French and the Haudenosaunee, yet this fragile peace didn’t reflect any growing acceptance by the First Nations having the French encroaching on their land. The calm had more to do with the five nations of Haudenosaunee focusing for a while on renewed hostilities with their traditional enemies to the south. The peace would not last.

That fateful day, Nicolas Godé and Jean St. Père were on the roof of a house they were building, laying thatch. It might have been on adjoining properties owned by the two men on what is now Place d’Armes, or perhaps it was close to Point Saint Charles, where Godé also had land. As they were thatching the roof, they were visited by a small group of Oneidas. Supposedly the colonists fed the visitors before returning to work on the roof. François Dollier de Casson described the scene as such:

“This man of such stout piety [Jean Saint-Père], of so keen a spirit and all together of a judgment as excellent as we have seen here, experienced a tragic end, on October 25, 1657. While peace reigned recently between the French and the Iroquois, a group of Oneidas came to see Nicolas Godé, who was busy with his son-in-law, Jean Saint-Père and their servant, Jacques Noël, building a house. The French received the visitors very civilly, even giving them food. Coming under the guise of peace and friendship, but nourished by perfidious designs, the Iroquois waited until their guests got back on the roof to continue working, when they reached for their arquebuses and shot them, felling them like sparrows. Finishing their work, the Oneidas scalped Godé and Noël, then they cut off the head of Saint-Père, which they carried away to have his beautiful hair”.

The decapitated corpse of Jean Saint-Père was buried on the same day, in a communal grave with his two unfortunate companions after a Death Notice was published.

From here, the story gets much, much more bizarre.

Dollier de Casson, school teacher Marguerite Bourgeoys and fellow colonist Vachon de Belmont reported a bizarre denouement to the beheading incident. They claimed that while the Iroquois (a French term for the Haudenosaunee) were fleeing with their macabre trophy, the head of Jean Saint-Père began to speak “in a very good Iroquois, although, during his lifetime, Jean Saint-Père had always ignored this language”. According to the colonists, the head of Jean Saint-Père began reproaching the warriors for their deceitfulness, saying:

“You murder us, you inflict a thousand cruelties on us, you want to annihilate the French but you will not succeed. The French will one day be your masters and you will obey them. It is vain for you to struggle.”

Supposedly, the Oneidas tried throwing away the head, but it rolled back to their encampment and continued insulting the warriors. According to Dollier de Casson, the Oneida warriors put the head “sometimes in one place, sometimes another.” He claimed: “Even when they covered it to prevent it from being heard, it was no better.”

Despite efforts to hide or to bury the talking head, the vengeful voice of Jean Saint-Père continued to be heard. They finally peeled away the flesh and crushed the skull, keeping only the scalp, as the story goes. Unfortunately, even the scalp kept berating them. According to Margeurite Bourgeois, it told them: “You think you do us harm, but you send us to Paradise.”

Dollier de Casson claimed that he had heard this story from “people of good repute”, presumably René Cuillerier, who had been a prisoner of the Oneidas. Apparently it was the Oneidas themselves who had told this story to their prisoner.

It is noteworthy that there doesn’t appear to be any evidence of this story in the Indigenous knowledge held by the Elders and Knowledge-keepers of the Oneida First Nation, suggesting that Montreal’s first recorded “History” is nothing more than fanciful illusions designed to bolster the French colonists and the Catholic religion.

For more on how the colonizer culture constantly revises its “History” about Indigenous peoples, watch the Les Brutes episode (in French) called L’histoire des premières nations enseignée aux enfants, where Melissa Mollen-Dupuis, an Innu activist and educator, discusses the many revisions to Quebec’s “History” books over the years with two postcolonial activists playing students.

She points out that Indigenous people were first presented as “savages”, then as a vanished race, and now are still misrepresented in the Quebec History curriculum as “The Other” and not as a people being colonized and trying to defend themselves.

This unfortunate situation is a direct result of the Quebec Department of Education’s ongoing insistence of mis-educating the general population, including with its recently debunked “History” curriculum.

Sadly, until such a time at the Quebec Department of Education includes Indigenous history and perspectives in its curriculum, those living here will continue to be mis-educated by the constantly shifting locus of Euro-centric “history”, the same source that brought us the outlandish story of Jean Saint-Père’s talking head.

As such, readers would be wise to consider article 15.2 from the Calls for Justice from The National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, which is a message for all Quebeckers and Canadians:

“Decolonize by learning the true history of Canada and Indigenous history in your local area. Learn about and celebrate Indigenous peoples’ history, cultures, pride and diversity, acknowledging the land you live on and its importance to local Indigenous communities, both historically and today.”

It is a noble first step to begin squaring real Indigenous history with the Euro-centic revisionism that is still being taught in Quebec’s schools in 2019.

COMPANY NEWS

Firstly, a special announcement. We will be launching Griffin Tours as an umbrella company for Haunted Montreal, Irish Montreal Excursions and our new Hidden Histories of Montreal walking tour. Griffin Tours aims to bring new, 21st Century experiences to next-generation visitors and tourists. We want you to join our community and help shape the future of Tourism in Montreal!

On Saturday, August 17, we are hosting a Postcolonial Picnic and Speaker’s Corner at 2 pm in Saint Henri Park at the haunted statue of Jacques Cartier. We invite you to bring a blanket, a picnic lunch and an open mind. Those wishing to speak out against colonialism, racism, and similar topics can sign up for a 10-minute slot on the soap box. More details can be found here.

The official Griffin Tours launch event takes place the same evening at Hurley’s Irish Pub (1225 Crescent Street) starting at 6 pm. There will be live entertainment, free appetizers, a raffle and some big announcements. More details can be found here. Everyone is welcome!

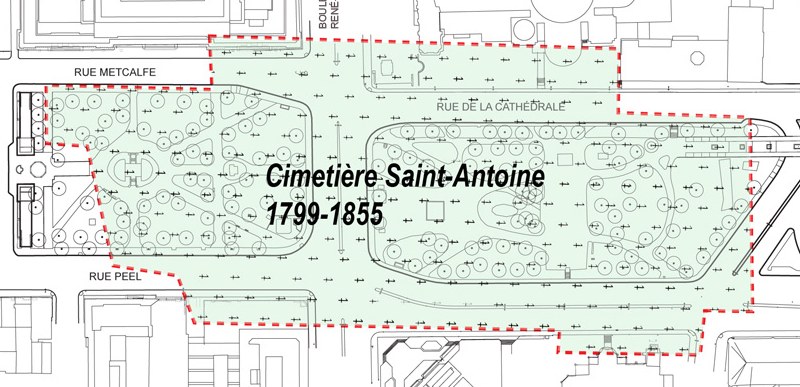

Secondly, we are in the planning stages for a Paranormal Investigation in the old Sainte Antoine Cemetery as one of our new experiences. Led by a real psychic and medium, guests will use tools such as dowsing rods, temperature guns and EMF readers to communicate with the spirits who haunt the old cholera cemetery.

Haunted Montreal is pleased to announce that our public season of ghost tours is in full operation! These include Haunted Mountain, Haunted Griffintown, Haunted Downtown and the new Haunted Pub Crawl! Tickets are on sale!

Our new Haunted Pub Crawl is led by a professional ghost storyteller and visits three haunted bars. Starting at McKibbin’s Irish Pub in Downtown Montreal on Bishop Street, guests not only learn about many of the haunted drinking establishments in the city, but also hear Montreal’s most infamous ghost stories.

While sipping suds, guests enjoy haunted pubs, spine-tingling Montreal ghost stories and learn about the historical forces that transformed the ancient Indigenous island of Tiotà:ke into Ville-Marie, an austere French colony founded by Catholic evangelists.

After the British invaded, the city became a booming financial center and crime hub, a site of violent rebellion and subversive revolution and finally into Canada’s most haunted city.

Clients hear the paranormal tales behind mysterious McKibbin’s Irish Pub, the famous Sir Winston Churchill, funeral-home-cum-discotheque Club Le Cinq and, of course, Hurley’s Irish Pub, where a ghost known only as the Burning Lady haunts the establishment.

The ghost storyteller regales guests with Montreal’s most deranged and infamous ghost stories, including Simon McTavish, a Scottish fur baron known to toboggan down the slopes of Mount Royal in his own coffin, the ghost of John Easton Mills, Montreal’s Martyr Mayor who perished while tending to typhus-stricken Irish refugees during the Famine of 1847, and Headless Mary, the ghost of a Griffintown prostitute who was decapitated by her best friend in the shantytown in 1879. She returns every 7 years to the corner of William and Murray Streets, still looking for her head!

Join Haunted Montreal on this unforgettable pub crawl, where you can drink some spirits with a spirit, all the while learning about the city’s deranged history and hearing spine-tingling local ghost stories!

For full details, including a description, the starting location and schedule, please visit our new web page! Join us at 3 pm any Sunday of the year for a haunted pub crawl in English or at 4 pm in French! Tickets are now on sale!

Haunted Montreal also offers private tours and pub crawls for company outings, school groups, bachelorette parties and all types of gatherings. Please contact info@hauntedmontreal.com to organize a private tour.

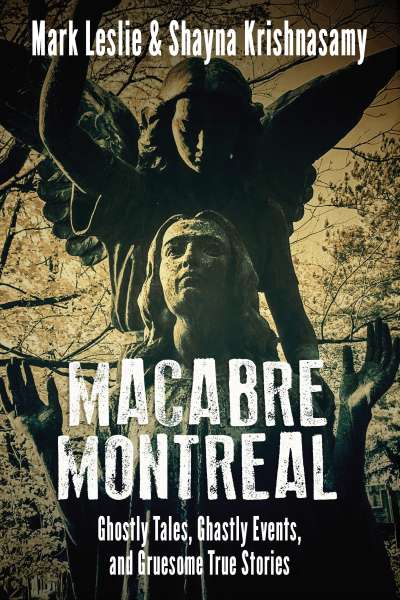

We are also pleased to promote a book called Macabre Montreal.

Written by Mark Leslie and Shayna Krishnasamy, it is a “collection of ghost stories, eerie encounters, and gruesome and ghastly true stories from the second most populous city in Canada.

The authors write:

“Montreal is a city steeped in history and culture, but just beneath the pristine surface of this world-class city lie unsettling stories. Tales shared mostly in whispered tones about eerie phenomena, dark deeds, and disturbing legends that take place in haunted buildings, forgotten graveyards, and haunted pubs. The dark of night reveals a very different city behind its beautiful European-style architecture and cobblestone streets. A city with buried secrets, alleyways that echo with the footsteps of ghostly spectres, memories of ghastly events, and unspeakable criminal acts.”

With the introduction written by Haunted Montreal, Macabre Montreal is a must-read for anyone interested in Montreal’s dark side.

Haunted Montreal would also like to thank all of our clients who attended a ghost walk or haunted pub crawl recently!

If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page, something that helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours.

If you have any feedback, please email us at info@hauntedmontreal.com so we can improve our visitor experience.

Lastly, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list on the top right of this page.

Coming up on September 13: Old Sainte Antoine Cemetery

Dorchester Square and Place du Canada in the heart of Downtown Montreal harbor a very dark secret. Lurking just below the soil are the skeletons of an estimated 70,000 Montrealers, many of them victims of cholera who were buried in mass graves during Cholera epidemics in the mid-1800s. Once known as Sainte Antoine Cemetery, the Catholic burial ground operated from 1799 until the mid-1800s. Rife with paranormal activity such as floating orbs, disembodied prayers and the sounds of screaming, the Old Sainte Antoine Cemetery is a dark and haunted stain on the city.

Donovan King is a postcolonial historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbott College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec).

This blog is super spooky and interesting