This month we provide an update on the Hôpital de la Miséricorde and analyze controversial plans by Hydro-Québec to integrate an electricity substation into the haunted site. The ghost-ridden Hôpital de la Miséricorde has been empty for years and is starting to crumble. Located on prime real estate in Downtown Montreal...

Welcome to the fiftieth installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog!

Happy Hallowe’en Season! With over 300 documented ghost stories, Montreal is easily the most haunted city in Canada, if not all of North America. Haunted Montreal is dedicated to researching these paranormal tales, and the Haunted Montreal Blog unveils a newly-researched Montreal ghost story on the 13th of every month!

This service is free and you can sign up to our mailing list (top, right-hand corner for desktops and at the bottom for mobile devices) if you wish to receive it every month on the 13th!

We are also pleased to announce that all of our award-winning ghost tours and haunted experiences are operating and tickets are on sale! These include Haunted Mountain, Haunted Griffintown, Haunted Downtown, the Haunted Pub Crawl and our new Paranormal Investigation into the old Saint-Antoine Cemetery.

Our October blog examines a dark chapter in Montreal’s History when grave-robbing and body-snatching were rampant, leading to numerous sickening scandals and resultant haunted tales. Indeed, Montreal’s most infamous ghost story of the 1800s, that of Simon McTavish’s tobogganing ghost, is partially based on the antics of Montreal’s body snatchers.

Haunted Research

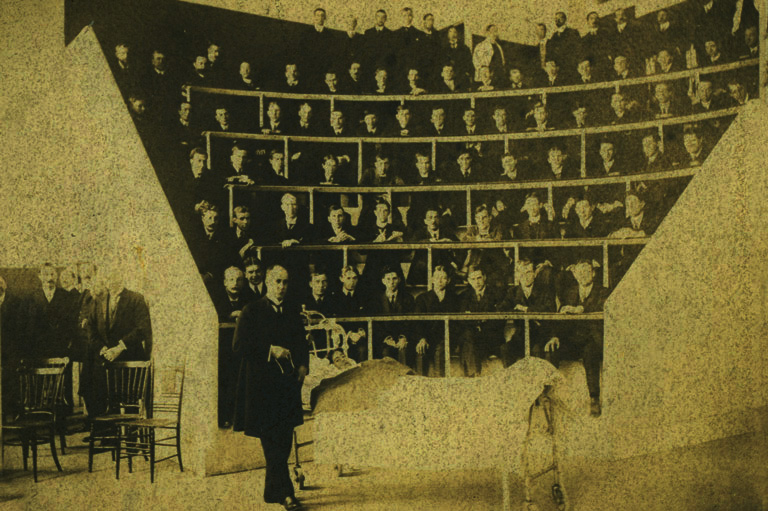

During most of the 1800s, Montreal had a serious problem with body-snatching. With the founding of McGill University in 1821, the Department of Medicine required corpses for education in the Anatomy classroom. Unfortunately, at the time it was illegal to carry out human dissections unless it was part of a criminal’s punishment. Indeed, for the worst criminals, this ultimate and shameful punishment was sometimes written into sentences delivered by local judges.

For example, a lowly tavern-keeper named Charles Gagnon was sentenced to hang following the brutal murder of a client named Joseph Veau dit Jeanveau on Christmas Day, 1832. After being hanged at the old Montreal Gaol and his body collected by McGill University medical staff, the Montreal Gazette observed that it was “the final completion of the awful sentence that consigns the body of the murderer to the knife of the anatomist.”

Interestingly, in this case, the friends of Charles Gagnon hid in the McGill University Medical Faculty before his body arrived, and later stole the corpse, bringing it back to the St. Laurent Parish in today’s Laval where they begged the priest to bury him in consecrated ground. According to the newspaper: “The Curé of that Parish refused sepulture and gave information to the Professors of the College, who have had the body removed to the dissecting room.” Given a major shortage of legal corpses to autopsy in Montreal, the professors were very relieved that their macabre treasure, Gagon’s cadaver, was returned to the Anatomy Theatre.

Because it was rare to receive executed criminals, professors and students had to get creative in their constant quest for fresh corpses to dissect as part of the medical education offered at McGill University. The only realistic solution was grave robbery, or body snatching.

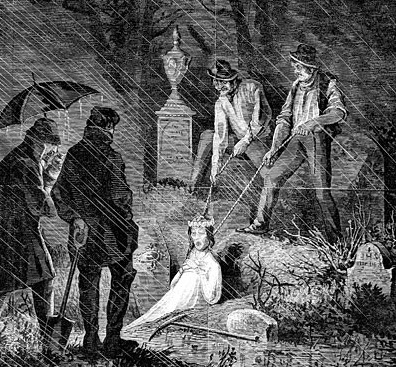

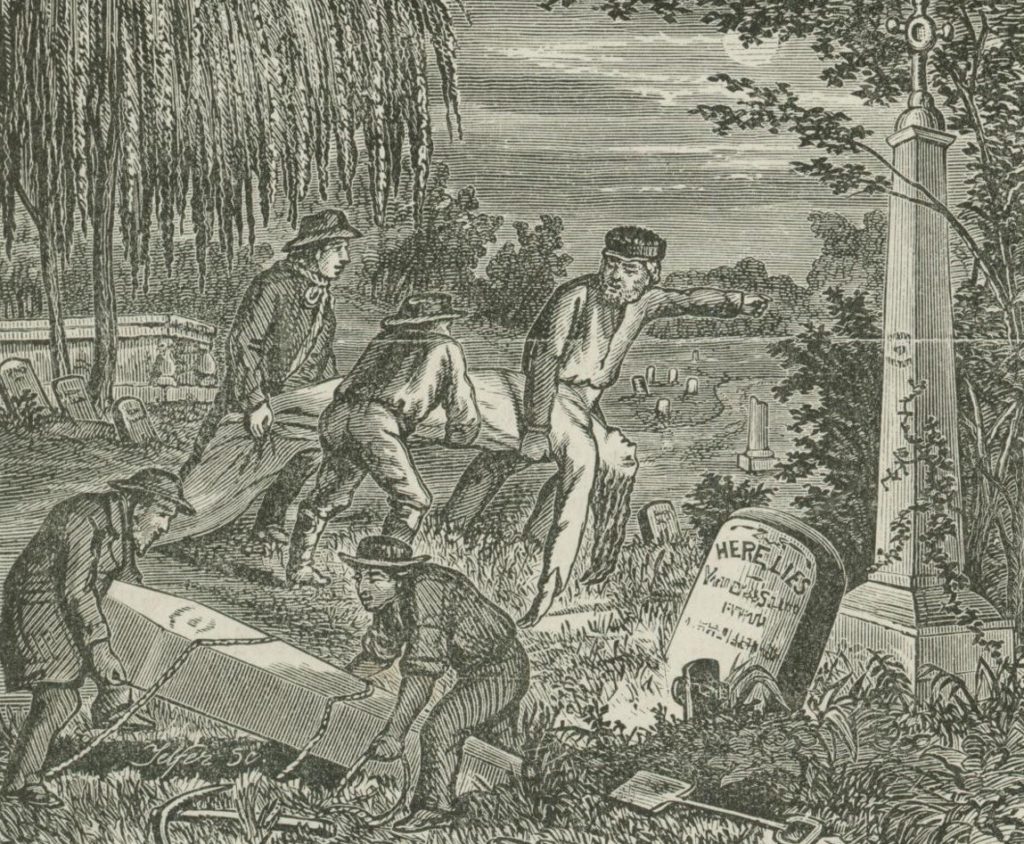

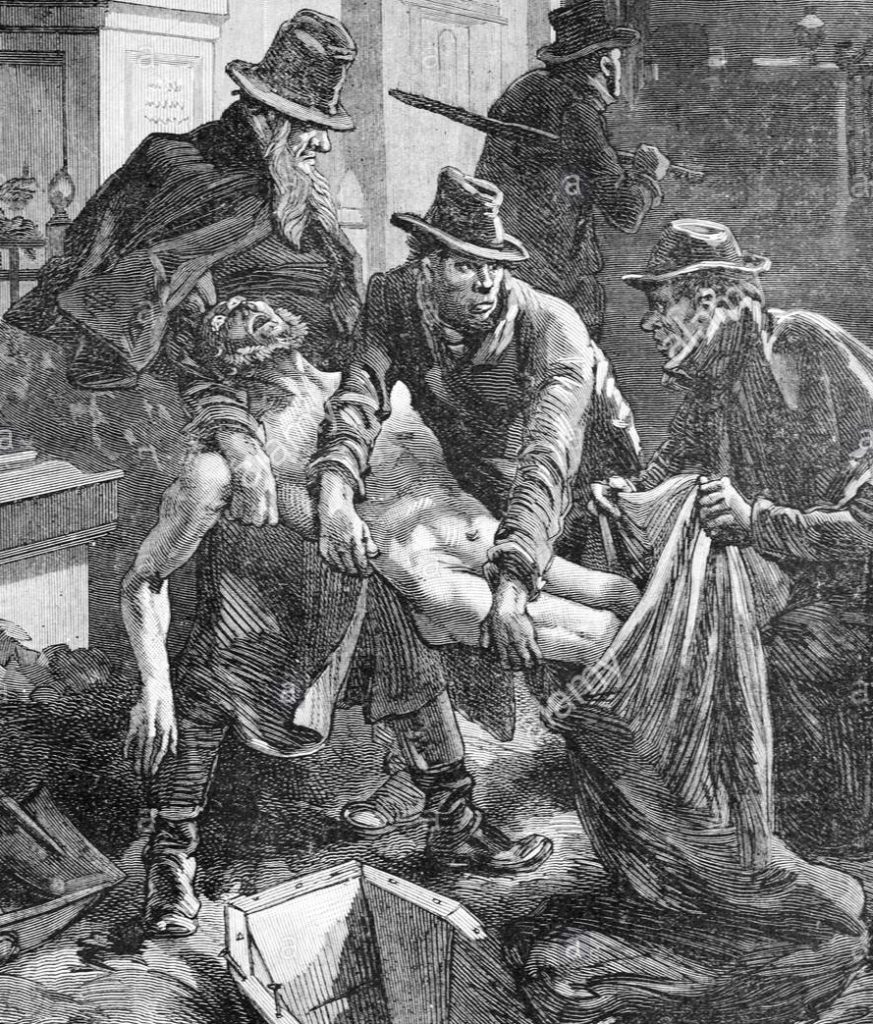

Medical students robbed graveyards and dead houses of their sepulchral possessions and smuggled them back to the university. With a surreptitious wink to the night watchman, the body was dragged into the Anatomy Theatre. In the early days, these “Resurrectionists”, or “Sack-em-up-men”, were a very clever bunch.

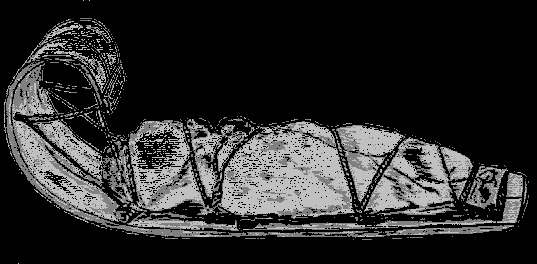

The corpses were exhumed by night and quickly stripped of their clothing and any jewelry to avoid any formal charges of robbery (the corpse itself was not legally designated as private property). Once stripped down naked, the cadaver was swiftly whisked away to the dissecting room.

One of the first bodysnatching episodes that triggered civic unrest among Montreal’s elite happened in the town of Chambly in 1843. The grave robbers burgled the corpse of a well-respected sergeant of the Eighty-Fifth Regiment and left his coffin and clothes strewn among the tombstones. It was an extremely scandalous affair. The police were summoned and soon traced the medical students to an old seigneury house only to find the militiaman’s corpse already dissected and disposed of in a storage vault.

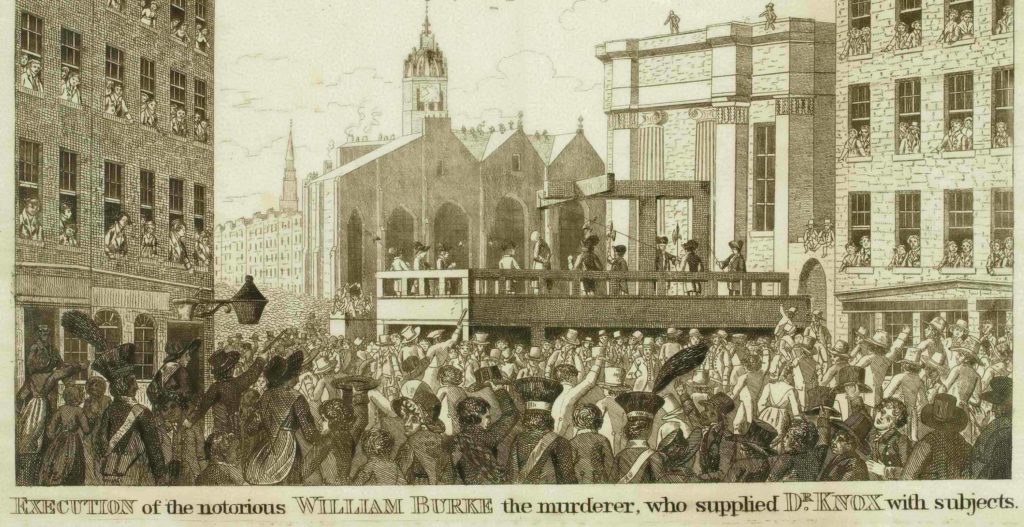

The Montreal Transcript was outraged and denounced the students, describing their dissection room as “A Burking House”. Montrealers were familiar with the twisted legacy of William Burke, a Scottish criminal who murdered people in Edinburgh, Scotland during the 1820s so he could sell their bodies to medical schools. Edinburgh police eventually caught Burke and he was sentenced to hang and then be dissected in public.

Recalling the militiaman’s sacrifices for the British Empire and his many military honours, the Montreal Transcript concluded that “the least the soldier could expect… is that, when consigned to his grave, his remains should lie honoured and undisturbed.”

The scandal so shook the society, that the government took action and unanimously passed the Act to Regulate and Facilitate the Study of Anatomy in December 1843. It proclaimed that the body of any person who died in the care of a government-funded institution was to be handed over to the medical schools unless the corpse was claimed within forty-eight hours, by a “bona fide friend or relative.” Essentially, the law meant that those receiving charity, such as the destitute, the insane, convicts, and children who died in orphanages, would be given over to science unless the body was claimed.

Unfortunately, despite the law, there was still a shortage of bodies to autopsy and grave robbery continued unabated. The fact was that the body snatchers could earn a substantial amount of money per corpse. Many students paid their way through college in this manner, and were absolutely thrilled when Mount Royal Cemetery opened in 1852, followed by the Catholic Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery two years later. Not only were these burial plots secluded among the canopy of the mountain, but they weren’t too far a distance from the McGill Medical Building. Furthermore, from the cemeteries it is was all downhill to the campus, making body snatching easier than ever in Montreal.

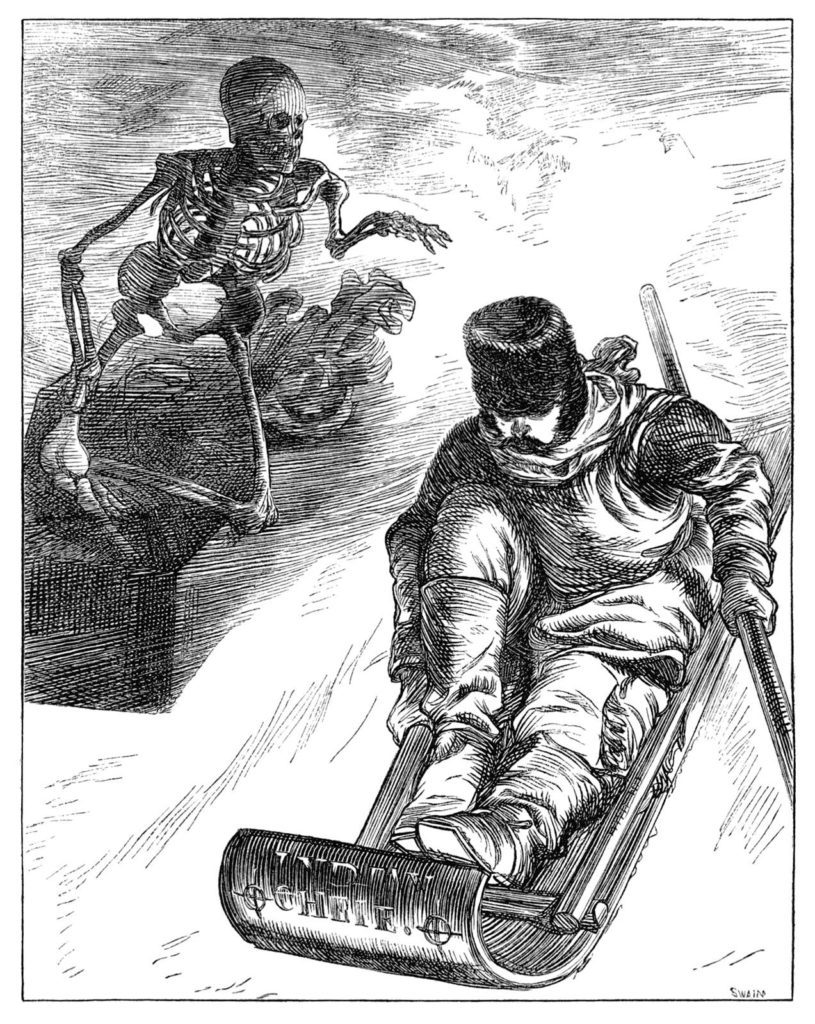

Body-snatching was often a winter activity, due to the frozen ground preventing the burial of bodies. Until the ground thawed, corpses were stored above ground in cemetery “dead houses,” an easy target for students to forcibly enter and steal bodies. A winter body-snatching trip would typically include hiking to Côte-des-Neiges or Mount Royal cemetery in the dark of night, breaking in to a “dead house”, removing the corpses from their caskets, and then tobogganing the bodies down the snow-covered slope.

One professor named Dr. Shepherd recalled that students burgling the cemeteries of Mount Royal would wrap the bodies in blankets and toboggan them down slopes of Côte des Neiges Road.

Occasionally, there would be an incident in which the body would tumble out into the street in full view of passersby. To avoid suspicion, students would explain that there had been a fatal tobogganing accident, resulting in a naked corpse being sprawled across the snowy road.

In 1858, scandal struck again when the corpse of a widow of a high-ranking soldier named Captain Spillen was stolen from the dead house of the Montreal General Hospital.

The body had been claimed in the proper fashion, however when the funeral party opened the coffin for display, they found two sizeable maple logs instead of the widow’s corpse. The Montreal Herald reported: “A shroud was nicely adjusted over the logs of wood, and on the end of them was placed, with cruel ingenuity, the cap of the deceased lady.”

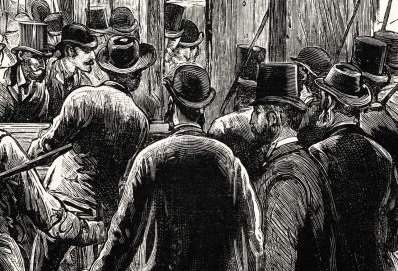

Following publication, a seething, angry mob gathered and began scouring the city for the perpetrators.

Terrified, the body snatchers dumped the naked corpse of Widow Spillen into an empty lot on the corner of Sainte Catherine and Guy streets and then fled as fast as their feet could take them.

Perhaps even more outrageous was a situation recorded in McGill medical student Griffith Evan’s 1862 journal. A group of students had snatched a corpse from a country graveyard only to be betrayed by their sleigh man when the bereaved family announced a reward for the body’s recovery. When the corpse was found at McGill, a humbled Board of Governors returned it to the family, making great public assurances that from now on they “would not admit any corpse into the dissecting room except through the regular channel.”

However, this was an empty promise. Evans explained: “The ‘regular channel’ is from the United States where plenty of negroes are obtained cheap, packed in crates and passed over the border as provisions of flour.” Evans even added that it was somewhat rare for him to ever dissect a white body during his studies at McGill.

In another misadventure, Evans reported that one day deep in the winter of 1862 he was preparing to dissect a human corpse when the calm of the McGill Anatomy Theatre was suddenly broken. Two students, who had illegally stolen a corpse from some unnamed cemetery, were dragging it in for an autopsy when another student burst in, out of breath. He declared: “Good God! That is my aunt; my cousin, her son, is down below at the chemical lecture and will be up here soon.” With this, the anguished nephew fainted and those in the dissection rooms fell into a panic. “What shall we do?” one of them asked.

Another replied: “Dissect the skin off the face quickly!” As the nephew was being revived, the two students grabbed their instruments and immediately set about surgically removing the dead woman’s face, which was soon completely unrecognizable.

When the bereaved son finally arrived, according to Evans: “He went to see the new white subject, cheerfully joked with the dissectors, congratulated them for their successful adventure,” and then set about unwittingly dissecting his own mother.

That same year, a publication called Once a Week, printed by Bradbury & Evans in London, England, published a story called “Nips Daimon” in Volume 6 (December 1861 – June 1862). The deranged tale about a horrible apparition that toboggans down the mountain in a coffin is clearly inspired by the Simon McTavish ghost story. Following the untimely death of the Scottish fur baron in 1804, his ghost was said to terrorize citizens out snowshoeing or tobogganing on the mountain.

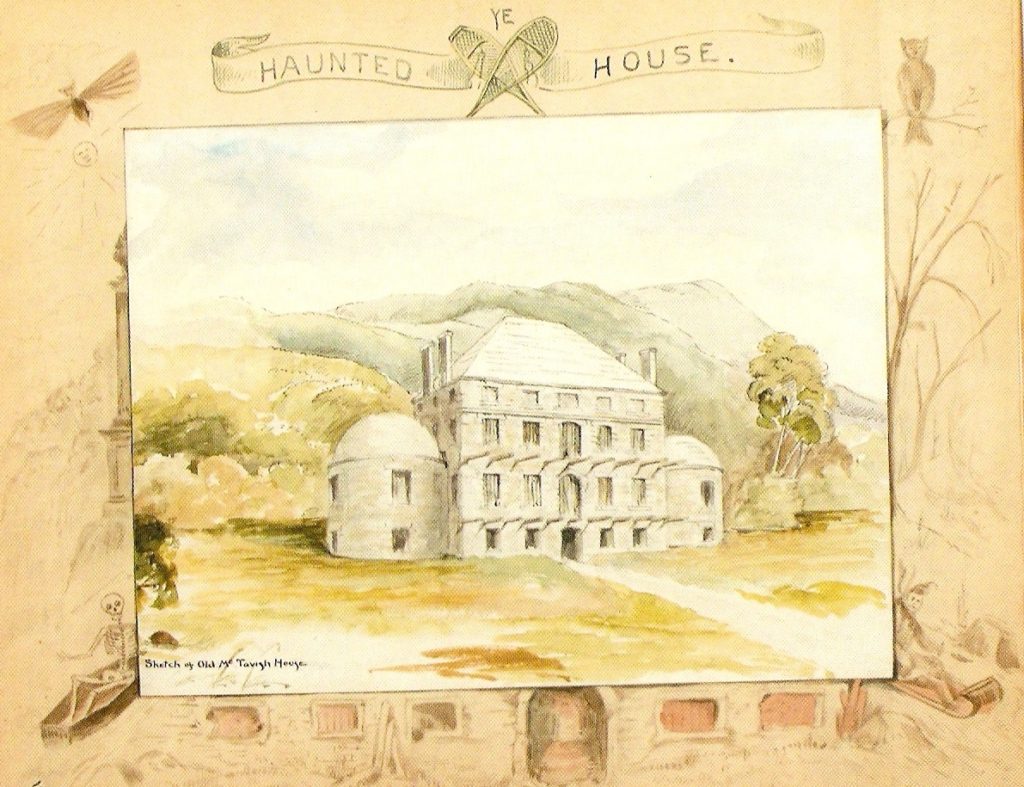

The story was made spookier by the fact McTavish had left an abandoned castle on the slopes above McGill Campus. Over time, the castle began to take on a look of dilapidation, as it slowly decayed and crumbled. Cattle wandered inside the ruin during the summer, and in the winter it took on an eerie appearance, as snow drifted through it. It was grey, gloomy, and almost skull-like, its empty windows staring down at the city below.

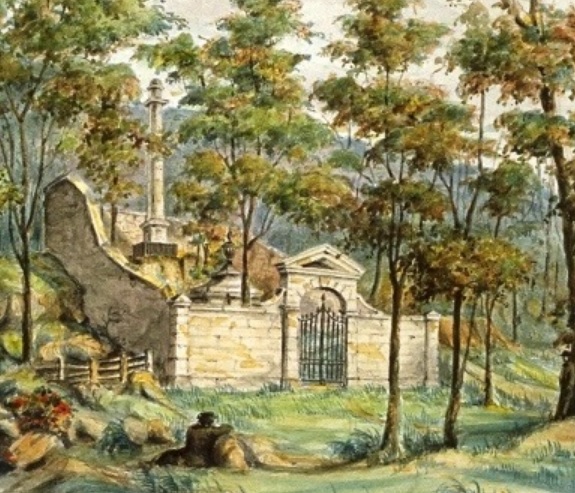

Further up the slope was a mausoleum that housed McTavish’s mortal remains.

McGill University was founded in 1821 and it is said that McGill students would go to burial vault in the winter, wearing snowshoes, and shout and holler to try and raise the ghost of McTavish. In 1827 the students went too far – the locks of the vault were smashed, and the interior of the tomb was violated.

An indignant article appeared in The Gazette condemning the vandalism. The locksmith later reported that he felt a frightening presence in the vault and noticed McTavish’s coffin had fallen on the floor, spilling its contents. Without venturing inside, he quickly repaired the lock and fled.

It didn’t take long before the castle was said to be haunted. Some people reported spirits flitting in and out of the doors and windows and horrible groaning noises coming from within the unfinished building, whereas others said that a ghost could be seen dancing on the roof. Even more strangely, it was said that McTavish could be seen on certain nights tobogganing down Mount Royal – not on a sled, but rather in his own coffin!

While many Montrealers believed the tales and stopped doing winter activities on the slopes, skeptics at the time claimed that it was probably just the Resurrectionists tobogganing corpses down from the cemeteries on Mount Royal to the McGill Medical Building – and not the ghost of McTavish. Whatever the case, the story fired up the imaginations in London. To read “Nips Daimon“, please see pages 602 – 608.

In 1861, the City of Montreal buried the McTavish ghost story, both figuratively and quite literally, by demolishing his crumbling castle and, using the rubble, to literally bury his mausoleum to protect it from further grave-robbery.

As the years passed, body snatching continued abated.

Perhaps the most notorious case occurred in February, 1871, when two deceased Roman Catholic nuns were stolen from the dead house of a church in Lachine. The public exploded in fury, with the Montreal Gazette declaring “there has never yet been related a case of this kind of a more repulsive nature.” Priests thundered from the pulpits, citizens wrote outraged letters to the editor, and a large reward was offered for the return of the sacred bodies.

Perhaps afraid at the outrage they had generated, the thieves panicked and hid the bodies in a snowbank. They then concocted a ploy whereby they would claim the award anonymously in return for the location of the now-frozen corpses. The church complied, and the public outrage only worsened.

The English newspapers described them as “ruthless,” “heartless,” “ghoulish robbers,” “consummate scoundrels,” and “band of half-drunken and blasphemous students” whose “disgusting transactions” amounted to “atrocity” and “diabolical sacrilege.”

One anonymous citizen even published a vengeful warning in the Montreal Star, entitled “Body Snatchers Beware”, on February 11, 1871:

“We saw to-day a tremendous weapon just finished for the watchman at the Côte des Neiges Cemetery. The fun is of enormous proportions and will be loaded with about eight ounces of buck-shot. Parties meditating a raid on the above place of burial will do well to recollect the formidable shooting iron now in the hands of the wide-awake watchman. A pot shot gang of grave desecrators would most likely supply the dissecting room with enough subjects for several weeks.”

The reputation of medical students continued to sink. The Montreal Gazette even alleged that the Resurrectionists were capable of cold-blooded murder and infanticide, making them only more notorious and despised as the century wore on.

!n 1889, a citizen named R.S. Wright, who had graduated from McGill, wrote a letter The Daily Witness entitled “A Mockery of Death”. Wright complained about students from McGill and Laval universities parading human remains through the streets during a Carnival.

Wright recalled his days living in a residence at McGill, describing the medical students as such: “Among them was a clique, or gang, who used to flourish human bones, and talk of making tobacco pouches out of human hide, etc., etc. They were exceedingly drunken and immoral, and I used occasionally to see one of them with his head out of a window vomiting liquor into the quadrangle.”

After this gang threatened to throw Wight’s friend into an “ash pit, under the college, where refuse from dissecting room and other filth were thrown”, he stated: “since that time I have entertained a very poor opinion of men who flourished bones and skulls, or wore slippers made of human hide.”

Wright continued: “None but savages would make a mockery of human remains, or exhibit them in a pantomime.” He then pointed out that First Nations “generally show extraordinary care for human remains, and expend the most tedious ceremonies over them, and when a spot has been consecrated by funeral rites, severe punishment will overtake those who violate it.”

It soon appeared as though things were getting out of control. Illustrious Montreal anatomist Francis Shepherd recalled in the early 1880s, the McGill Faculty of Medicine was paying body snatchers between “thirty to fifty dollars” per corpse, a substantial amount at the time. Indeed, from December 1882 to March 1883 there were a reported 26 episodes of grave robbery in Montreal, prompting demands for stronger legislation.

In 1883, the Anatomy Act of Quebec was passed on March 30. The act effectively served to reinforce and empower the 1843 legislation with coercion and punishment. All hospitals, orphanages, prisons, poorhouses and other government-funded charities were forced to hand over corpses of those who had died there, and the body reclamation period was reduced to 24 hours. Medical schools that acquired bodies from anyone but the municipal Anatomy Inspector would be fined as much as $200, as would government-funded charities that refused to hand over their unclaimed dead. While St. Patrick’s Orphan Asylum initially objected, the government coerced them into sending the dead bodies of orphaned children to Anatomy under threat of punishment.

The Quebec Anatomy Act was an undeniable success. In March, 1884, the Canada Medical and Surgical Journal announced that no grave robbing had been reported in Quebec that winter, stating: “The requirements of the Medical Schools have been amply met.”

And thus, the dark and deranged arts of bodysnatching came to a crashing conclusion. Montreal’s era of grave robbery was effectively over and the twisted exploits of the Resurrectionists began to fade from the public memory. By the twentieth century, any mention of body-snatching had all but disappeared. Yet, as noted in the early issues of The McGill Daily, the legacy of these “brave resurrectionists” lived on in the medical faculty for decades.

Every year, students would celebrate “King Cook”, the medical faculty’s custodian who assisted students in sneaking stolen corpses onto the campus.

These celebrations consisted of a parade down Saint Catherine Street and humorous theatrical productions, which the famed professor Stephen Leacock was known to particularly enjoy.

The notorious “King Cook Celebration” last occurred in 1926, and since then the history of the medical student body-snatching has been largely forgotten.

However, these dark and twisted stories never totally disappeared from the imaginations of Montrealers. Indeed, they have been making a comeback ever since Haunted Montreal started resurrecting the McTavish story by doing in-depth research and offering ghost tours to his gravesite, starting in 2011 with the Haunted Mountain Ghost Walk. Haunted Montreal wants to ensure this deranged part of the city’s medical history and heritage is never, ever forgotten!

Company News

Haunted Montreal is ready for the Hallowe’en Season, with five different ghostly experiences available in both English and French! These include Haunted Mountain, Haunted Griffintown, Haunted Downtown, the Haunted Pub Crawl and our new Paranormal Investigation into the old Saint-Antoine Cemetery. Tickets are now on sale!

Haunted Montreal has also launched our first promotional video ever! Please share it if you like it!

Our new Paranormal Investigation of the Old Saint-Antoine Cholera Cemetery is an experience designed for those interested in the paranormal and ghost hunting, as seen on ghost hunting programs like Rencontres Paranormales, Most Haunted, TAPS’ Ghost Hunters, Haunted Collector and others.

Hosted by an expert in the paranormal, clients will be provided with ghost-hunting tools such as dowsing rods, EMF Readers, Temperatures Guns and other devices to communicate with the many deranged spirits that haunt the Old Saint-Antoine Cholera Cemetery.

The Paranormal Investigation runs every Friday night at 8 p.m. until early November and tickets are now on sale!

Haunted Montreal would also like to announce that our company supports the Victims and Survivors of the Allan Memorial Institute, the only Canadian ghost story with over 300 human victims.

On Sunday, October 6 Haunted Montreal was represented at a protest in Ottawa and plans to continue working with the survivors as they demand justice through a class-action lawsuit:

“The Montreal Experiments consisted of extreme mind-control brainwashing experimentation on unwitting patients, making a mockery of the doctor-patient relationship. Simply put, the Montreal Experiments were a form of psychological torture inflicted upon hundreds of unsuspecting persons and which had traumatizing, damaging, and emotionally-crippling effects that lasted for the remainder of their lives and the lives of their families. To this day, neither the Canadian government, the CIA, McGill, nor the Royal Victoria Hospital have issued formal apologies for their involvement with the Montreal Experiments.”

We will keep our readers updated regarding ways to help support this important case.

Haunted Montreal would like to thank all of our clients who attended a ghost walk, haunted pub crawl or paranormal investigation during the 2019 season! If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page, something that helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours. Lastly, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list.

Coming up on November 13: Lachine Canal

The Lachine Canal is widely considered one of Montreal’s most haunted places. Since it opened in 1825, hundreds of people have drowned in its dark waters. These included suicides, murder victims, people who drowned while swimming and those who died during industrial accidents. The polluted banks are also peppered with old buildings, many being re-purposed into condominiums, that are reputed to be haunted. Last but not least, not only are ghost ships known to ply the canal, but there are also hundreds of bodies buried along its length, mostly victims of the Irish Famine of 1847, resulting in all sorts of ghosts and paranormal activity.

Donovan King is a postcolonial historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbott College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec).

Comments (0)