This month we provide an update on the Hôpital de la Miséricorde and analyze controversial plans by Hydro-Québec to integrate an electricity substation into the haunted site. The ghost-ridden Hôpital de la Miséricorde has been empty for years and is starting to crumble. Located on prime real estate in Downtown Montreal...

Welcome to the forty-fourth installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog!

With over 250 documented ghost stories, Montreal is easily the most haunted city in Canada, if not all of North America. Haunted Montreal is dedicated to researching these paranormal tales, and the Haunted Montreal Blog unveils a newly-researched Montreal ghost story on the 13th of every month! This service is free and you can sign up to our mailing list (top, right-hand corner) if you wish to receive it every month on the 13th!

We are also pleased to announce that all of our ghost tours are now operating and tickets are on sale! These include Haunted Mountain, Haunted Griffintown, Haunted Downtown and the new Haunted Pub Crawl!

Our April blog explores the Dawson Site, an archaeological dig in 1859 by McGill geologist William Dawson that revealed the remnants of an ancient Indigenous city, including burial grounds. To this day, road workers discover evidence of this mysterious and ancestral place when digging in the downtown area south of McGill University, leading many who are in the know to speculate that the area is haunted by its troubled past.

Haunted Research

For those familiar with horror novels and movies, there is a common trope that it is never a good idea to build upon ancient Indigenous burial grounds. Unfortunately for the City of Montreal, a large section of its Downtown core exists on the site of a former Indigenous city and cemetery, resulting in all sorts of speculation that the modern city is haunted.

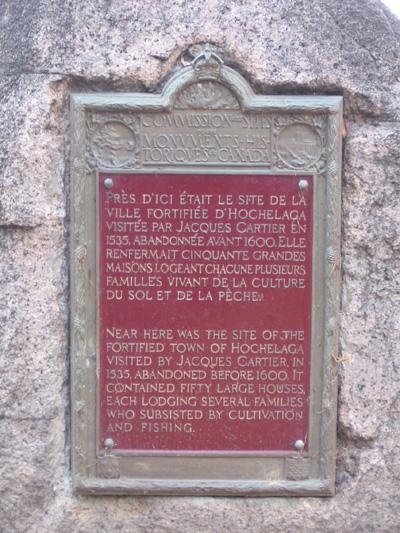

Furthermore, since remnants of the Indigenous city were unearthed in 1859 on the corner of today’s Metcalfe and de Maisonneuve streets, a debate has raged on among scholars of European ancestry about whether or not it is the site of the fabled lost city of “Hochelaga” visited by French explorer Jacques Cartier in 1535.

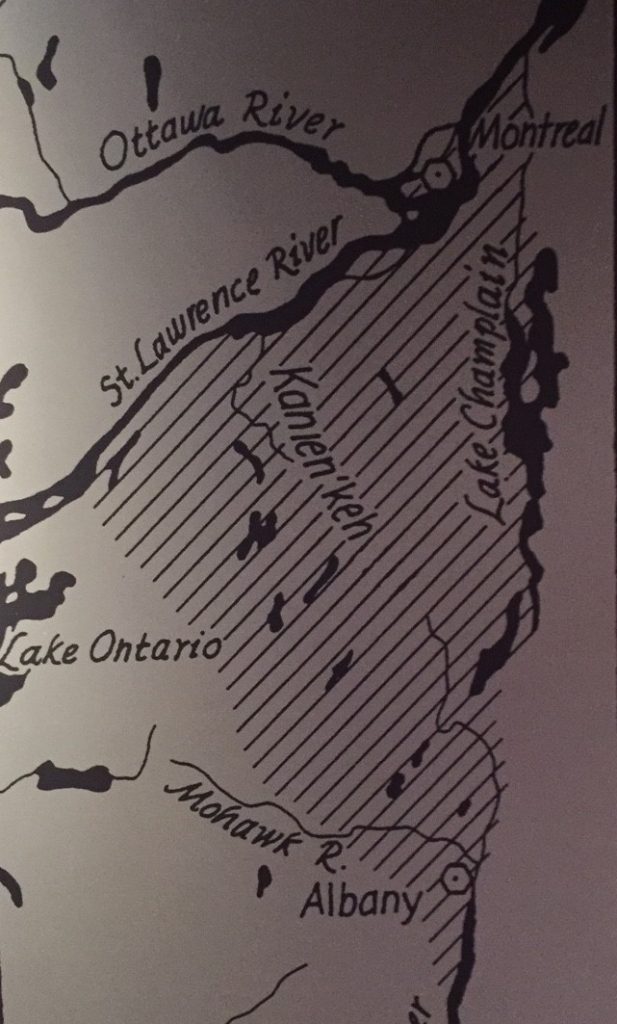

While white historians and archaeologists have long argued about the meaning and significance of this lost, invisible city, Indigenous Elders and historians from the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) First Nation have a much clearer picture. Their understanding of the remnants of the ancient civilization that lurks just beneath Downtown Montreal is based on thousands of years of history in their ancestral territory of Tio’tia:ke, after all.

European-ancestry scholars have long been known to obsess over historical records about Jacques Cartier’s visit as the starting point in their research.

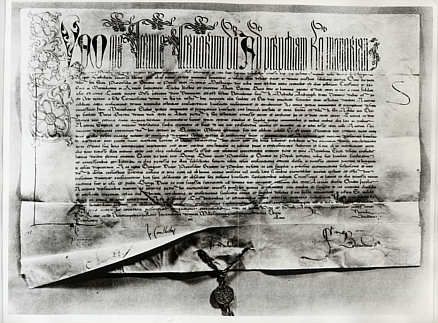

Jacques Cartier’s description of his visit to the island is documented in the wordily titled Brief recit & fuccincte narration, de la nauigation faicte es yiles de Canada, Hochelage & Saguenay & autres, auec particulieres meurs, langaige, & cerimonies des habitans d’icelles: fort delectable â veoir (loosely translated as Short and succinct narrative of navigation to the islands of Canada, Hochelaga & Saguenay & others, including particular customs, languages & ceremonies of the islanders: very delightful to see).

In the text, Cartier documents his visit to today’s Montreal Island. Cartier was exploring the Kaniatarowanenneh (“St. Lawrence”) River and arrived on the island on October 2, 1535. Cartier writes of an Indigenous city, which he calls “Hochelaga,” with thousands of residents, surrounded by expansive cornfields at the base of a large mountain. The fortified city contained at least fifty bark-covered longhouses and was surrounded by three rows of wooden palisades.

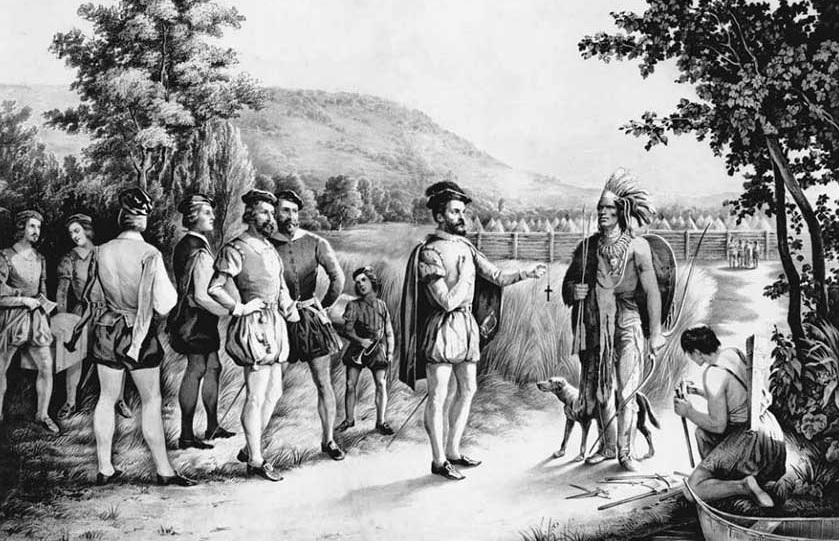

Cartier and his men were met by the city’s residents at a fire near the wood’s edge where they exchanged gifts, before proceeding to a welcome ceremony inside the city itself.

During the welcome ceremony, Cartier was introduced to the chief of the Indigenous city. Cartier handed out gifts of axes, knives, rings, and rosaries to the city’s inhabitants, while they offered the Europeans fish, soup, beans, corn bread, and, during the ceremony, tobacco. Cartier’s logbook, likely written by a companion rather than Cartier himself, describes this encounter as such:

“During this interval, we came across on the way many of the people of the country, who brought us fish and other provisions, at the same time dancing and showing great joy at our coming. And in order to win and keep their friendship, the Captain [Cartier] made them a present of some knives, beads, and other small trifles, whereat they were greatly pleased. And on reaching Hochelaga, there came to meet us more than a thousand persons, men, women, and children, who gave us as good a welcome as ever father gave to his son, making great signs of joy…”

The following day, Cartier was provided with local guides and ascended the mountain, which he labelled “Mount Royal” in honour of his patron, French King Francois I. Cartier never bothered to ask the local inhabitants what the real name of the mountain was (Otsirà:ke), or if he did, it was never recorded.

After his brief visit, lasting a little over a day, Cartier and his men began the journey back up river on October 4th, worried about the upcoming winter.

Cartier’s visit to “Hochelaga” is seen as important to the establishment of settler colonialism in what is now called Canada. It is important to recognize that the widespread acknowledgement of the existence of “Hochelaga” is based on Cartier’s journals. Because his logbooks adhere to settler society’s methods of recording history and because he is a celebrated figure in Western history, Cartier’s account of “Hochelaga” is generally accepted to be reliable by Settler-ancestry scholars. Meanwhile, Indigenous histories not recorded by settlers have often been dismissed by Euro-centric thinkers as unverifiable.

In addition, the account must be questioned because Jacques Cartier was also notoriously dishonest. He told one of his most infamous lies to the residents of Stadacona (today’s Quebec City). In May of 1536, he kidnapped six Indigenous residents, including the city’s leader, and brought them to France, where they all died.

When he returned to Stadacona, he explained that all of his victims were successfully thriving in France, when in fact they had died. If Cartier would tell such dastardly lies to Indigenous people, it is quite likely he would also do so in the writings about his voyage.

Furthermore, Euro-centric reports of this type were often exaggerated as a means to impress Royalty in order to secure funding and resources for future expeditions and many early accounts of “Hochelaga” are adulterated by colonial fantasies

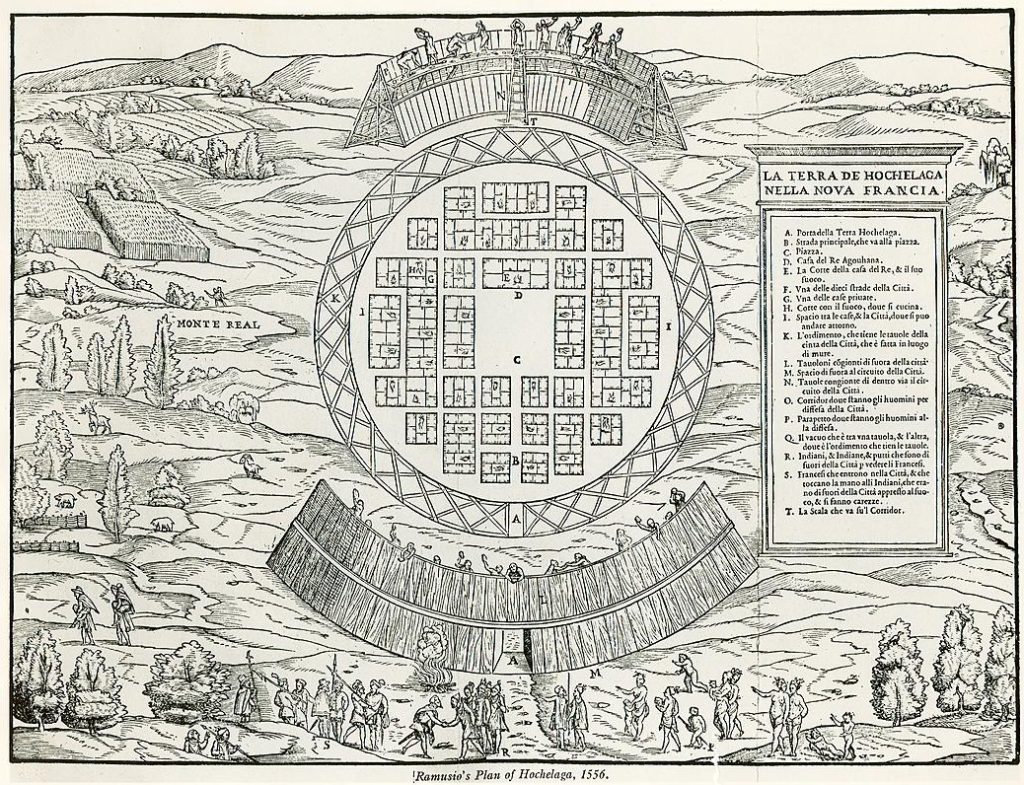

For example, a map of “Hochelaga” was drawn a few years later by Giacomo Gastaldi and printed in the work of the Venetian Battista Ramusio, titled Delle Navigationi and viaggi (Of Navigation and Travel).

The map looks nothing like a traditional Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) city and is modelled on European cities, such as the presence of a central square place and the symmetrical layout of the houses. The map reflects the European perspective on urban planning during the Italian Renaissance and is yet another example of early colonial misrepresentation.

In any case, when the French returned to the island some years later, the Indigenous city Cartier had called “Hochelaga” was no longer there. According to Mohawk Elders, the city’s residents had retreated south to the Mohawk Valley to reorganize due to epidemic diseases and warfare brought on by French colonization.

In 1642, “The Society of Notre-Dame of Montreal for the Conversion of Savages of New France” founded the French colony of Ville-Marie on the island, despite warnings from the governor in Quebec City that it was “Iroquois” (Kanien’kehá:ka) territory. In response, the leader, Sieur de Maisonneuve, stated: “It is an honour to accomplish my mission; even if all the trees of the island of Montreal should change into as many Iroquois.”

Needless to say, the following year when the Kanien’kehá:ka First Nation learned that their territory had been colonized by Europeans, a brutal and lengthy war erupted. When the French colonists began to lose, the Carignan-Salières Regiment was brought in from France to launch genocidal scorched earth campaigns whereby they located and burned down several Kanien’kehá:ka villages. The brutal war lasted, on and off, until 1701, when the Great Peace of Montreal was signed.

With peace secured, the colony of Ville-Marie was able to continue growing on un-ceded Kanien’kehá:ka territory. When the British took over the city in 1760, they chose “Montreal” as its official name.

Under the British Regime, the French colony was transformed into a booming city, business hub and financial center. It began to expand very quickly.

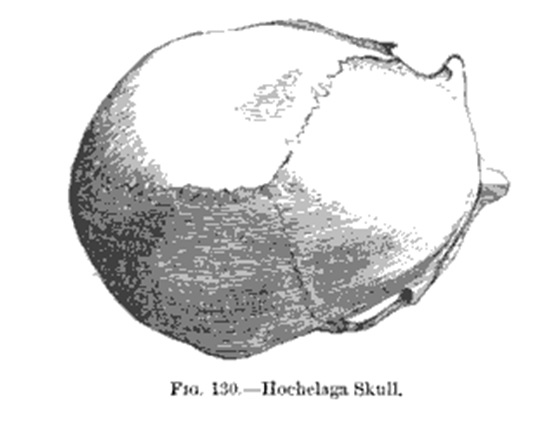

In 1859, construction workers began building houses in a sandy area on the corner of Metcalfe and Burnside (today’s de Maisonneuve) Streets. As they worked, they began unearthing remnants of skeletons, fire pits, tools, pottery, longhouse posts, and other evidence that an Indigenous city was formerly located on the site. One particularly famous artifact is called the “Hochelaga Skull”, an Indigenous cranium that was studied by Euro-centric scientists and reported in books such as Prehistoric Man: Researches Into the Origin of Civilisation in the Old and the New World, Volume 2.

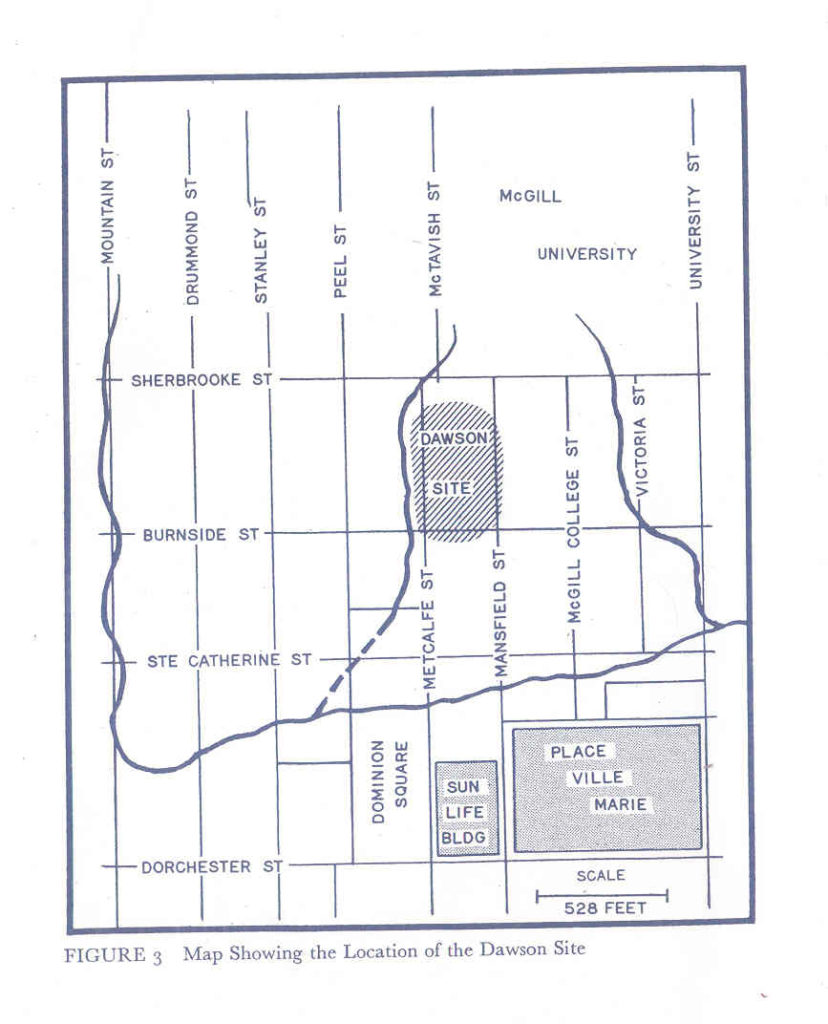

At this time, William Dawson, a scientist and geologist was the director of McGill College. Dawson examined the sandy area, located between Sherbrooke and Burnside (today’s De Maisonneuve) Streets and Metcalfe and Mansfield Streets, and concluded that it once hosted the village of Hochelaga. In 1860, near this same spot, two workers, digging for sand to be used as landfill, uncovered 20 Indigenous skeletons and numerous stunning artefacts from the famous lost city.

Dawson published his findings and many were quick to pronounce his conclusions correct so as to satisfy the intrigue surrounding Hochelaga’s mysterious disappearance. The area has since been known as the “Dawson Site”, Montreal’s first archaeological dig.

In 1920, a commemorative plaque was erected on a boulder christened the Hochelaga Stone near the main entrance of McGill University.

Since those days, Indigenous artifacts have continued to appear during road work. For example, during work from 2016-2017, a discovery was made at Sherbrooke and Peel streets, well outside the area of the original Dawson Site. Archaeologists found thousands of artifacts and evidence of the lost city, including pottery, the tooth of a beluga whale and the grave of young adult.

Based on various archaeological findings, amateur historians Ian Barrett and Robert J. Galbraith believe the lost city “extended at least from University Street on the east to Mount Royal on the north, south to corn fields covering Dominion Square, and west to Fort Street and maybe even beyond.”

However, due to the forces of urbanization that have disturbed so much of the original city’s remnants, nobody really knows how large the lost city lying under Downtown Montreal actually is.

There is another current of thought by white academics that “Hochelaga” was not located where the downtown core exists today. The theory suggests Jacques Cartier went around the other side of the island, thus placing “Hochelaga” anywhere from Outremont to Lafontaine Park to Laval. For the City of Montreal’s 375th anniversary, the Hochelaga Project was launched at the University of Montreal to search for the mystical village.

In addition to the strange idea that the lost city is still undiscovered, despite there being ample evidence is was located where the downtown core is today, another very important point of contention is who the original inhabitants were.

White scholars with European ancestry such as James F. Pendergast, Bruce G. Trigger, and Roland Tremblay have long argued that a distinct group of Indigenous people called the “St. Lawrence Iroquoians” existed in the river valley and then suddenly vanished without explanation.

In 2006, the Pointe-à-Callière Montréal Archaeology and History Complex hosted an exhibition about the “lost” tribe of “St. Lawrence Iroqouians”, complete with pottery shards, dog bones and other artefacts. Based on white scholarship and entitled “The St. Lawrence Iroquoians – Corn People”, the exhibition posited that a the “St. Lawrence Iroquoians” existed on Montreal island at the time of Jacques Cartier’s visit in 1535, but mysteriously disappeared shortly thereafter, at some point before the arrival of Samuel de Champlain in 1603.

Needless to say, historians, Elders and activists of the Kanien’kehá:ka First Nation disagree with this bizarre theory and argue that it was created to justify the colonization of their traditional ancestral territory.

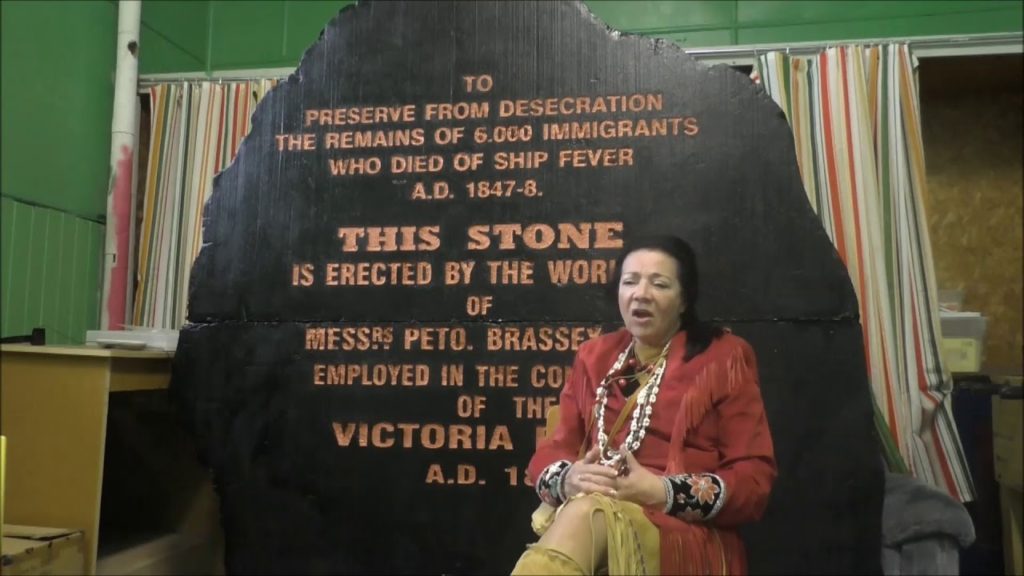

Kahentinetha Horn of Mohawk Nation News decided to visit the “Corn People” exhibition.

In her article “Disappearing Iroquois Myth “Busted””, she wrote:

“At the last minute on Tuesday, November 7, we Iroquois found out there was an exhibit opening at the Calliere Museum in Old Montreal. It was on the “Mysterious Disappearance of the St. Lawrence Valley Iroquois”. They wish! Four of us from Kahnawake, Kanehsatake and Tyendinaga decided to go and look it over. We were curious as to how they got the idea that we had “disappeared” or that there was any mystery to be solved.”

They toured the exhibition and were left feeling offended. Horn wrote:

“We complained to the guide that we had not disappeared, that he was not staring at ghosts, that this whole exhibit was misleading and that we are definitely still here. In other words, we were unconvinced by the story of our death. Excited and anxious, security was summoned. We were followed around for a bit. Then a short little women sergeant appeared and told us that the museum would refund our money.”

In conclusion, Horn suggested:

“We’d prefer they shut down this travesty. Or if the public sees it, they should be told it’s a fictional representation meant to mislead the public and justify colonization.”

There has long been an argument that French settlers were justified in colonizing the Montreal Island because the land was seen as empty. Terra nullius is a Latin expression meaning “nobody’s land”, and European colonizers adhered to this concept, which is to say the ancient and inhabited land was theirs for the taking. Terra nullius is based on 15th century Catholic decrees that formed the European legal basis for colonialism around the planet.

However, Mohawk Elders and historians disagree that Terra nullius is a legitimate concept because their ancestors were never included in discussions about the religious decrees that “legitimated” the occupation and colonization of their ancestral territory. Furthermore, the Eurocentric documents are inherently racist because they position Europeans as superior to all other races to the point of being allowed to colonize their lands.

According to former Kanien’kehá:ka chief Christine Zachary-Deom: “We’ve been located throughout Montreal for centuries, and for actually 10,000 years, and when you walk on the Island of Montreal you’re really walking on Mohawk Nation territory.”

Mohawk academics agree.

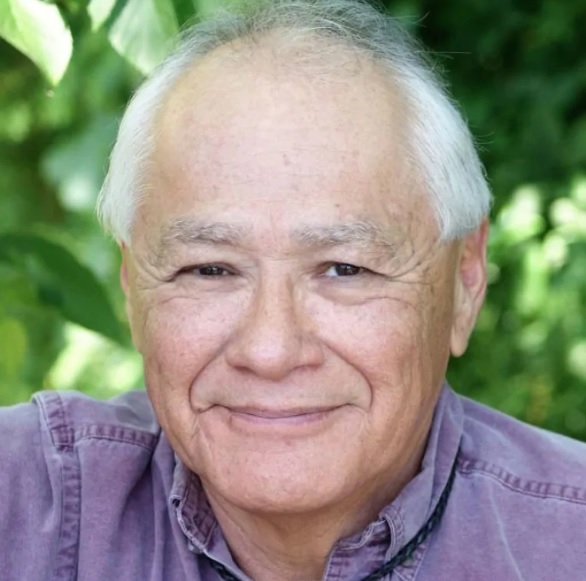

According to Queens University: “Dr. Michael Doxtater is an award-winning documentarian and scholar of international stature. A member of the Haudenosaunee Nation, and fluent in Kanyen’keha (Mohawk), Dr. Doxtater has both a deeply-rooted understanding of traditional oral knowledge.” According to Dr. Michael Doxtater, the name “Hochelaga” is not even correct.

Jacques Cartier had a very high error-rate when attempting to transcribe Indigenous languages and the real name of the Indigenous city he visited, according to Dr. Doxtater, is Hotsirà:ken, which means “place of the fire” and is where the name Hochelaga stems from.

According to Doxtater: “Hotsirà:ken is an ancient ancestral place, an Indigenous place. It was a Mohawk village of around 5,000 people on the island. The island was what I would call a metropolitan trade centre. The Algonquin people would come down the Ottawa River, [people] would come down from the Innu territories up the St. Lawrence and then there would be the various Iroquois linguistic groups that would converge and that was a major, major trade centre.”

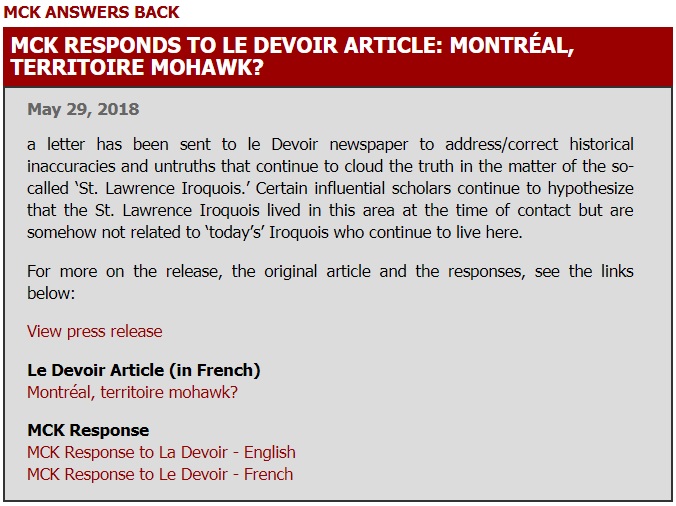

Unfortunately, some European-ancestry historians and journalists are in denial and persist that Tio’tia:ke is not a Mohawk territory. Questionable articles have appeared in French in Le Devoir and La Presse that can only be described as Euro-centric historical revisionism.

To refute these disingenuous and Euro-centric opinions about the ancestral Mohawk territory being empty and therefore ripe for the taking by French colonists in the 1600s, the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke set up an Answer Back web page to set the record straight.

So frustrated is the Mohawk First Nation by this ongoing denial, that Kahnawake Mohawk Kenneth Deer, a representative of the Haudenosaunee External Relations Committee, which represents the Iroquois Confederacy Council on international matters, visited the Vatican with a delegation in 2016. The delegation asked that the Pope rescind the racist doctrine of Terra nullius, explaining in a press release they were seeking revocation of three papal bulls because:

“They were the ‘blueprint’ for conquest of the New World; they provided moral justification for the enslavement and conquest of Indigenous peoples worldwide; they are an ongoing violation of contemporary human rights legislation; and other communities currently struggling to save their lands are threatened by modern-day ideologies of inequality anchored in the papal bulls.”

The leaders of the delegation were determined to tell Pope Francis that it was “time for the Vatican to own up to its responsibility for legitimizing a genocide committed against Indigenous peoples and to show its good faith by revoking three Papal Bulls of Discovery: Dum Diversas (1452), Romanus Pontifex (1455) and Inter Caetera (1493), still in force today.”

While the Pope did meet briefly with Kenneth Deer, all the pontiff could muster up was “I will pray for you,” before giving him a little red box with a set of rosaries.

After meeting with other Vatican officials, Deer said: “The process of working towards the goal of getting rid of the roots of the colonial era has commenced.”

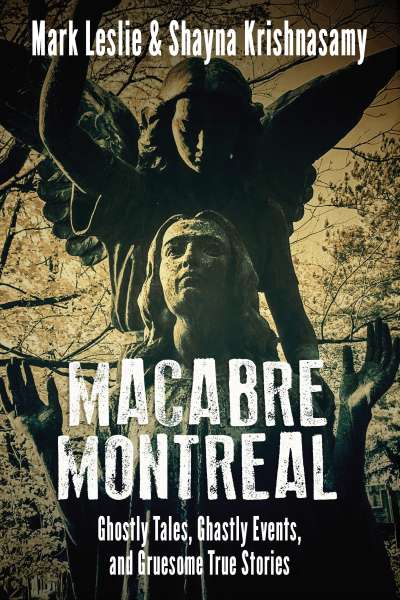

Returning to the lost Indigenous city lurking beneath Downtown Montreal, there are also theories that the site is paranormal. In Macabre Montreal, authors Mark Leslie and Shayna Krishnasamy devote a whole chapter to the Dawson Site called “The Missing Village of Hochelaga” (pages 146 – 148). After examining all the theories put forward by white academics with Euro-centric perspectives, the authors hypothesize that Hochelaga may have never existed at all as a real village. They speculate that it may have been a “ghost village even when Cartier landed there, already long-destroyed, inhabited by spectres so convincingly real that Cartier could not tell the difference.”

“Did explorer feast with the dead on a fateful voyage in 1535?” ask the authors, concluding “we may never truly know.”

To add to the creepy factor, there is a chiselled stone skull that stares down from the façade of the abandoned University Club on Mansfield Street. Its hollow sockets seem to stare directly onto the site of the buried Indigenous city.

The University Club of Montreal was founded in 1906 as a private old boys club for a group of the professional and academic elite. In 1913, the organization had its clubhouse built on Mansfield Street, located on part of the Dawson Site. The gracious limestone and brick building was designed by Percy Erskine Nobbs, an influential architect trained in the Arts and Crafts movement and known for exquisitely crafted buildings designed on an intimate, human scale.

Over the years, the University Club hosted the city’s elite, from business magnates to prime ministers. In 2016, the clubhouse was abandoned and sold because the building required major renovations and the cost of maintaining it was seen as just too high.

One must wonder why the architect included a skull in the façade of such a prestigious club. The most common symbolic use of the skull is as a representation of death, mortality and evil. It is also a symbol of the Illuminati and is used by the infamous Skull and Bones Secret Society at Yale University.

Was architect Percy Erskine Nobbs involved in the Illuminati, or did a higher-up in the University Club request the macabre decoration? Perhaps it was meant to represent the Hochelaga Skull, discovered on the same site?

Whatever the case, it is an ironic symbol that the University Club, a bastion of white privilege and colonialism, features a deranged skull staring down at the invisible Indigenous city lurking below the pavement.

It is an evil reminder of the ravages of colonization, whereby European powers attempted to subjugate or destroy Indigenous civilization through all sorts of means, including cultural genocide. Today, these issues have come to the forefront.

While the colonial governments in Canada and Quebec made several half-hearted attempts to address the extreme damage to Indigenous people caused by colonization in the past, efforts were stepped up after the United Nations launched the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007. The UN recognizes that doctrines such Terra nullius are not legally valid and that the continuation of colonialism is a crime which violates the Charter of the United Nations.

In 2008, Canada created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate Canada’s residential school system, one of its many colonial tools used to commit cultural genocide against Indigenous people. Under the leadership of Senator Murray Sinclair, survivors of the “schools” recounted the horrors they experienced and the extreme damage this forced assimilation policy did to their culture, languages and communities.

In 2015, the Commission released its final report, a detailed account of what happened to Indigenous children who were physically and sexually abused in government boarding schools, where an estimated 3,200 children died from tuberculosis, malnutrition and other diseases resulting from poor living conditions. The Commission published 94 “Calls to Action” urging all levels of government to work together to change policies and programs in a concerted effort to move forward with reconciliation.

There can be no denying that colonization is an ongoing problem in the City of Montreal and indeed, across the Americas. The legacy left by European powers in present-day Canada is a nation that only uses the colonial languages of English and French, at the expense of the original Indigenous tongues. Many of these once vibrant languages are now endangered due to the government’s policies of cultural genocide.

Importantly, 2019 marks the United Nations Year of Indigenous Languages and there is a sense of urgency in that only 3500 people speak Kanien’keha (the Mohawk language) on the planet, versus over 275 million who speak French and 1.5 billion who speak English.

Embarrassingly, officially-licensed City of Montreal tour guides are not even taught how to say “Hello” in Mohawk (“Kwe Kwe”) during their mandatory training at the Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec (ITHQ). Instead of helping revive an endangered Indigenous language and teach tour guides unbiased history, the ITHQ’s curriculum has traditionally been described as “Euro-centric”, leading to poorly-trained tour guides who are ignorant of Indigenous history, languages, protocols and contemporary issues. The same problem exists in the Quebec Education System, resulting in generalized ignorance among the Settler-ancestry population and the blind acceptance of Euro-centric ideology.

Thankfully, there is an Indigenous resurgence and groups such as Idle No More have been actively challenging racism and colonialism in different ways and demanding positive social change. Today, Indigenous voices are being heard more and more often and many media organizations, such as CBC, now offer Indigenous content.

Slowly but surely, various levels of government are starting to listen and take action. According to a survey in 2016, Montreal has approximately 35,000 urban Indigenous citizens and the numbers are growing quickly. Montreal is, without a doubt, the most Indigenous city in Quebec. All eleven First Nations and Inuit peoples in the province are represented, along with many other First Nations and Métis from across North America, or Turtle Island, and beyond.

In 2008, the City of Montreal decided to try and improve conditions for Indigenous citizens, and so began supporting and engaging with RÉSEAU pour la stratégie urbaine de la communauté autochtone de Montréal.

In 2016, the City of Montreal firmly committed to reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples and declared its commitment to becoming a metropolis of reconciliation. This commitment includes the implementation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action and the unanimous endorsement of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, signed by the City on August 21, 2017.

Due to ongoing mis-education by government-sponsored Education and Tourism systems, it can be very challenging for people of Settler ancestry to accept that they have not been taught properly and to try and seek out the Truth, as recommended by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

One good starting point is the Indigenous Ally Toolkit, which states that “Educating yourself is an ongoing process. Change will not be easy and you will never truly be an expert on Indigenous challenges and realities, but you can work in allyship.”

Returning to the lost Indigenous city, in 2017, a movie called Hochelaga, Land of Souls was released. Witten and directed by François Girard , the film connects local histories with contemporary Quebec in a tale of historical fiction. Screened at the Toronto International Film Festival, Hochelaga, Land of Souls won four Canadian Screen Awards and was submitted for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards, demonstrating a strong interest in the history of the Kanien’kehá:ka First Nation.

In conclusion, it is puzzling that some historians and archaeologists of the colonizer society continue to squabble about the presumed location of “Hochelaga” and whether or not the island is un-ceded Mohawk territory.

Mohawk Elders and historians know the truth: Montreal exists on the un-ceded Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) territory of Tio’tia:ke in northern Kanien’keh, also known as the Land of the Flint.

Furthermore, given all the archaeological evidence, it seems fairly obvious that the lost city of Hotsirà:ken lies mere inches below Downtown Montreal.

Whatever the case, there are much larger and more important issues that need to be addressed, including the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and ultimately decolonization. The remnants of the lost Indigenous city will continue to haunt these dialogues, as the truth is revealed, layer by layer, for the colonizer society to reflect on.

Company News

Haunted Montreal is pleased to announce that our public season of ghost tours has begun! These include Haunted Mountain, Haunted Griffintown, Haunted Downtown and the new Haunted Pub Crawl! Tickets are on sale!

Our new Haunted Pub Crawl is led by a professional ghost storyteller and visits three haunted bars. Starting at McKibbin’s Irish Pub in Downtown Montreal on Bishop Street, guests not only learn about many of the haunted drinking establishments in the city, but also hear Montreal’s most infamous ghost stories.

While sipping suds, guests enjoy haunted pubs, spine-tingling Montreal ghost stories and learn about the historical forces that transformed the ancient Indigenous island of Tiotà:ke into Ville-Marie, an austere French colony founded by Catholic evangelists.

After the British invaded, the city became a booming financial center and crime hub, a site of violent rebellion and subversive revolution and finally into Canada’s most haunted city.

Clients hear the paranormal tales behind mysterious McKibbin’s Irish Pub, the famous Sir Winston Churchill, funeral-home-cum-discotheque Club Le Cinq and, of course, Hurley’s Irish Pub, where a ghost known only as the Burning Lady haunts the establishment.

The ghost storyteller regales guests with Montreal’s most deranged and infamous ghost stories, including Simon McTavish, a Scottish fur baron known to toboggan down the slopes of Mount Royal in his own coffin, the ghost of John Easton Mills, Montreal’s Martyr Mayor who perished while tending to typhus-stricken Irish refugees during the Famine of 1847, and Headless Mary, the ghost of a Griffintown prostitute who was decapitated by her best friend in the shantytown in 1879. She returns every 7 years to the corner of William and Murray Streets, still looking for her head!

Join Haunted Montreal on this unforgettable pub crawl, where you can drink some spirits with a spirit, all the while learning about the city’s deranged history and hearing spine-tingling local ghost stories!

For full details, including a description, the starting location and schedule, please visit our new web page! Join us at 3 pm any Sunday of the year for a haunted pub crawl in English or at 4 pm in French! Tickets are now on sale!

Haunted Montreal also offers private tours and pub crawls for company outings, school groups, bachelorette parties and all types of gatherings. Please contact info@hauntedmontreal.com to organize a private tour.

We are also pleased to promote a book called Macabre Montreal.

Written by Mark Leslie and Shayna Krishnasamy, it is a “collection of ghost stories, eerie encounters, and gruesome and ghastly true stories from the second most populous city in Canada.

The authors write:

“Montreal is a city steeped in history and culture, but just beneath the pristine surface of this world-class city lie unsettling stories. Tales shared mostly in whispered tones about eerie phenomena, dark deeds, and disturbing legends that take place in haunted buildings, forgotten graveyards, and haunted pubs. The dark of night reveals a very different city behind its beautiful European-style architecture and cobblestone streets. A city with buried secrets, alleyways that echo with the footsteps of ghostly spectres, memories of ghastly events, and unspeakable criminal acts.”

With the introduction written by Haunted Montreal, Macabre Montreal is a must-read for anyone interested in Montreal’s dark side.

Haunted Montreal would also like to thank all of our clients who attended a ghost walk or haunted pub crawl recently!

If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page, something that helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours. If you have any feedback, please email us at info@hauntedmontreal.com so we can improve our visitor experience.

Lastly, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list on the top right of this page.

Coming up on May 13: The Savannah Ghost

The Savannah Ghost is a personal ghost story. In January of 2018, I visited Savannah, Georgia to research haunted pub crawls in “America’s Most Haunted City”. I booked a room in one of the most haunted lodgings in historic Savannah, the 17Hundred90 Inn, for approximately a week. As I carried out my research, including into the ghosts haunting the 17Hundred90 Inn, I began to feel more and more uneasy. These feelings followed me when I returned to Montreal, and I began to suspect that I had brought something paranormal back with me. This horrifying experience would completely derail my life for several months until an Irish priest, delivering an annual mass on the ruins of St. Anne’s Church in Griffintown, was able to expel whatever it was that was haunting me.

Donovan King is a postcolonial historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbott College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec).

Came across this site accidentally as I was looking for information on the Dawson Tavern which was partly owned by my Dad back in the ‘30’s-40’s.

Fascinating!