High above Montreal’s streetscape, hundreds of gargoyles and grotesques are carved into the architecture of various older buildings and churches. Sculptors created gargoyles to drain water and allegedly to ward off evil spirits, a tradition dating back to mediaeval Europe. Grotesques are similar stone creatures but do not feature any plumbing.

Some legends say that gargoyles can communicate with others when the rain passes through their mouths. Other myths claim that gargoyles and grotesques sometimes come to life at night. Montreal’s gargoyles are shrouded in mystery and a local legend from the late 19th Century highlights one of their deranged antics after sunset.

Welcome to the thirty-third installment of the Haunted Montreal Blog! Released on the 13th of every month, the January 2018 edition focuses on research we are carrying out into La Chasse-galerie, a famous legend from the days of New France. In the story, a group of isolated woodsmen in the Gatineau region make a deal with the Devil one frosty New Year’s Eve. They want to go to a party in Lavatrie, hundreds of kilometers away, so the Devil gives their canoe the power of flight in exchange for a promise. However, trouble begins to brew when they fly over Montreal on the return voyage. With the 2017 Public Season now over, Haunted Montreal is in winter mode and is not offering any more public ghost tours until May, 2018. Stay tuned for some of the ideas we are planning for the winter months!

HAUNTED RESEARCH

With the passing of the New Year, the fantastic legend of La-chasse galerie is still fresh in the minds of many Montrealers, if only for the fact that it is the most famous Québecois story set on New Year’s Eve. According to local lore, those who hear a noise in the sky on New Year’s Eve should look up because they just might spot a canoe flying through the air full of terrified lumberjacks on their unholy journey to Hell.

Legends from the era of New France often involved a “Deal with the Devil.” Indeed, the colonization of present-day Quebec was initially carried out by Jesuit missionaries who practiced a very austere form of Catholicism. Seeing the Devil everywhere in the dark forests of the “New World”, the Jesuits constantly warned the French colonists not to be tempted into sin, lest they compromise their souls. One zealous Jesuit priest named Paul Le Jeune actually went as far as describing New France as the “Empire of Satan,” prompting fertile imaginations to concoct fantastic, magical legends.

With such prominent religious discourse, the Devil features prominently in the French colony’s earliest folklore. The tale of La-chasse galerie is thought to be an inter-cultural story combining European folklore and a First Nations legend about a flying canoe.

Many folklorists believe the story is partly based on a medieval legend called “The Wild Hunt” about a wicked man named Lord Gallery. The Lord hailed from Poitou, France, a settlement where many of the colonists were born. Instead of going to church on Sundays, Lord Gallery preferred to go hunting (la chasse in French), something considered sacrilegious at the time. As punishment, Lord Gallery was sentenced to hunt at night for eternity, all the while being chased by galloping horses and howling wolves.

Thus the title, La-chasse galerie, means Gallery’s Hunt, which signifies the work of the Devil. The essential moral of the story is that those who obey the teachings of the Catholic Church will never be led astray by sin.

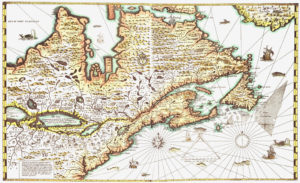

As French colonization began in the early 1600s, it soon became apparent that there were a lot of riches to be made in fur trading. In the 1640s, a class of independent traders began to develop known as the coureurs des bois, or “runners of the woods.” These adventurous merchants adopted customs of the First Nations and learned their languages as their canoes penetrated deep into the continent’s interior in search of commerce.

Needless to say, it is likely the story of La-chasse galerie evolved during their lengthy voyages through the wilderness. With the settlement of Ville-Marie on Montreal Island becoming the center of the fur trade in the late 1600s, it wasn’t long before the astounding legend was being told in the colony.

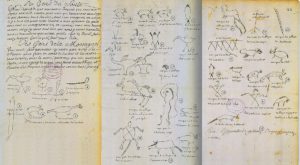

The strange idea of flying canoes certainly gripped the imaginations of the French colonists. In 1661, following a series of earthquakes that shook New France, a Jesuit priest named Paul Le Jeune reported human screams coming from the sky and fiery canoes hurtling through the air above the colony.

He wrote: “The canoes, which appeared all on fire, fluttered through air all around Kebec, were only a light, but true omen of the enemy canoes that prowled our coasts this summer.”

Describing the situation as a “disastrous prognostic”, he theorized that the aerial screams might have been caused by French prisoners-of-war taken during the military conflicts between the colonists and the First Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (what the French called the “Iroquois”). The brutal war was a result of the French attempting to colonize un-ceded First Nations territories and concluded in 1701 with a treaty called The Great Peace of Montreal.

Flying canoes appear in other legends as well. In one Montreal tale retold and published by folklorist S.E. Schlosser, the Devil himself rides a flying canoe with twenty werewolves. In the story entitled “The Devil and the Loup Garou,” a lazy farmer named Jean Dubroise makes a deal with the Devil so he doesn’t have to do any work on his farm. Instead, the Devil orders the werewolves to do it for him. When the local priest finds out and sprinkles holy water on the property, the Devil becomes enraged and whisks Jean Dubroise to Hell in the flying canoe.

However, despite the flying canoe appearing in other stories, it was the legend of La-chasse galerie that went on to become one of the most popular in New France. Indeed, even following the British Conquest of 1760, La-chasse galerie would still remain a staple folktale among the population. A new class of fur traders called the voyageurs formed and they kept the story alive on their long voyages to the far reaches of the wilderness.

The most popular version of La-chasse galerie was written by one-time Montreal Mayor Honoré Beaugrand, a bilingual politician, journalist, author and folklorist.

Elected in 1885, he governed the city through a devastating smallpox crisis. After serving for two years, he was defeated in the following election by a man name John Abbott.

Not to be discouraged, Honoré Beaugrand returned to focus on his writing. In 1892, he published La-chasse galerie in English (with several French words thrown in for good measure) in Century Magazine.

According to the magazine: “The writer has met many an old voyageur who affirmed most positively that he had seen bark canoes traveling in midair, full of men paddling and singing away, under the protection of Beelzebub, on their way from the timber camps of the Ottawa to pay a flying visit to their sweethearts at home.”

With the story still fresh on Beaugrand’s mind, in 1900, he published Légendes canadiennes in French, a series of legends which included La Chasse-galerie, with illustrations by Henri Julien. In Beaugrand’s version, Montreal is at the geographic center of the story and plays a major role in the build-up to the climax. The legends can be read here in English.

Beaugrand’s version begins at the Ross lumber camp in the Gatineau region, where a group of miserable lumberjacks are spending New Year’s Eve, 1858, in a distant forest.

Joe, the cook, narrates a story from his youth to his fellow shantymen. He explains that about 35 years before, the camp’s second boss, Baptiste Durand, made a deal with the Devil in order to be able to visit his sweetheart in the far-away village of Lavaltrie, via a flying canoe, no less!

Joe explains that Baptiste, who had not been to church in seven years, was the architect of the unholy plan:

“We can go to Lavaltrie and back in six hours. Don’t you know that with la chasse-galerie we can travel 150 miles an hour, when one can handle the paddles as well as we do. All there is to it is that we must not pronounce le nom du bon Dieu (the name of God) during the voyage, and that we must be careful not to touch the crosses on steeples when we travel.”

He surmises that they will be safe so long as they look where they are going, think about what they say before opening their mouths and avoid drinking any alcohol.

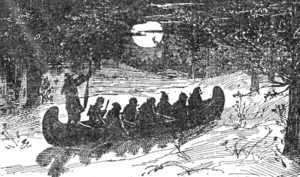

Despite some apprehension, seven of the lumberjacks, including Joe, decide to join Baptiste on the voyage. In order to overcome the 300 mile distance, the Devil provides a large, flying canoe.

While Beaugrand’s version offers little in the way of a description of the canoe, other folklorists do. In S.E. Schlosser’s “The Flying Canoe” (Spooky Canada, pages 96 – 103), the canoe “was decorated from top to bottom with archaic symbols in a red dye that looked as if it might be human blood.”

Furthermore, on dark nights “the symbols glowed, casting evil red shadows among the trees. And strangest of all, the canoe seemed to whisper to itself in a strange tongue that sounded like the hiss of snakes.”

In any case, the men climb aboard the strange vessel and pronounce the following magic words: “Acabris, Acabras, Acabram! Fais nous voyager par-dessus les montagnes!”

Suddenly, the canoe shoots up into the air to a height of five or six hundred feet and begins flying over the wintry forest until they reach the Ottawa River. En route to Montreal, the canoe whips past the church steeples dotting the villages along the river, which Beaugrand compares to the bayonets of marching soldiers on Montreal’s military parade ground:

“We began passing the tin-covered steeples as quickly as telegraph-poles fly past in a railway-train, and the spires shone in the air like the bayonets of the soldiers drilling on the Champ de Mars, in Montréal.”

Flying over forests, rivers, towns, and villages, the woodsmen leave a trail of sparks in their wake. Soon they can see the dim lights of Montreal. As the canoe approaches the city, the men begin to spot numerous steeples. Montreal had a reputation for its church towers and actually was known as the “City of Spires” and “la ville aux cent clochers” (the city of a hundred belltowers).

In fact, by the time famous American author and wit Mark Twain visited Montreal in 1881, he quipped: “This is the first time I was ever in a city where you couldn’t throw a brick without breaking a church window” during a speech at the tony Windsor Hotel on December 10.

Returning to the story of La chasse-galerie, as the canoe approaches Montreal, Baptiste decides that it would be amusing to try and terrify the people still partying on the streets below in the wee hours of the morning. He says to Joe:

“Look out there; “we will just skim over Montréal and frighten some of the fellows who may be out at this hour of the night. Joe, clear your whistle and get ready to sing your best canoe-song, “Canot d’écorce,” my boy.”

With the stroke of a paddle, Baptiste brings the canoe “down on a level with the summit of the towers of Notre-Dame” and the men start singing Canot d’écorce, an old song from the days of New France about a flying canoe. Quebec folk music band Les Cailloux does a rousing version here.

As they swoop down on the city, Joe notes:

“Although it was well on toward two o’clock in the morning, we saw some groups of men who stopped in the middle of the street to watch us go by, but we went so fast that in a twinkle we had passed Montréal and its suburbs.”

They continue their voyage, whipping past the steeples of Longue Pointe, Pointe-aux-Trembles, Repentigny and St. Sulpice until they finally arrive at their destination of Lavaltrie.

The men soon learn that a dance, a New Year’s hop, is in full swing at the home of an elderly gentleman named Batissette Augé. Before joining the festivities, Baptiste warns the men one last time not to drink any rum or whiskey and to be ready to depart on his signal.

The woodsmen join their loved ones and dance and party throughout the night.

When the time comes to depart, the men reassemble outside. Unfortunately it appears as though Baptiste is drunk, having consumed all sorts of alcohol at the party, contrary to their original plan. The other lumberjacks are rightfully worried but climb aboard the canoe regardless.

Before taking off, Joe exclaims:“Look out, Baptiste, old fellow!” Steer straight for the mountain of Montréal, as soon as you can get a glimpse of it.”

“I know my business,” answers Baptiste sharply, “and you had better mind yours.”

After pronouncing the magic words, the canoe shoots off into the sky. Once airborne, it becomes apparent that Baptiste is having trouble steering the canoe in his drunken stupor. Like lightning, they fly past the steeple of Contrecoeur, almost hitting it. Instead of heading west towards Montreal, Baptiste mistakenly steers towards the Richelieu River. A few minutes later they skim over Beloeil Mountain (today’s Mont Saint Hilaire) and come within ten feet of striking the big cross that the Bishop of Quebec had planted there a few years earlier during a temperance picnic.

Joe yells: “To the right, Baptiste! Steer to the right, or else you will send us all to le diable if you keep on going that way.”

Baptiste steers instinctively to the right, straight for Mount Royal, which the men can perceive in the distance by the lights of the city. While passing over the Montreal, Baptiste utters a yell and with a flourish of his paddle over his head, sends the canoe plunging into a snow-drift into a clearing on the side of the mountain. Luckily the snow is soft, nobody is injured and the canoe is still intact.

However, Baptiste, in a drunken stupor, declares that he is going to go downtown to have another drink. The lumberjacks try reasoning with him, but to no avail. After a brief consultation, they jump Baptiste, hold him down in the snow, and bind him hand and foot to ensure he cannot escape. They place him back into the canoe and even gag him to prevent any cursing.

With a rousing “Acabris! Acabras! Acabram!” the canoe shoots into the sky again, this time with Joe steering straight for the Gatineau. As the clock ticks, the men worry that it may be too late to save their souls. They follow the Ottawa River as far as the Pointe-Gatineau, and then steer due north using the polar star to navigate towards the lumber camp.

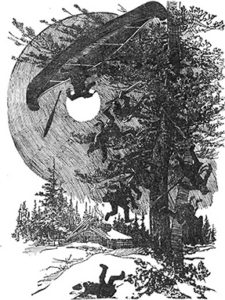

All of a sudden, Baptiste manages to free himself from the ropes and pull off the gag. He stands up, paddle in hand, and begins “swearing like a pagan”. With only a few miles to go, the men paddle furiously through the air over a pine forest. Baptiste begins swinging his paddle wildly in the air as he curses. Taken aback, Joe makes a false movement with his paddle, causing the canoe to lurch downwards towards the forest. They slam into a large pine tree and then men begin falling through the branches towards the snowy ground below. Joe is knocked unconscious during the fall.

When he wakes up at around eight o’clock the next morning, Joe is in his bunk in the cabin. Apparently his comrades had found the lumberjacks up to their necks in a snow bank at the foot of a gigantic pine tree and brought them back to camp. Having escaped the Devil, Joe concludes the tale with:

“All I can say, my friends, is that it is not so amusing as some people might think, to travel in mid-air, in the dead of winter, under the guidance of Beelzebub, running la chasse-galerie, and especially if you have un ivrogne to steer your bark canoe. Take my advice, and don’t listen to anyone who would try to rope you in for such a trip. Wait until summer before you go to see your sweethearts, for it is better to run all the rapids of the Ottawa and the St. Lawrence on a raft, than to travel in partnership with le diable himself.”

While Beaugrand’s version of the story saves the men from an eternity in Hell, many other versions are not as generous to the woodsmen. During the climax of S. E. Schlosser’s tale, for example: “The men screamed, clutching to the sides of the craft as if this would help break the fall. Then the canoe smashed into the top of a large pine tree, and the men tumbled out and fell, down towards a gaping dark hole that snapped open in the earth beneath them. It looked like the open jaws of a shark, waiting to swallow them whole. In its depths, the lumberjacks could see the raging red fires of hell. Baptiste and the other men plunged into the hole, and it snapped shut behind them with a sharp cracking sound that echoed throughout the forest. In the treetop, the broken black canoe pulsed again with a blinding red light, and then disappeared in a puff of sulfurous smoke”

In some versions of the tale the men are never seen again, whereas in others they are doomed to hurtle through the air in the canoe, en route to Hell, every New Year’s Eve.

There can be no denying that the legend of La Chasse-galerie has inspired many artistic creations, including paintings, plays, animations, films, songs and symphonies. The tale has even inspired restaurants and a craft beer!

The Chasse-galerie Restaurant, located at 4110 Saint Denis Street in Montreal, offers sophisticated French cuisine and has received decent reviews.

Meanwhile, in Lavaltrie the Café culturel de la Chasse-galerie features a fine menu along with live entertainment and cultural events.

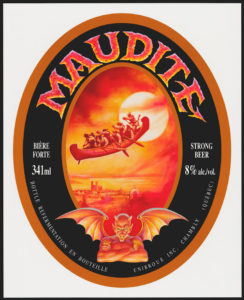

For beer lovers, a micro-brewery called Unibroue was so inspired by the story that its brewmasters created a strong craft beer called Maudite (translation: the damned) in 1992.

With a content of 8% alcohol, the label features the canoe flying past Montreal with the Devil grinning in the foreground.

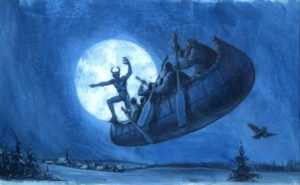

In the arts, the tale has inspired many prestigious artists to create works based on it. For example, famous Quebec illustrator and painter Henri Julien created an oil painting on canvas in 1906 called Chasse-Galerie.

The fantastic legend has also appeared in theatrical form, in the province of Ontario. Toronto’s Soulpepper Theatre produced a version of La Chasse-galerie in 2016, prompting one critic to declare in a review that it “deserves to be a new theatre holiday classic.”

La Chasse-galerie has also been made into various films. In 1996, Robert Doucet created a short animation for the National Film Board, which can be seen here.

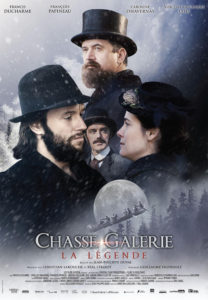

More recently, in 2016 a feature-length movie called Chasse-Galerie: La Légende was launched in French. The trailer is here.

Directed by Jean-Philippe Duval and starring Francis Ducharme, Caroline Dhavernas, François Papineau and Vincent-Guillaume Otis, it also features Montreal in several scenes.

In music, the legend appears in a spectrum ranging from folk songs to symphony orchestras. One song called Martin de la chasse galerie by Michel Rivard also situates the flying canoe over Montreal. In the lyrics, young women frequenting Saint Denis Street are implored to look up if they hear a noise in the sky to witness the damned canoe flying past.

Not to be outdone, the Montreal Symphony Orchestra produced Le diable en canot d’écorce : un conte de Noël de Michel Tremblay in December, 2017. The audience was treated to the storytelling skills of popular actor Laurent Paquin as maestro Kent Nagano conducted the orchestra throughout the tale. Written by Montreal’s most famous playwright, Michel Tremblay, the performance took place beneath a suspended birchbark canoe with wings made from wooden paddles.

Furthermore, in Tremblay’s version Montreal stars as the location of the party that the lumberjacks visit.

With so many versions of the legend crossing so many artistic mediums, La Chasse-galerie is certainly the most popular folk story in both Montreal and Quebec. Rooted in the era of New France, this cautionary tale continues to inspire people to this very day and will likely continue to do so long into the future.

For those celebrating New Year’s Eve in Montreal, the legend has it that if a person hears a noise from the sky, they should look upwards. The odds are that they might just witness a flying canoe full of screaming, terrified lumberjacks whipping past them on their perilous journey to Hell.

COMPANY NEWS

Haunted Montreal is currently in winter mode, meaning there will be no more public ghost tours until May, 2018. Private tours are still available for groups of 10 or more people, subject to the availability of our actors and weather conditions.

Haunted Montreal has been doing extensive research into potential winter activities, such as haunted pub crawls. After visiting Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia, Haunted Montreal researchers are now distilling the information gathered in hopes of creating some winter activities in Montreal.

We may offer a prototype in early 2018 and are planning a full season of activities the following winter.

A big thank you to all of our clients who attended a Haunted Montreal ghost walk during the 2017 season! If you enjoyed the experience, we encourage you to write a review on our Tripadvisor page, something that helps Haunted Montreal to market its tours. Lastly, if you would like to receive the Haunted Montreal Blog on the 13th of every month, please sign up to our mailing list.

Coming up on February 13th: The Old Royal Victoria Hospital

At the eastern base of Mount Royal sits the abandoned Royal Victoria Hospital, a dark, creepy and imposing structure. Built in 1893 in the Scottish baronial style, the hospital operated for well over a century before finally being shuttered and relocated in 2015. Some say that the old buildings had simply become too haunted for patients to recover peacefully. Ghostly invalids from the 1800s would wander the hallways, buzzers inexplicably summoned nurses to empty rooms, strange light anomalies startled people and orbs sometimes floated about. It is said that the dead passed away there, but they just did not move on. Some patients had difficulty recovering, including one woman who woke up to a mysterious pool of blood in her bed that was soaking her into her pajamas! When the hospital began reporting the ghost stories on its own website, plans were made to relocate to a shiny new super-hospital in N.D.G. Now that the buildings are abandoned, they are spookier than ever. Nobody knows what the future holds for the Old Royal Vic, but whoever inherits these buildings will also inherit their haunted legacy!

Donovan King is a historian, teacher, tour guide and professional actor. As the founder of Haunted Montreal, he combines his skills to create the best possible Montreal ghost stories, in both writing and theatrical performance. King holds a DEC (Professional Theatre Acting, John Abbot College), BFA (Drama-in-Education, Concordia), B.Ed (History and English Teaching, McGill), MFA (Theatre Studies, University of Calgary) and ACS (Montreal Tourist Guide, Institut de tourisme et d’hôtellerie du Québec).

This Post Has 0 Comments